GENS DU PAYS: A HISTORY OF QUEBEC’S STRUGGLE FOR SOVEREIGNTY

Reading time: 13 minutes

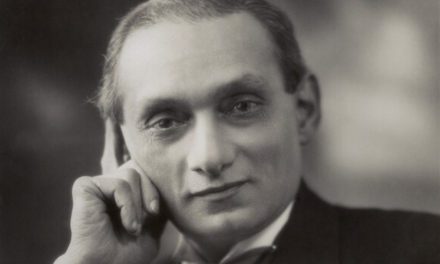

Vive le Québec libre! The date was July 24th, 1967 and with those four words French president Charles de Gaulle announced to a frenzied Montréal crowd his support for a nationalist movement with seedlings of support. By the end of his controversial speech however the movement for a “free” Quebec would no longer be small in scale; it would become a political juggernaut that became a bitter conflict between the remainder of Canada and Quebec.

By Michael Vecchio

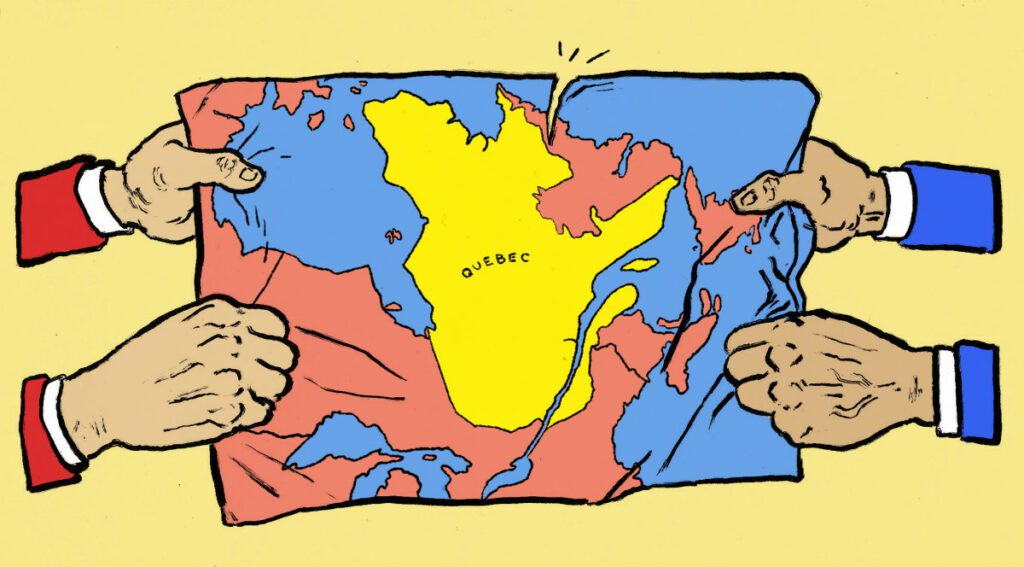

Indeed there can be little doubt that the province of Quebec is unique in not only Canada, but also in North America. It is the largest territory outside of France with a predominantly French speaking population. The province’s rich history, linguistic identity, and culture can be traced back to the French colony of New France in the sixteenth century. But despite the linguistic and cultural differences that distinguish Quebec from Canada and the other provinces, is there really a just case for a sovereign Quebecois nation?

In an attempt to assuage the situation the Government of Canada informally recognized Quebec as a distinct ‘nation’ within the Canadian Federation in 2006, yet hard line separatists maintain that the features that constitute Quebec can only be maintained, further developed and protected as an independent state. And so a political clash of wills erupted; a clash that has culminated in the emergence of radical separatists, political parties, and institutions whose raison d’être is to negotiate the independence of the province, defining much of 20th century Canadian history.

Origins of Quebec nationalism

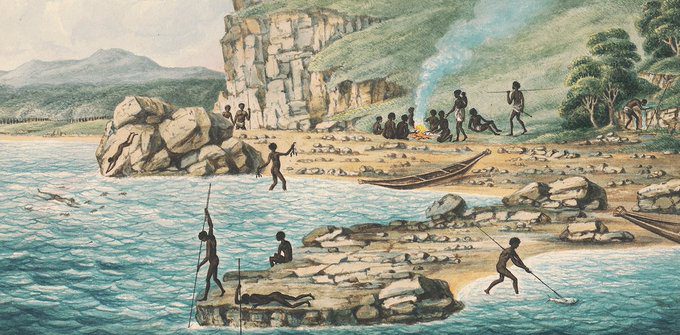

But the roots of Quebec nationalism extend as far back as 1608, when explorer Samuel De Champlain founded Quebec City, and in turn the colony of New France. The battle for supremacy on the North American continent against English colonisers culminated with the Battle of the Plains of Abraham in 1759. With a decisive victory, the British established full rule of the North American colony and the French were suddenly left with nothing to claim.

Some historians identify that the moment of losing colonial administrative rule as the earliest incidence of a nationalist movement for ‘independent’ freedom. Resentful French sentiment over British dominance was a unifier of the French population who felt they were dominated, kept dependent, cheated of equality, and threatened with loss of identity. It was with these concerns in mind, that the British allowed certain concessions to the French in the 1763 Treaty of Paris, notably the allowance of the Roman Catholic faith and certain aspects of French civil law. But these accommodations served only to satisfy briefly.

READ MORE: BATTLE OF THE PLAINS OF ABRAHAM

Throughout the American Revolution and into the 19th century as Canada achieved its Confederation from Britain in 1867, Quebec nationalism continued to simmer. Although the province would be one of four original entrants into Canada (along with Ontario, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia), sentiments of historical and cultural diversity always defined the people of Quebec, reluctant to call themselves Canadians.

The Quiet Revolution

It was not until the events of the 1960s, however that the fight for independence materialized into more than an ideological dream from centuries past, but a flesh and bone movement. This time period would become known as “The Quiet Revolution”. Between the years of 1960 to 1966 the societal and political landscape of Quebec would drastically change. The people of Quebec, disheartened with the rampant corruption in the provincial government of Maurice Duplessis and his L’Union Nationale conservative party, the outdated traditional values of the Catholic church which seemed to permeate all aspects of society, and the dominance of the English bourgeois class, ushered in a new beginning for their beloved province with the election of Jean Lesage and the Liberal party in 1960.

READ MORE: THE QUIET REVOLUTION

Using the slogan “Maitre Chez Nous” (Masters in our own home) the Lesage government promoted many new reforms that called for more transparency and open debate in both the government and society and openly attacked the system of political patronage that had become predominant. Now with the opportunity to be untied from the church and the corruption of the past, Quebecers suddenly became outgoing, educated, and liberated. Everything was being questioned and discussed and the public took to discussing the notion of separation loudly and openly in public. With a new found freedom Quebec society had become predominantly secular and progressive in a relatively short time and feelings of separation were now able to thrive. In this environment came Charles de Gaulle’s infamous speech and less than one year later the separatist movement would have its first political materialization with the creation of a party whose sole purpose would be to promote the independence of La belle province.

The Lesage Liberals were internally filled with many separatists who longed for the day the government would address the issue of separation but were continuously dismayed. Chief among those was René Lévesque, a prominent cabinet minister who had overseen the popular policy of nationalizing Quebec’s hydroelectric industry in 1963. United with fellow indépendantistes and other defectors of the Liberal Party, Levesque called for the unification off all sovereigntists under one political party; a party that would be known as the Parti Quebecois (PQ).

On October 11th, 1968, the creation of the PQ was made official; Levesque and his team now had a monumental task in front of them: convince Quebecers that their ‘independent’ future lay with them. In an eight year struggle that saw Lévesque lose two consecutive elections, fail to win a seat for himself, and attempt to distance himself and his party from those who espoused violence as a means to negotiate independence (notably the militant group FLQ) the PQ team decided that the only way to achieve power was to campaign on a platform of good government and then bring forward separatism after their election.

READ MORE: FLQ AND THE 1970 OCTOBER CRISIS

The 70’s, 80’s and 90’s: Referendums and Constitutional Disagreement

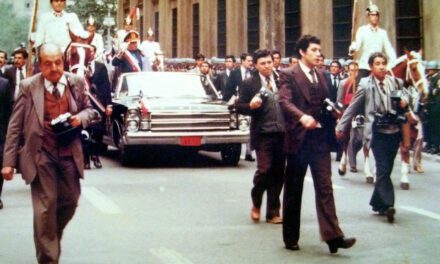

Lévesque finally led the PQ to victory in the 1976 provincial election. At his victory speech, with tears streaming down his face he declared “Never in my life have I felt so proud to be a Québecois.” In office the new Premier Levesque immediately set out to defend the linguistic values of Quebec, which he and much of his caucus believed had been neglected. With the passage of the Charter of the French Language, or Bill 101, in 1977 French became the official language of Quebec; residents were guaranteed that they would be able to be served in French in all public sectors including social and health services and all public enterprises. The Bill was seen by many as a jab to the bilingual policy of Canada, an attempt to isolate Anglophones and an indication that Quebec wanted to further alienate itself from the country.

The next step for the PQ was now the legal establishment of a Quebecois nation. With this, Lévesque and his cabinet devised the notion of ‘sovereignty-association’ a term proposed as the manifestation of a sovereign Quebec. First introduced in his published essay entitled La passion du Quebec, Lévesque brought forth a constitutional proposal that would allow Quebec to declare sovereignty while still maintaining an economic relationship with Canada. The PQ’s definition of sovereignty-association attempted to assuage fears that economic woes would follow an independent Quebec by ensuring that a formal association would be upheld with Canada; an association that would include free trade, common tariffs, and a common currency. Although widely denounced and campaigned against by various federalist political leaders like Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, a date for a referendum on Quebec sovereignty-association was set for spring 1980.

READ MORE: SOVEREIGNTY ASSOCIATION

On May 20th, 1980, as the results began to be reported it was clear the campaign the PQ had invested so much time into failed to reach fruition. With a final tally of 59 percent against sovereignty-association and 40 percent in favor it was obvious that Lévesque’s case for sovereignty had not been strong enough. But it was only a setback, and the results did not diminish the PQ’s popularity who were subsequently easily re-elected the following year.

After the failure of the 1980 referendum, René Lévesque and the PQ rallied to ignite the flame of Quebec nationalism once again. The results of the referendum indicated that Quebecers were not fully on board with sovereignty-association with Canada; in the immediate aftermath of the vote Prime Minister Trudeau’s federal government began the process of chartering a new Canadian Constitution, drafted in Canada, and free from Britain’s ability to enact amendments. But this process would require consultation with the provinces, and so Lévesque saw an opportunity in the Constitutional talks to have Quebec legally recognized as distinct from the rest of Canada.

Locking horns with Trudeau, Levesque demanded that Quebec would be recognized in the constitution as a ‘Distinct society’ and that the province would have the ability to opt out of federal-provincial transfers. These provisions, which were flat out rejected by Trudeau and failed to find consensus among the Premiers of the other provinces, produced bitter sentiment and Lévesque successfully used the situation to demonstrate the federal government had no interest in the future of Quebec. In the end the PQ refused to sign the newly minted Constitution, and when finally made into law on April 17, 1982, Quebec was the only province to have not signed and agreed to the terms of the Act. It remains so to the present day.

READ MORE: THE CANADIAN CONSTITUTION ACT, 1982

Feeling betrayed and left out of the talks, notions of another referendum were surfacing. However with the retirement of Trudeau in 1984 and the subsequent election of Brian Mulroney and the Progressive Conservatives the desire for another referendum was momentarily quelled. Mulroney’s government promised that Quebec’s frustrations would be rectified, and the province would have the opportunity to enter the Constitution and have its distinct nature recognized. Lévesque was elated and urged Quebecers to undertake what he called the ‘beau risque’ and support the Conservative government’s efforts to finally include Quebec; it was to be his last major move as premier. Several fellow PQ members were less eager to trust the federal government, despite Mulroney’s promises, and refused to accept any proposal. Facing internal dissension from the party and exhausted from twenty-five years in politics, Lévesque resigned as premier and leader of the party in 1985.

In the provincial election of that same year the Liberal party of Robert Bourassa defeated the PQ and just two years later Levesque died with the PQ still fractured. Nonetheless Mulroney’s pledge to include Quebec remained and Bourassa, although not sovereigntist in nature, would ensure that the Conservatives could not renege on their promise to recognize Quebec as a ‘distinct society’ constitutionally. Meeting with the premiers of all ten provinces, Mulroney negotiated a set of constitutional amendments in 1987 known as the Meech Lake Accord. The terms of the accord included greater autonomy for the provinces in immigration matters and most notably of all the recognition of Quebec as distinct. Although greeted with great hope the Accord failed to be ratified in all the provincial legislatures before the three-year deadline. Towards the end, the sentiment that Quebec was being treated specially at the expense of the other provinces greatly affected public opinion against the terms of the Accord.

For many Quebecois politicians, the trust that had been placed in the federal government with Meech Lake had been lost and a call for immediate action began. Most prominent in voicing discontent with the handling of Quebec’s constitutional gridlock was Lucien Bouchard, a Cabinet minister in the Mulroney government. Aligning with seven other MPs (five of which were in the Conservative government) Bouchard would defect from his party to form and lead a new sovereigntist one called the Bloc Quebecois (BQ). Its platform was designed to promote and defend the interests of Quebec at the federal level and ensure the requisite conditions for Quebec’s secession. The creation of the BQ marked the first time a separatist party was present at the federal level in Canadian history.

Affiliating itself with the PQ and capitalizing on the failures of Meech Lake, the BQ emerged out of the 1993 federal election with 54 seats, effectively sweeping most of Quebec’s constituencies and became the Official Opposition. The Progressive Conservatives were decimated being reduced to just two seats and a new Liberal government swept into power. Nonetheless Bouchard promised that the Bloc would be a responsible force in Parliament, not only criticizing the government but also seriously trying to make it work by putting forth constructive ideas both for Quebec and Canada as a whole. The rapid success of the BQ in such a short time successfully revived Quebecois nationalist sentiment and allowed for the PQ to win power provincially once again; former Lévesque cabinet minister Jacques Parizeau was elected as the party leader and Premier. Acting together as one mega political force the BQ and PQ, led by Bouchard and Parizeau respectively, set the stage for the second referendum on sovereignty for the newly ‘invigorated’ Quebecois.

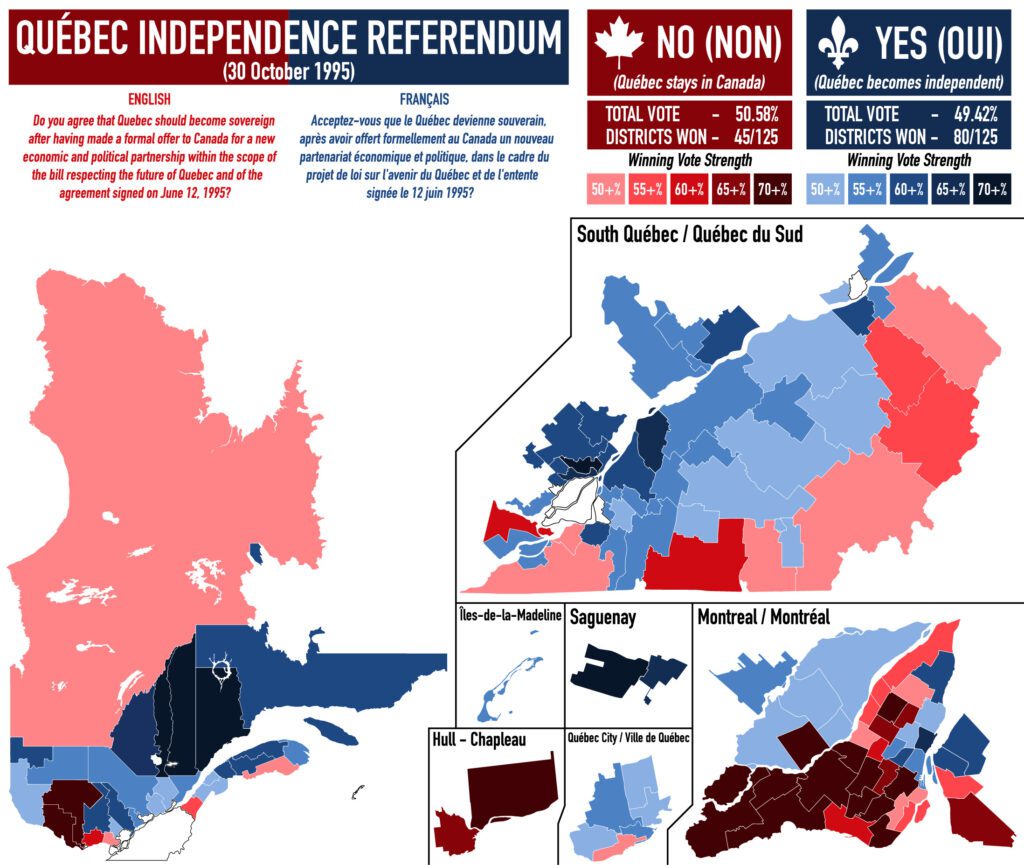

The hotly contested referendum campaign that pitted federalists against sovereigntists occurred on October 30, 1995. It shook Canadians across the country with the realization that Canada had never been so close to being divided.

Final tallies showed the narrowest of defeats for the sovereigntists; 50.5 percent had voted against sovereignty while 49.4 percent had voted in favor! For the BQ and PQ it was a crushing defeat, but also a clear indicator that the desires for separation was stronger than ever and the federal government could not just stand by and ignore Quebec any longer. A third referendum would be waiting in the wings…

READ MORE: THE NIGHT CANADA STOOD STILL

While it did not achieve its ultimate goal the Bloc Quebecois remained a dominant force in the House of Commons after the 1995 vote and continues to hold a strong level of support from Quebec electors. The PQ has alternated from forming government to filling the Opposition benches, though in the 2018 provincial election fell to third place in the provincial legislature.

In the sea of English that is the majority of the North American continent, Quebec stands as an island of the French language and culture. With all these historical developments, political parties, and constitutional squabbles, the question of Quebec’s place within Canada remains. Now the future of the movement for a sovereign Quebec waits to be written by a new generation of nationalists.

Listen to podcast episodes that detail this topic.

Articles you may also like

“The Best Show That Was Ever Staged”: Charles Ponzi’s Scheme

Reading time: 7 minutes

Having gambled away his life savings on the passage over, Italian immigrant Charles Ponzi arrived in America with next to nothing in his pocket. As he would later recount, “I landed in this country with $2.50 in cash and $1 million in hopes, and those hopes never left me.”

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.