Reading time: 11 minutes

On 31st July 1914, just days before the catastrophe of war was allowed to come to Europe, Australian Prime Minister Andrew Fisher made a solemn promise on behalf of his country to “stand beside the mother country to help and defend her to our last man and our last shilling.”

By Morgan WR Dunn

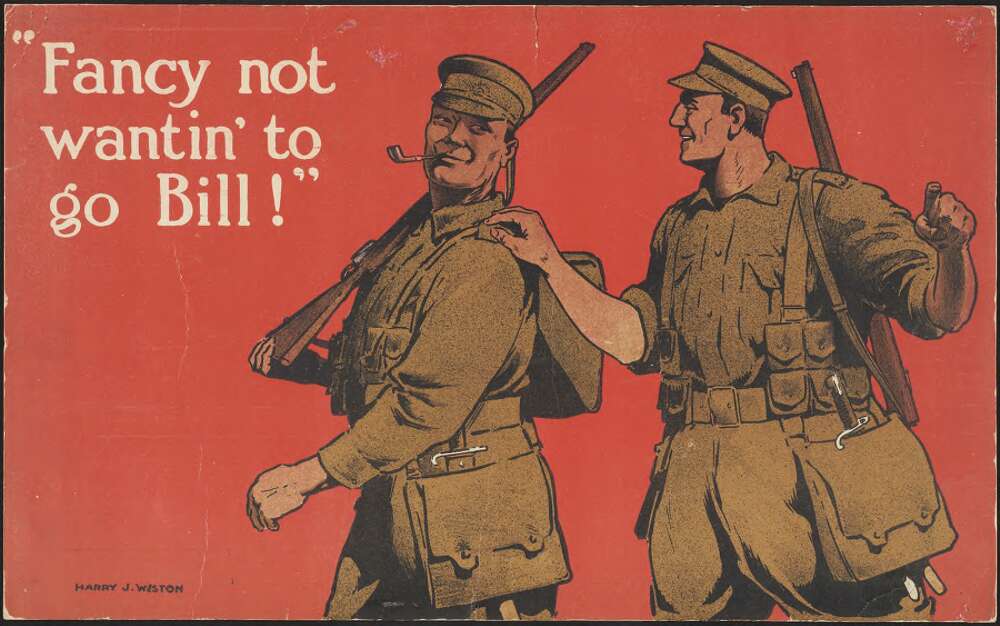

That summer the whole country was enthusiastic about the prospect. Thousands of Australian men were eager to prove their young country’s worth on the battlefields of Europe and enlisted in droves to help build the Australian Army essentially from scratch.

But as the months passed as the fighting ground on, and as stories of the horrors endured in Turkey and France trickled back to the home front, Australia’s young democracy faced one of its most harrowing trials yet as those on both sides of the issue battled to determine the path ahead.

AUSTRALIA: 1914

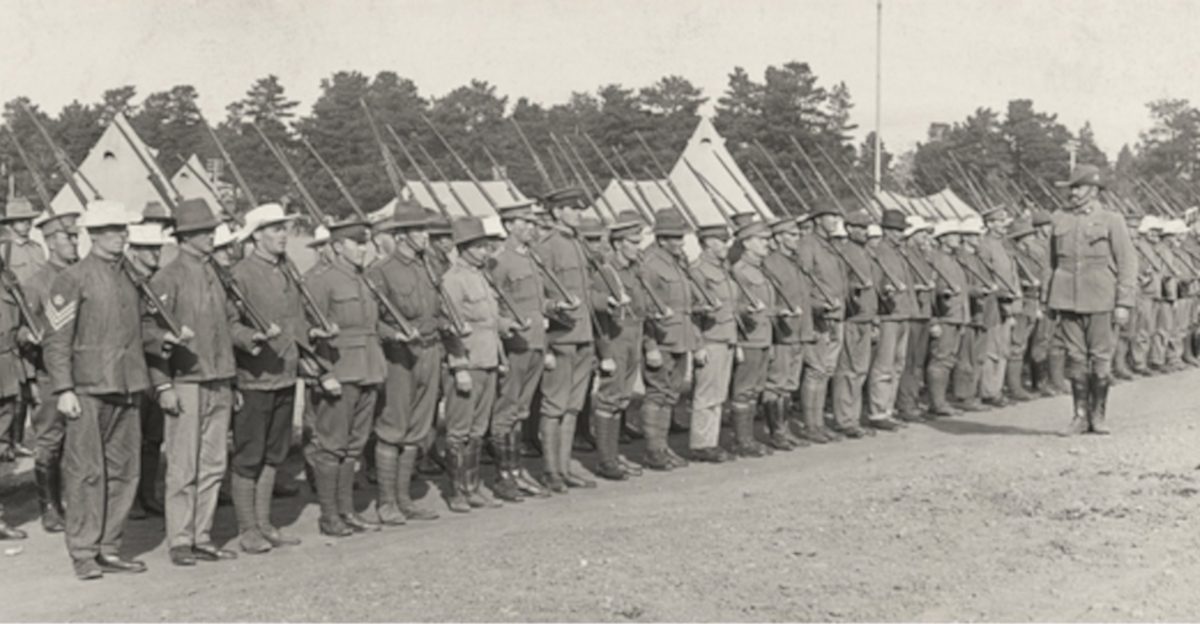

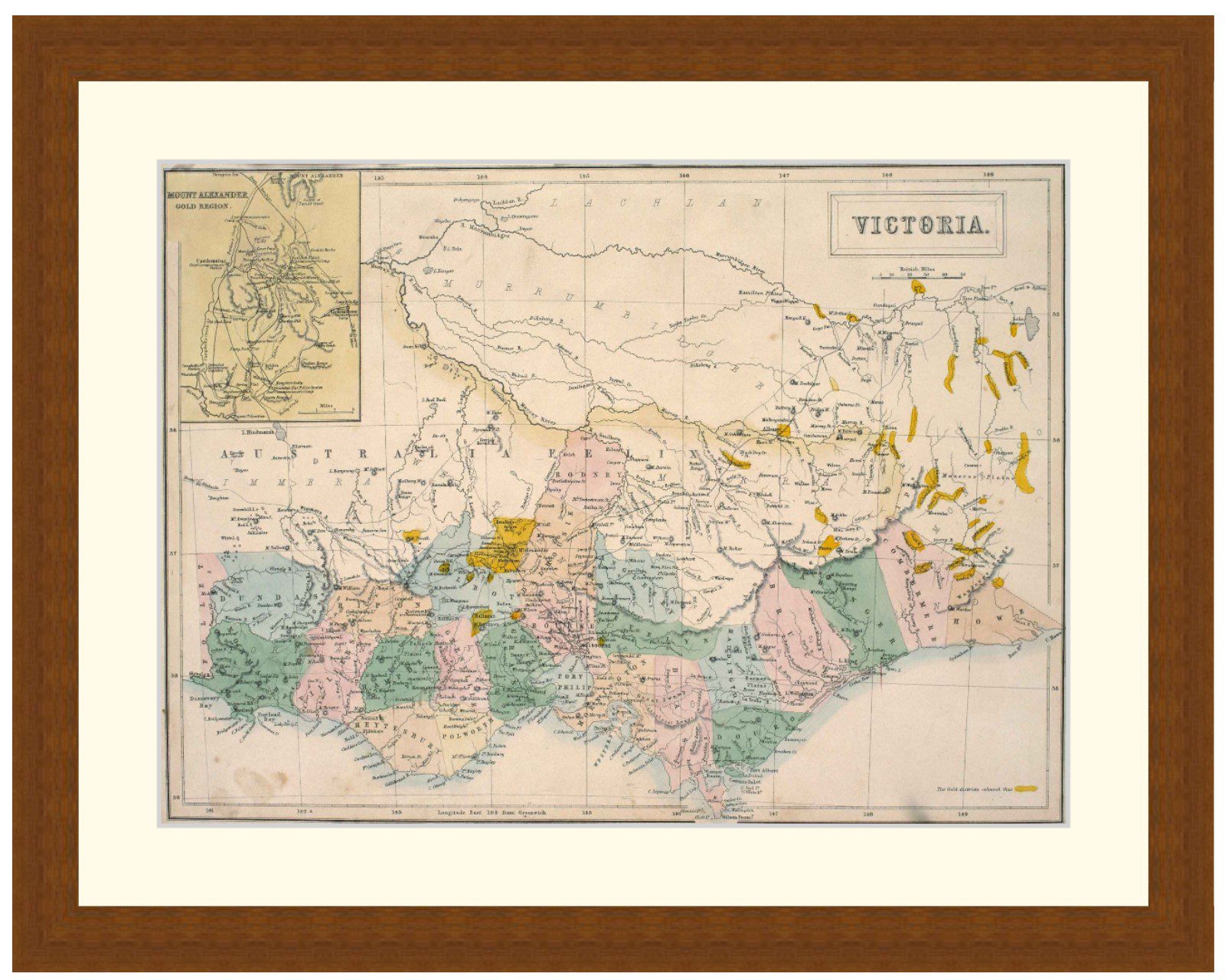

In the summer of 1914, the Australian nation was just over a decade old and home to nearly four and a half million people. At Federation, the new Australian government inherited colonial forces made up largely of militiamen. The Universal Service Scheme, a system of compulsory military training, required males from ages 12 to 26 to undergo some form of training.

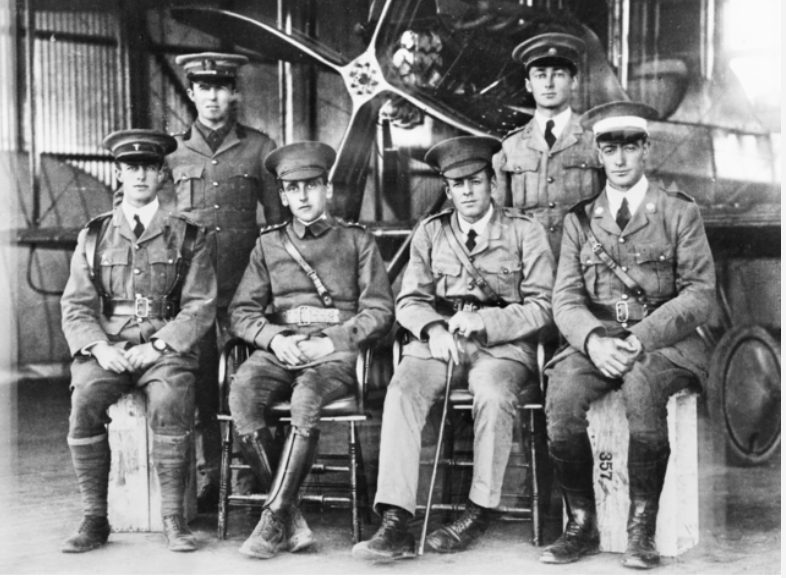

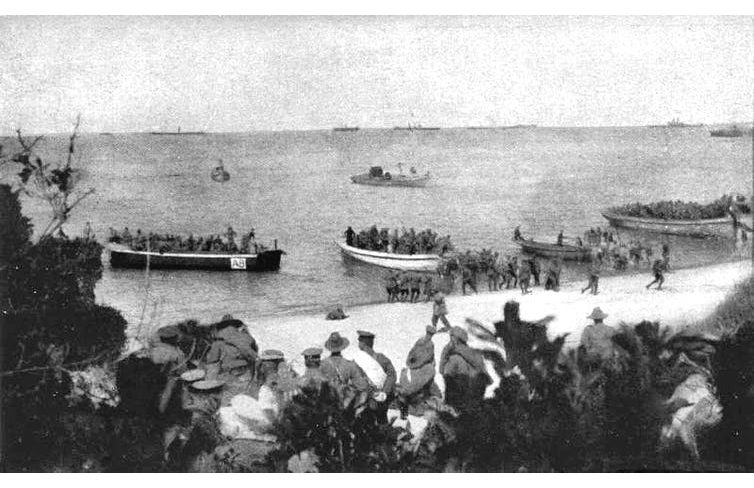

So when, as a Dominion of the Empire, Australia was automatically at war alongside Britain, the country could call upon large numbers of men ready for service. Australia’s contribution to the Empire, the Australian Imperial Force, was originally planned to number just 20,000; by the end of the year, enthusiasm was so high that over 50,000 had been accepted.

“As one historian put it,” “Australians hailed England’s declaration of war on Germany with the most complete and enthusiastic harmony in their history.’ When the recruiting offices opened on 1st August a mass of men jostled for position, and by nightfall 3,600 had enlisted in Sydney alone. Within two weeks 10,000 more had applied.”

FERVOUR MEETS REALITY

The Australian Army in 1914 could count on widespread patriotism and romantic notions of war to spur young men to enlist. But the initial fury, and several actions taken by the Australian government to illegalize anti-war speech, such as imposing press censorship, concealed less committed feelings:

“Between the fervent British-Australian loyalists. . .and the dedicated opponents of the war … the majority of Australians remained, much quieter and more confused, less certain … the bravado of many was seriously tempered by regret, anxiety and bewilderment.”

There were other incentives for many men, particularly rural Australians, to enlist: the continent was in the throes of a record-breaking droughts which would last until 1916, leaving many without work. Bored, broke, inflamed with imperial patriotism, and eager to see the world, they signed up in droves.

This innocent brashness was all but snuffed out by the reality of war. The drawn-out campaign in Mesopotamia and the savage failure at Gallipoli, where over 8,000 lost their lives, was a wake-up call: there would be no easy victory, and the volunteers, without large numbers of reinforcements, suffered extremely high casualty rates, with some soldiers wounded as many as seven times.

Conditions had worsened on the home front, too. The disruption of trade, German submarine warfare, the loss of working men, wartime price controls, and censorship had driven up unemployment, the cost of living, and paranoia. Prime Minister Billy Hughes, who’d succeeded Fisher in October 1915, suppressed knowledge of real casualty rates and conditions at the front, but he couldn’t conceal the truth forever.

As enlistment rates dropped from 1916 onwards, particularly following the gruesome outcome of the Battle of the Somme, Australia’s divisions, now relocated to the Western Front, were growing weaker, the men exhausted. Hughes, visiting Britain, feared that unless he could get the divisions back up to strength, they would have to be disbanded, their component units redistributed to British formations. When he returned, he raised an issue he’d hoped – and promised – he’d never have to resort to.

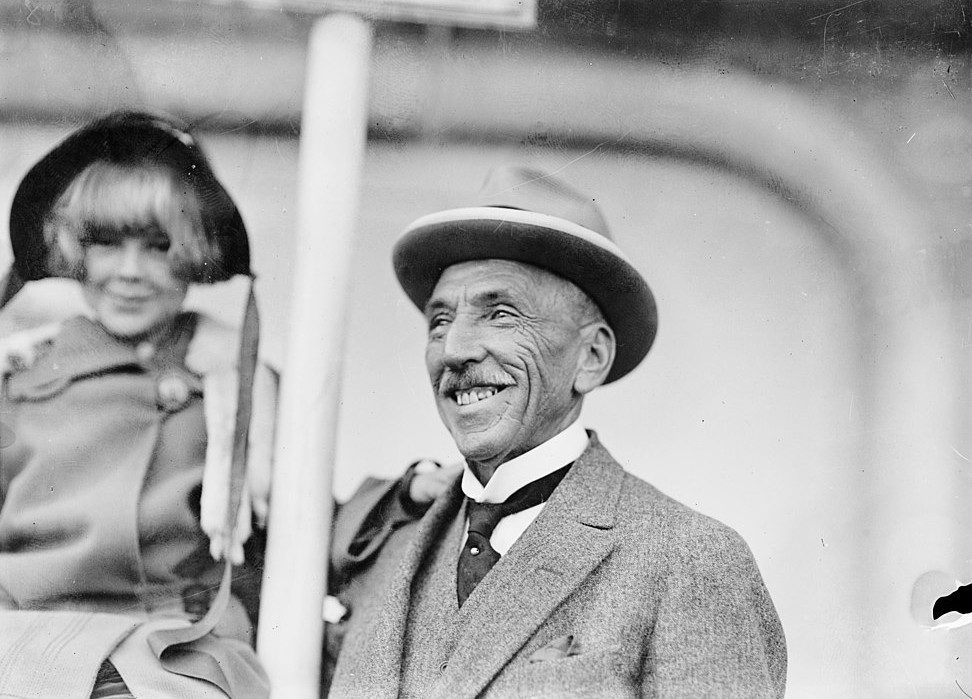

BILLY BRINGS THE ANSWER

Hughes was a contradictory, combative, and colourful politician who’d begun his career as a socialist trade union organiser. When war broke out, both the Commonwealth Liberal and Hughes’ Labor Parties had fallen in step with the Empire.

The Australian political establishment understood that conscription was deeply unpopular. While the Universal Service Scheme required males to undergo military training, it did not give the government power to send Australians abroad for military service without their consent. Even in 1915, in the House of Representatives, Hughes claimed that “In no circumstances would I agree to send men out of this country to fight against their will.”

But 1916 was another matter. The British War Council had placed Hughes under intense pressure to supply 5,500 recruits per month to keep the Australian forces at fighting strength. By the time he returned on 31st July 1916, he’d concluded that conscription was the only solution.

He faced several problems on his return to Australia. For one, his own Labor Party was deeply divided over the issue, as was the Australian population, including working-class Irish Australians who suspected they would bear the brunt of service. Many Australians also worried that, to keep the economy running, the government would import large numbers of “black” immigrant labourers to take the places of conscripted men. At the same time, Hughes had staked his political future on making a strong Australian contribution to the war effort as a demonstration of the country’s significance on the international stage.

Rather than turn to his own party for support or make use of an extraordinary power which allowed him to conscript by executive order, he chose a more democratic option: on 28th October 1916, Australians would hold a referendum (technically a plebiscite) to decide the matter.

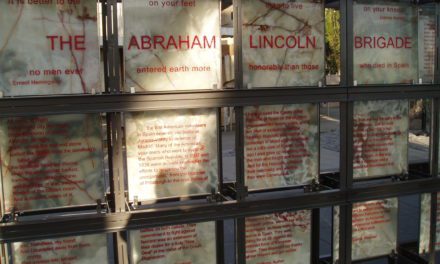

THE FIRST REFERENDUM

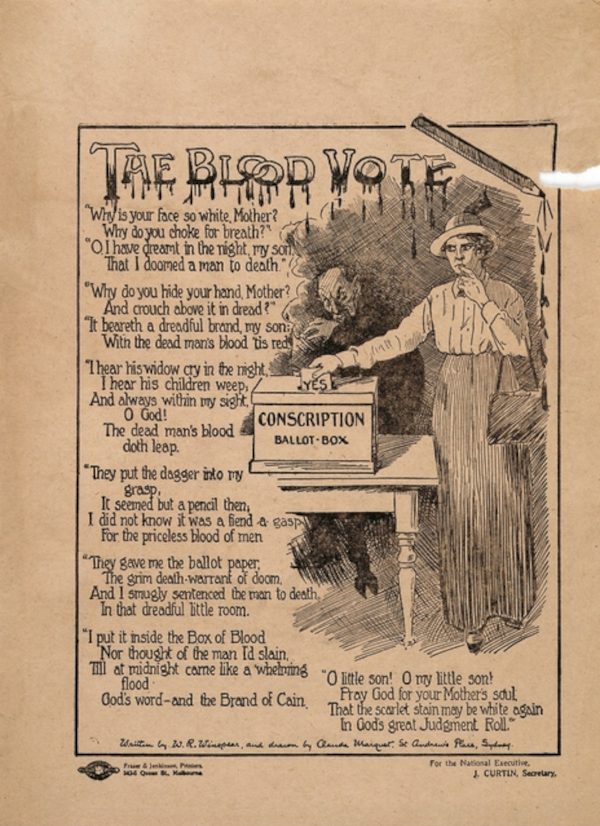

The months leading up to the vote were marked by a near-breakdown in civil order. Mass demonstrations and rallies were held by those both for and against conscription, many of which turned violent and took on a nativist bent. Australian women, who’d held the right to vote since 1894, were under particular pressure. The pro-conscription camp called on women to think of other mothers, sisters, and wives whose men were struggling at the front. The opposition inverted the argument, urging women to protect their male relatives from danger.

Significant cultural figures like Daniel Mannix, Catholic Archbishop of Melbourne, took a public stance against conscription, calling it “a hateful thing… almost certain to bring evil in its train.” So did many at the federal and state levels within the Labor Party; Labor MP Frank Anstey pointedly asked “what is the good of victory abroad if it only gives us slavery at home?”

Hughes didn’t help matters. Confident he would succeed, he issued a general call-up of men for the militia, which was seen as a prelude toward compulsory overseas service. What’s more, he threatened to conscript men who’d failed to answer the call-up when they appeared to vote, and passed a preemptive resolution ratifying conscription.

These facts, along with the resignations of several government ministers, became public knowledge despite Hughes’ attempts to cover them up. And when he branded the anti-conscriptionists as being made up of “every enemy of Britain open and secret in our midst,” including “the violent and the lawless, the criminals who would wreck society and ruin prosperity,” he drove undecided voters firmly into the “no” camp.

When they went to the voting stations, Australians were asked to answer “yes” or “no” to the question:

Are you in favour of the Government having, in this grave emergency, the same compulsory powers over citizens in regard to requiring their military service, for the term of this war, outside the Commonwealth, as it now has in regard to military service within the Commonwealth?

When the count came in, 48.39% had voted yes, 51.61% no – a paper-thin margin of 3.2%. The soldiers themselves, nearly 300,000 in number, voted in favor by a mere 12,000, another crushing blow for Hughes, who’d hoped to bolster public support with a show of military enthusiasm. In 1916, at least, no Australian would be forced into uniform – but the war still raged, and the conscription question was still unanswered.

THE SECOND REFERENDUM

The outcome of the 1916 referendum was a disaster for Hughes. A convention of Labor Party delegates from each of the states voted 29-4 to expel pro-conscription Labor leaders. Hughes’ faction formed the Nationalist Party with backing from the Liberals.

Surprisingly, Hughes’ Nationalists won a comfortable victory in the May 1917 general election. Encouraged, he announced that there would be a second referendum in December of that year.

On the Western Front, meanwhile, the situation had only grown more dire. “By the end of 1917,” wrote historian Jeffrey Gray, “the allies were facing severe manpower shortages.” While the arrival of the American Expeditionary Force that year alleviated the pressure, every other allied nation had adopted conscription. Australia alone had not, save for South Africa and India, where fragile colonial elites chose not to risk widespread rebellion over the issue.

In 1917, Hughes was even more fiercely determined than before to succeed. “October 28th, 1916,” he said on 12th November in Bendigo, “was a black day for Australia… a triumph for the unworthy, the selfish, and anti-British in our midst.” All the stops were pulled out: registration was closed two days after the second referendum was announced, cutting out Australians too far from towns to hear the news in time, and anyone born in, or born to a native of, an “enemy” country would be barred.

It didn’t work. When the votes were tallied on 20th December 1917, the “no” camp won again, this time with a margin of 7.58%.

AFTERMATH

Astonishingly, Hughes’ Nationalist Party not only retained power, but would go on to win general elections in 1919 and 1922, when he was forced to step aside for Stanley Bruce. His offered resignation was turned down, and his tenure as Prime Minister would be one of the longest in Australian history.

The Australian Imperial Force, meanwhile, was kept in the line throughout 1918, despite many battalions falling to less than 50% of their authorized strength. Recruiting dropped to around 2,500 per month that year, the end of a long downward trend. The last Australian combat would take place on 5th October 1918, when 6th Brigade AIF occupied the village of Montbrehain, taking 400 German prisoners and suffering 430 casualties. After that, the AIF was withdrawn from the front line for sorely-needed recuperation; when the armistice came, they were at last out of harm’s way.

Hughes insisted that, unlike the Canadians and New Zealanders, Australian troops take no part in the occupation of Germany. They would all be repatriated within a year.

The Labor Party wouldn’t win another majority until 1943; ironically, they introduced a form of conscription to contribute to the fight against Japan. Australian conscripts wouldn’t be sent overseas again until 1966, during the Vietnam War. When Labor leader Gough Whitlam took office in 1972, this too was ended. Australia has not reintroduced conscription since.

Articles you may also like

General History Quiz 76

History Guild General History Quiz 76See how your history knowledge stacks up. Want to know more about any of the questions? Once you’ve finished the quiz click here to learn more. Have an idea for a question? Suggest it here and we’ll include it in a future quiz! The stories behind the questions 1. What […]

General History Quiz 175

1. How long has Rome been continuously occupied?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.