Reading time: 12 minutes

In November 1944, the Allied campaign to liberate Italy was already well into its second year. Months of fighting on the peninsula had pushed the Germans back to the Gothic Line, a defensive network stretching from the Ligurian Sea to the Adriatic. Arrayed against this final obstacle were troops from nearly three dozen Allied nationalities, including Americans, Britons, Indians, Greeks, South Africans, Canadians, New Zealanders, and Gurkhas from Nepal.

By Morgan WR Dunn

But among these was one of the most unusual forces ever to join the fighting in Europe: the 25,000 Brazilian soldiers and pilots of the Brazilian Expeditionary Force. An idea born out of political necessity, the “Smoking Snakes” played a brief, important, and fascinating role in the fighting in Europe.

BRAZIL GOES TO WAR

When Germany invaded Poland in 1939, nobody, including its president, Getúlio Vargas, expected Brazil to play a major role in the new European war. Vast but sparsely populated, fabulously wealthy in resources but economically underdeveloped, 1930s Brazil possessed an uncomfortably old-fashioned military, an active community of Axis sympathizers, and an aggressive rival in Argentina.

But Vargas was determined to transform his country into a unified regional power, and after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor in 1941, one of U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt’s first priorities was to ensure the United States’ neighbors were on his side. After the Rio Conference in January 1942, Vargas finally decided that “Brazil must now stand or fall with the United States.”

Brazil would offer its resources, land for bases to control the South Atlantic, and eventually, a combat force to carry the fight to Europe. The first two were welcome to the United States. The third was less attractive, but it would come – if only Brazil could navigate major obstacles on the path to war.

Washington had hoped, with the Rio Conference, to get all eight South American republics to sever relations with the Axis powers. In the end, only Brazil did so, and even if it had had its neighbors’ support, the decision was fraught with peril. “The breaking of relations with Germany, Italy, and Japan will lead to war,” said Minister of War Eurico Gaspar Dutra, “and the Brazilian army is not ready for war.”

GERMANY’S FINAL INSULT

Dutra’s sympathies, Washington rightly suspected, lay with Germany, but he was right. The Brazilian Army had seen little fighting since the Paraguayan War of 1864-70. A French military mission had worked to train Brazilian troops in modern warfare, but these lessons were 20 years out of date by 1939 and Brazilian officers had been poor students.

Equipment would be the major sticking point in the Brazilian-US alliance. The Brazilian Army sported a motley collection of American, German, Czech, French, and Italian weapons and vehicles. Its air force, created in 1941 by combining the air arms of the navy and army, flew nearly 500 aging biplanes and light transports.

This explains Vargas’ one consistent demand: if the U.S. wanted Brazilian goods and Brazilian bases, it would have to supply American weapons for Brazilian soldiers.

American industry had surged into overdrive with its entry into the war. But Roosevelt’s war production was overstretched already, and U.S. military leaders hesitated to share weapons with an untested ally. While the two nations bickered over the issue, Vargas refused to issue a formal declaration of war. Yet Brazil’s quasi-neutrality would come to a sudden end in the summer of 1942.

Earlier that year, Kriegsmarine u-boats sank several Brazilian merchant vessels off the East Coast of the United States. Then, in June, Hitler decided Brazil’s pro-U.S. stance constituted an act of war, and launched a “submarine blitz” in retaliation. In August alone, a single long-range submarine, U-507, sank six Brazilian ships over just two days.

After what American newspapers termed “Brazil’s Pearl Harbor, the country was alive with fury. Suddenly, Vargas faced a deafening demand from his people: revenge.

BRAZIL IN ITALY

For over a year, the Brazilian Army slowly gathered sufficient numbers of men to fill the ranks of the Brazilian Expeditionary Force (Força Expedicionária Brasileira, or FEB). The new force, it was agreed with the United States, would be led by General João Batista Mascarenhas de Morais — at 61 years old, the oldest Allied divisional commander in Europe — and organized to American military standards.

But it took so long to recruit, organize, train, and negotiate its deployment overseas that Brazilians began to joke that the FEB would go to fight “a cobra vai fumar” — literally, “when snakes smoke,” or in English, “when pigs fly.”

With its antique equipment, untested reserve officers, and half-learned and out-of-date French military doctrine, the FEB was distinctly unappealing to American officers. They hoped to find a quiet pacified sector to stash the Brazilian latecomers.

But President Vargas, hoping to burnish his credentials for the postwar order to come, had secured a promise that his men would be involved in combat operations. So at last, when the first contingent of troops left Rio de Janeiro just after the D-Day landings in 1944, they wore a unique patch on their shoulders: a green snake smoking a pipe.

On Sunday, July 16, 1944, the first detachment of 5,000 Brazilian troops reached Naples. Brazilian leaders had envisioned sending an army of 100,000 to participate in Operation Torch. But the North African campaign ended before they could get there, and the force was scaled down to a single large infantry division, the 1st Expeditionary Division (1st DIE), and an air detachment.

American war planners had at last found a quiet spot to stow the Brazilian token force — or so they thought. Fascist Italy had largely collapsed the year before, leaving the Germans to occupy the northern part of the peninsula. Here, it was thought, the FEB could be kept out of the way.

JOINING THE FIGHT

Allied forces had failed to dislodge the Germans during the summer of 1944, which meant the Brazilians arrived in the thick of some of the fiercest fighting yet to be seen. After hasty retraining to bring them up to U.S. standards, the Smoking Snakes, now finally outfitted with American weapons, uniforms, vehicles, and radios, were thrown into the Gothic Line, the vast web of vicious Axis defenses strung across Italy.

This wasn’t the only surprise, either: in training, the Brazilians had failed to impress the U.S. Army. But once they reached the front, the newcomers, nicknamed “febianos” or “pracinhas,” proved to be brave and effective soldiers.

Brazilians quickly adapted to the Italian front as they worked to knock battle-hardened German defenders off of hilltops bristling with weapons. The Americans “encountered no special difficulty in incorporating the Brazilian troops other than that imposed by the scarcity of personnel capable of speaking Portuguese.”

THE BATTLE OF MONTE CASTELLO

The FEB was only in combat zones for about nine months, most of which was spent in small assaults and routine patrols. But one experience of truly fierce fighting has since taken on immense symbolic importance for Brazil’s WWII legacy. This was Monte Castello, a large hill on the boundary between the regions of Tuscany and Emilia-Romagna.

Brazilian troops attacked this hill four times in November and December, 1944. After the December assault, one German officer remarked to a captured FEB lieutenant, “Frankly, you Brazilians are either crazy or very brave. I never saw anyone advance against machine-guns and well-defended positions with such disregard for life …. You are devils.”

The final assault, Operation Encore, would take place on 21 February, 1945. As the battle unfolded, the Brazilians displayed surprising efficiency and tenacity, with casualties of over 400 – ten times that of the Germans. The success at Monte Castello was greeted with rapturous applause in Brazil. An editorial in the newspaper Correio da Manhã boasted that:

“The young Brazilians who implanted the Brazilian banner on [Monte Castello’s] summit will conquer for Brazil the place that it merits in the world of tomorrow.”

Despite its symbolism, Monte Castello was not the FEB’s most impressive feat of arms. That would only come in April, when the 1st DIE was ordered to liberate the town of Montese from the German 148th Division and three Fascist Italian divisions.

Over the course of four days of heavy fighting, the Brazilians suffered similar casualties to those at Monte Castello. But the rewards were much greater: two generals, 800 officers, and 14,700 Axis soldiers were captured. The 148th was the only intact German division to surrender on the Italian front, and it was the first to do so. During 229 days in combat, the Brazilians had proven themselves to allies and enemies alike.

THE FORGOTTEN LEGACY OF THE FEB

The Brazilian Expeditionary Force had evolved from an impractical reality into a battle-tested army equal to its Allied counterparts. General Mark W. Clark, under whose Fifth Army the FEB had served, recalled that “it was pleasing to observe the way in which the BEF progressed in the final stages of the campaign. They never complained and always were anxious to carry their share of our burdens.”

For Allied forces in Europe, the next great task was occupation. The Allies would occupy Germany, Austria, and Japan, and parts of Italy for years after the war as political leaders sought to restore order and prosperity. Brazil, if it wanted, could play a part.

Before they’d reached Italy, U.S. officers had doubted the FEB’s abilities. Now it was the Brazilians’ own officers who underestimated them. General Mascarenhas believed his men looked less impressive and weren’t skilful or disciplined enough for occupation duties, and others believed it would cost the Brazilian treasury too dearly.

It’s likely that contributing to the occupation would have yielded significant benefits for Vargas’ regime, but it wasn’t to be. Orders were issued for the immediate return of the FEB upon the conclusion of hostilities.

“We did not know how to take advantage of what we had done,” diplomat Vasco Leitão da Cunha later wrote. “We got stuck in intrigues, lesser things, when we had a natural ally. We strayed out of step with the United States.” Still, its active participation in the European war meant that “Brazil stopped being an adolescent country and became a serious country.”

Upon their return, conscripted and volunteer pracinhas were discharged, and regular soldiers returned to their regiments across the country. Over the objections of those who’d hoped that the FEB would form the core of a new, modernized Brazilian Army which could act as a stabilizing force in South America, Vargas chose to forfeit the valuable experience these men had accrued.

In the postwar years, the veterans of the Brazilian Expeditionary Force would form associations and museums, most of which have faded with time. While the FEB was only a small portion of the Allied armies, it nevertheless holds an honored place in the history of the Second World War as the only Latin American force to travel beyond its borders in the fight to extinguish the nightmare of fascism in Europe.

Podcast Episodes about the Brazilian Expeditionary Force

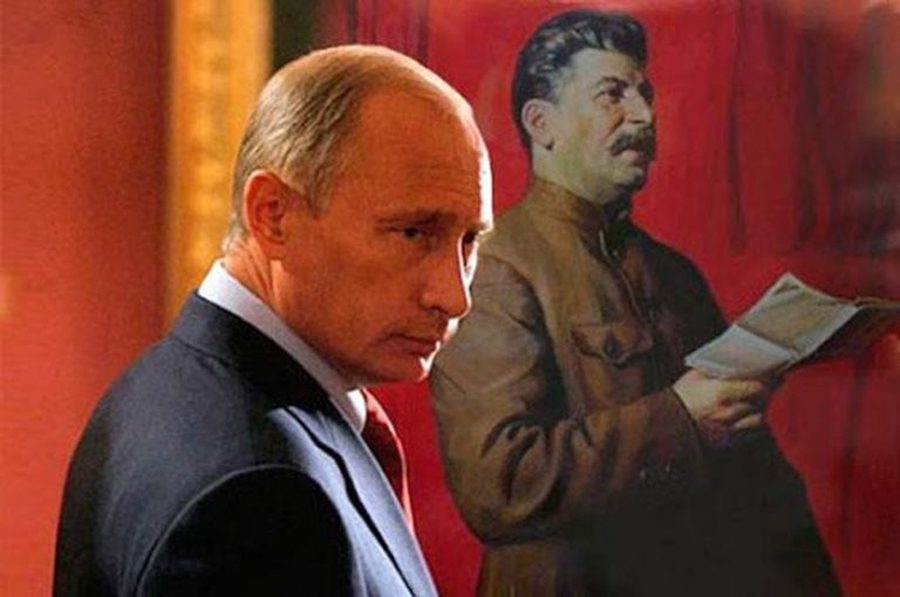

PUTIN’S PAST: The Return of Ideological History and the Strongman

Reading time: 8 minutes

From Russian Constitutional Court chairman Valery Zorkin, to former Russian culture minister Vladimir Medinsky, to presidential adviser Yuri Kovlachuk, amateur history is everywhere in the Russian government today. This is not an accident but a deliberate way to build official state ideology in Russia. For instance, in a recent interview discussing Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the deputy secretary of the Russian Security Council, Oleg Khramov, said that the West is trying “to stop the course of history” by “blinding” many Ukrainians to the historical truth of their shared civilizational identity with Russia.

The Antarctic Treaty is turning 60 years old. In a changed world, is it still fit for purpose?

The 1959 Antarctic Treaty celebrates its 60th anniversary this week. Negotiated during the middle of the Cold War by 12 countries with Antarctic interests, it remains the only example of a single treaty that governs a whole continent. It is also the foundation of a rules-based international order for a continent without a permanent population. The treaty […]

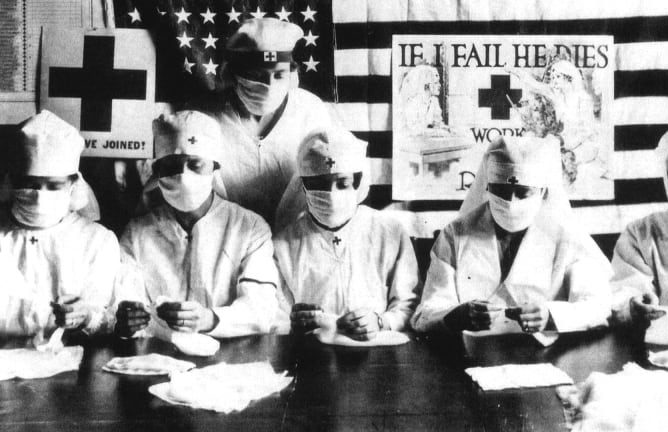

“The Flu”: A Brief History of Influenza in U. S. America, Europe, Hawaii

“THE FLU”: A BRIEF HISTORY OF INFLUENZA IN U. S. AMERICA, EUROPE, HAWAII By A. Mouritz (1861 – 1943) PREFACE This Booklet has been written and compiled for the use of any student or layman who seeks concise and clear information on the history of Influenza. Brief and salient facts are set forth relating to “Flu” […]

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.