Reading time: 6 minutes

For the last 1,000 years and until very recently, scholars have held that the Indian sub-continent was under ‘Muslim rule’ between the 11th Century and end of the 90 year British Raj. That has recently been challenged by two scholars, Richard M Eaton and Naveena Naqvi who argue that the rule was culturally led rather than religiously led.

By Richard Shrubb.

The idea of ‘Muslim’ rule suggests that there was a religious core to rule over the region when the facts on the ground strongly suggest that while religion was held by kings, the vast array of belief systems that remain to this day show that there was more to the Persianate Age than a belief in Islam.

History written by the conquerors

Richard Eaton writes in his book, “India in the Persianate Age, 1000–1765“, that over the centuries Persian and British historians have concluded that there was religious rule over what is now Pakistan, India, Nepal and Bangladesh.

This simplified history sits well with Hindu nationalists such as current Prime Minister Nerendra Modi who argued that with the 200 or so years of British influence, India was subjected to ‘1200 years of slavery’. Within the nationalist vernacular this feeds the masses with division and hatred for what can be perceived as their former ‘Muslim overlords’. What if history wasn’t so simple?

Regionality

In a YouTube discussion about the transition from the Mughals to British rule, Naqvi suggested that the thrust of her research is showing that the peoples of India feel more allegiance towards the regions they are born and brought up in than to a greater nation state such as India or Pakistan. You can see the discussion here

Many Indian political boundaries bordering on Pakistan overlapped the border drawn up in the Partition of 1947 – there has been a hot war of varying ferocity between the two countries over Kashmir practically since the British left. Listening to Naqvi, Kashmiris would therefore consider themselves more Kashmiri than Pakistani or Indian.

Naqvi and Eaton both point to the mercenary armies that resided across the subcontinent through the centuries and were used by the East India Company to tackle problems and uprisings. Eaton shows in his book how this was used by the British in World War 1 where he says that Hindus became Sikhs merely by joining a British Sikh regiment. If there is a fluidity of religion (albeit a side-step from Hinduism as opposed to a leap to Islam) could there have been a bit more than religion in control in the Persianate Age?

Cosmopolis – a cultural rule

Eaton departs from the traditional chronological political history of the rule of kings over India and suggests that the subcontinent was ruled culturally by consent rather than religiously by kings, and this may well have stemmed from before Persianate times. He uses the Ancient Greek concept of ‘Cosmopolis’ that a website devoted to the concept describes as “the “world-city” in which all individuals are related to one another, regardless of country, race, or religion.”

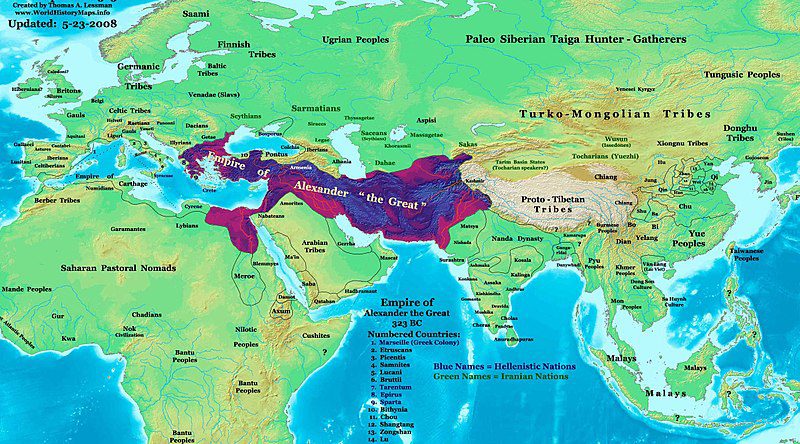

In Eaton’s view, the subcontinent was firstly, dually influenced by the East Asian cosmopolis of Sanskrit and the West Asian Persianate cosmopolis. Both languages of administration held sway over the region for many centuries but Persian would eventually win out.

Eaton has been interviewed by a range of different outlets over his decolonialised viewpoint. At the political end of the spectrum he cites two Hindu kings – Sultans Krishnadevaraya (1642-1646) and Shivaji Bhonsale (1674-1680) who both carried all the symbols of the Persianate concept of kingship yet were devout Hindus.

He shows how regionality influenced architectural vernacular, with flat roofed mosques in one region (as opposed to Muslim domes and arches) and palaces with pitched roofs in Bengal due to the monsoon’s heavy rains. These buildings didn’t sit well with the traditional argument of religious colonial rule and caused many a debate – but viewed through a cultural and regional lens sits far more comfortably.

The cultural idea runs deeper – language is core to culture. Naqvi and Eaton show the Persian language was the lingua franca of Asia and the language that was used in government administration at one point between modern-day Bosnia and modern-day India for a good 1,000 years. In his 2016 lecture Eaton argued that language was what would end up allowing Persian to overthrow Sanskrit influences over India. Why? Simply because due to the caste system, only the Brahmin caste could speak Sanskrit (even banning poetry in the language). Persian would take over from the bottom up as the language had to be learned by so many millions to communicate between regions and countries.

Watch his lecture here:

The Asian melting pot?

Today the region is known for its riot of tastes, cultures and smells that differ markedly from the southern tip of India to northern Pakistan. The Hindu caste system is problematic for many but hasn’t changed for centuries, regardless of who titularly ruled over the people. Eaton argues that while under Islam everyone is equal before God, humanity permits inequality. This is how the caste system was able to continue in the Persianate Age.

Both Naqvi and Eaton’s arguments that culture and not specifically religion was the core of the Persianate Age fly in the face of Hindu Nationalist ideology that divides the region so much today. Though a radical rethink of the history of the subcontinent this sits well on many fronts. It shows that harmony has been at heart of history for the millennium in question; and also fits better with the evidence presented by contemporary scribes and cultural artefacts of the time in question. It also shows how today the visitor to the subcontinent will see such a melting pot of cultures and languages that exist that have survived the last 1,200 years regardless of whom ruled over the region.

Podcast episodes about the Indian Persianate Age

Articles you may also like

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.