HOW THE AUSTRALIAN SECRET SERVICE HELPED OVERTHROW THE CHILEAN GOVERNMENT

Reading time: 8 minutes

Recently, documents came to light that showed that the Australian Secret Intelligence Service (ASIS) played a small but active role in the Chilean coup of 1973, when General Augusto Pinochet overthrew the elected government of President Salvador Allende. In this article History Guild takes a closer look at these documents as well as the related events.

By Fergus O’Sullivan

First, though, a little background. In 1970, Salvador Allende, a socialist, was elected to the Chilean presidency. Though he was a devout Marxist and an admirer of the Cuban revolution (he counted Fidel Castro and Che Guevara among his friends), for him revolution was achievable by democratic means, not necessarily bloody uprising.

To prove this, Allende worked to improve the Chilean’s people’s lot within the system. He nationalized many industries and redistributed land to ensure that their profits wouldn’t just remain with a small group of fat cats. He also started programs to distribute free milk to children and provide healthcare to the population.

For his trouble, Allende was vilified by the right in both Chile and abroad. In the United States his approach was seen as a threat, probably due to a combination of the belief in the domino theory — which stated that if one country “fell” to communism many others would follow — as well as the Monroe Doctrine which, in short, designated all of the Americas as the United States’ “sphere of influence”.

The American attitude to Allende is probably best put into words by Edward M. Korry, who was the U.S. ambassador to Chile from 1967 to 1971. In an interview he gave a few years before his death in 2003, he described Allende as a “slavish admirer of Castro” among other things. An excerpt of the interview is below.

Korry wasn’t alone, either. Even before the official result of the 1970 election was in, U.S. President Richard Nixon gave the order to the Central Intelligence Agency to get to work to get rid of Allende. Having a government care for all its people and not just the wealthy elite apparently was a step too far for Tricky Dicky.

The CIA in Chile

By 1970, the CIA were dab hands at overthrowing democratically elected governments — we’ll let the length of the Wikipedia article about U.S. involvement with regime change speak for itself, the Bay of Pigs notwithstanding.

The organization decided on two tried and true “tracks”. Track I would focus on building resistance against Allende in Chile’s parliament through bribery and stuffing ballot boxes. Together with trade sanctions levied by Nixon, the hope was that this would undermine the Allende government enough that the Chilean people would choose another government to lead them, one more amenable to American suggestions.

If this failed, then there was always track II, a violent overthrow of the government, to be replaced by an American puppet. Though radical, bloody and unpleasant, the CIA had few qualms about setting this track into motion simultaneously with track I, just in case.

Australia and Chile

All the above is pretty much a matter of public record: there have been Congressional hearings in the U.S., for example, that laid bare the CIA’s activities in Chile. What was also known is that the Americans weren’t the only ones trying to destabilize Chile and get rid of Allende: among the rogues’ gallery was Australia, which as early as 1974 was accused of helping the CIA with their dirty work.

However, in the years since not much except rumors have come out about exactly what ASIS was doing in Chile. This changed recently when a large batch of documents were declassified and hosted at the National Security Archive. This rare event was in no small part due to the hard work of Dr. Clinton Fernandes, a security researcher who pressed the Australian government to be more transparent about its past intelligence activities.

ASIS Documents

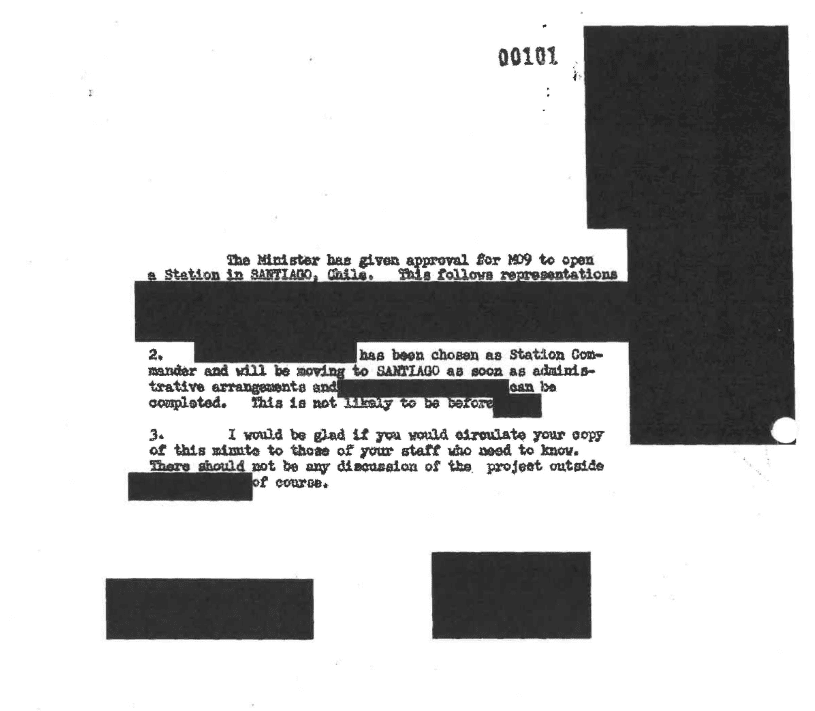

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the documents are heavily redacted, almost to the point of being unreadable. However, with some persistence, you can figure out a few things about the ASIS presence and operations in Chile.

The first memo from late 1970 mentions that a minister has “given approval” for a station to be opened in Chile’s capital, Santiago. The foreign minister at the time was the Liberal William McMahon, who harbored some anti-communist sentiments, but was no rabid red baiter, either. A few years later, when he was prime minister, he would withdraw Australia from the Vietnam quagmire.

In fact, some qualms about setting up the station popped up even before it was up and running. A few months after the initial decision, in June 1971, a memo pops up stating that somebody in the government responsible for the project was having second thoughts, considering the situation in Chile hadn’t “deteriorated” as badly as forecast. Apparently Allende wasn’t as bad as people thought.

However, in the end the station did open, as evinced by a document from December 1971, which shows that it’s up and running. There were some issues, though, notably with many of the agents not speaking Spanish well enough, and strained relations with people or organizations that have been censored. We can assume some local elements, or even the CIA, it’s a mystery.

The next document is from a year later, and seems to go over why the station wasn’t as successful as it could be. It mentions “teething problems,” issues with communicating reports and other minor matters. There’s no mention of what ASIS actually did in Chile, just that it was present and in communication with people in Santiago.

ASIS Leaves Chile

Whatever ASIS was doing in Chile, we can only assume that it played a role in the growing instability within the country. Throughout 1972 and 1973 there was sporadic violence in Santiago and the countryside, as well as strikes by the powerful elites of the country, which brought the economy to its knees. Something was brewing, and things weren’t looking good.

We can only assume that these events were what made the 1973 Labour government rethink the ASIS presence in Chile. The new prime minister, Gough Whitlam, who was also foreign minister, had second thoughts about it all as shown in the remaining documents. His main worry was for any potential embarrassment if the ASIS presence was found out and he favored shutting the station down.

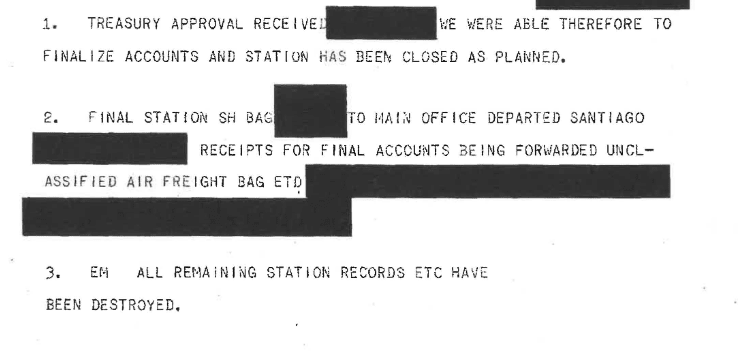

As worried as he was about what Chile and the rest of the world though, though, Whitlam seemed even more concerned about what the Americans would think: several memos go into detail on how he wanted to make clear to the Americans that he didn’t oppose their operations, just that he wanted no part in it. The station closed in July 1973, though one operative stayed behind for unknown reasons until October, a month after the coup took place.

The Coup

Whatever hand ASIS had in the CIA’s operations in Chile, one thing is for sure: they pulled out in time. Only four month after the closing message from Santiago, on September 11th 1973, tanks were rolling down Santiago’s avenues and General Pinochet took power, events we go over in our article on Pinochet’s Chile.

On hearing the news, Salvador Allende took to the radio and broadcast a moving message to his people. Shortly after, he took his own life, likely because he knew what the new regime would do to him if they captured him. With him died the only democratic Marxist revolution the world has seen.

Despite the illegitimacy of his regime, many on the right would praise Pinochet during his brutal reign, though eventually the whole thing collapsed despite his iron grip. Now, fifty years later, Chile seems to finally be on the mend from the fear and violence he reigned with. The country is writing a new constitution that will hopefully bring a new era of prosperity to the nation.

As for Australia’s role in the coup, just because ASIS pulled out early doesn’t mean its hands are clean. Not only did it leave one operative there who didn’t leave until after the butchers’ work was done, there’s no telling what it did to help the CIA set the wheels in motion. Hopefully, in the future we’ll know more about ASIS’ actions. For now, some mute black bars will have to do.

Articles you may also like

The Battle of Kadesh and the World’s First Peace Treaty

For a shining example of ancient warfare and the cause of the world’s first recorded peace treaty, look no further than the Battle of Kadesh. By Madison Moulton. The characteristics of ancient warfare are often shrouded in mystery. There is evidence of the existence of early warfare, but intricate details of battle are scarce. However, […]

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.