Estimated reading time: 5 minutes

By Madison Moulton

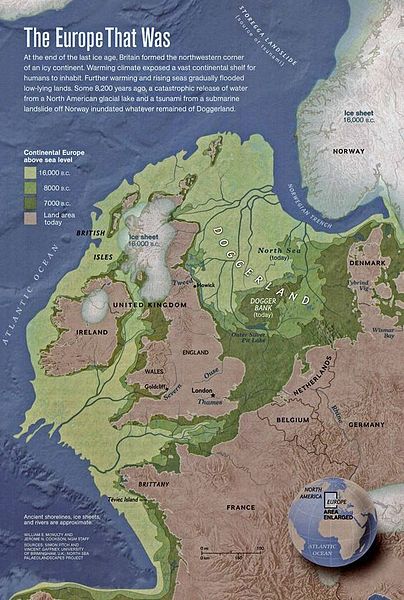

Looking out at the North Sea – the body of water dividing Britain and the rest of Europe – you would never suspect this hub of marine activity was once not a marine environment at all. However, beneath the sea lies evidence of a lost world – a mass of land that previously connected Europe, known as Doggerland.

Discovering Doggerland

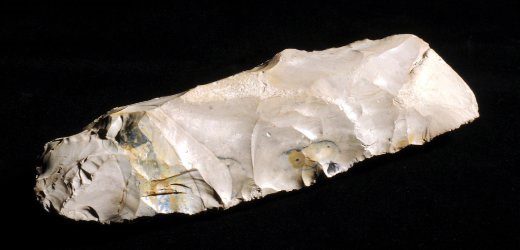

The first discoveries suggesting the existence of a previously inhabited land under the sea were made in the 1900s by those most familiar with the waters – fisherman. Fishing trawlers, dragging nets along the seafloor, brought more than fish to the surface. They found animal tusks, Mesolithic and Neolithic tools, and fragments of human bones throughout the century. They were first ignored or attributed to coincidence until peat and fossilized forests were discovered beneath the seafloor. Archaeologists, certain these findings were evidence of a human settlement below the North Sea, began to investigate the area. They named the area Doggerland after Dogger Bank, a large sandbank in the North Sea.

Since then, archaeologists and scientists have mapped 43 000 square meters of Doggerland. Seismic surveys and sediment samples from research expeditions have helped reveal it’s topography. This research, and the objects found along the ocean floor, give insight into how Doggerlanders lived thousands of years ago.

How Doggerland Became the ‘Atlantis’ of the North Sea

Around 10 000 years ago, as Europe was coming out of the last ice age, ancient hunter-gatherers of the Mesolithic period inhabited Doggerland. The rich habitats of marshlands, valleys, rivers, and lakes drew groups from all over, looking for fish, birds, and a freshwater supply. Archaeologists predict Doggerland spanned from Britain’s East coast to the Netherlands – about a quarter the size of Europe itself.

The surface area slowly decreased as ice sheets melted and sea levels rose, submerging the low-lying lands under the sea. Researchers have confirmed a tsunami, triggered by an underwater landslide near Norway known as the Storegga slides, hit around 6150BCE. Some parts of Doggerland may have survived the event, protected by the land’s topography. But the remaining islands were finally submerged years later, creating the image of the North Sea we know today. Rising seas enveloped a lost world hidden beneath the ocean, that we are only just beginning to understand.

Life in Doggerland

Early Doggerlanders lived in coastal areas near rivers and lakes, hunting and fishing for sustenance. They used tools made from stone or animal remnants and lived amongst large mammals unknown to us today. Due to the size of the area, historians believe thousands of people, grouped with different cultures and survival methods, inhabited Doggerland. Unfortunately, artifact discoveries and evidence of human activity are few and far between. The suspected human settlements are difficult to excavate under layers of silt from rivers like the Rhine and Meuse.

Most of the available evidence tells us more about the environment they lived in than the people themselves. Pieces of petrified wood reveal the existence of a submerged forest, and the hills and valleys surrounding them. Compressed peat below the seafloor (one of the first significant finds confirming the land was once above sea level) distinguishes areas of wetlands that were ideal for fishing and hunting birds. According to researchers, the concentration of resources in Doggerland indicates they were more settled than typical hunter-gatherer societies.

Due to rising seas and the Storegga tsunami, major population displacement occurred, changing the topography slowly but significantly. Although historians believed the tsunami was the final nail in the coffin for Doggerland, a recent 2020 study by British and Estonian scientists showed a small part of Doggerland (and Doggerlanders) survived the aftermath. History Guild Members can read the paper in the Library here. A great wave: the Storegga tsunami and the end of Doggerland?

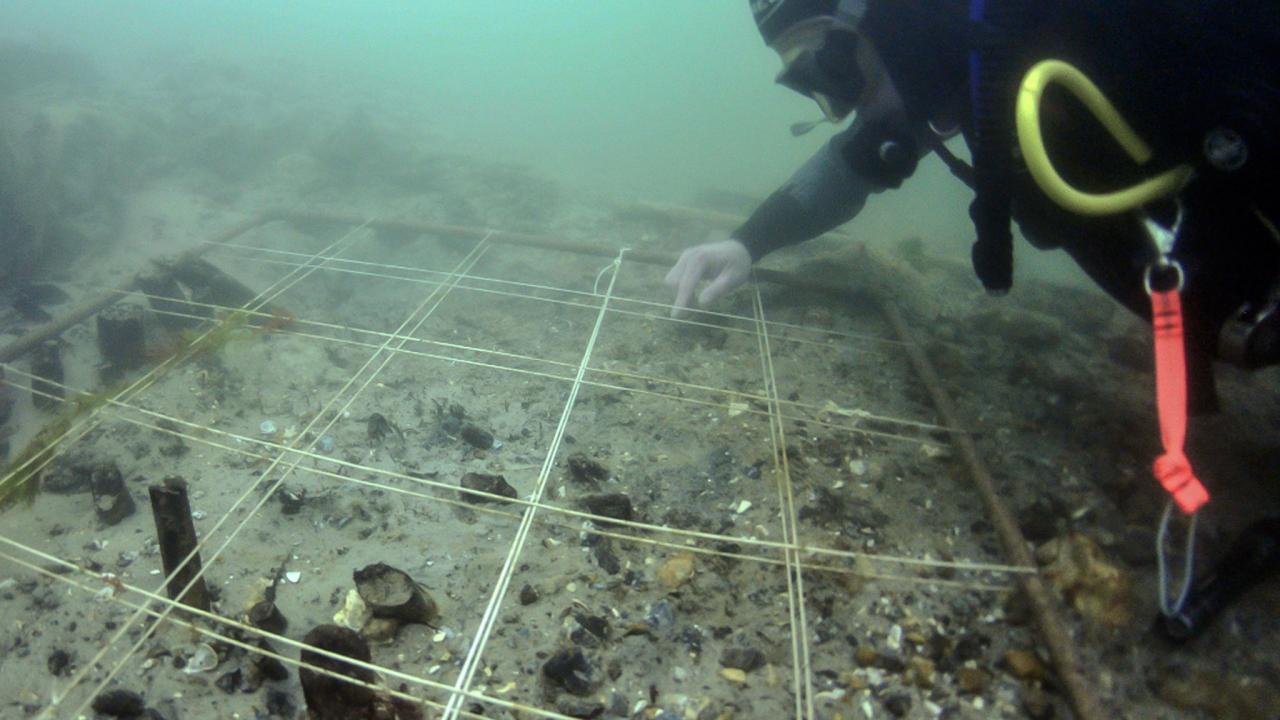

The remaining people were possibly the first in Britain to transition from the Mesolithic hunter-gatherer lifestyle to Neolithic farming practices. But, their land was finally drowned by the rising seas years later. Archaeologists are hoping to find settlements in areas mapped by seismic surveys using new techniques in underwater archaeology. However, as Doggerland is tucked beneath tons of water and silt, successful excavation has its challenges.

The Challenges of Underwater Archaeology

Underwater archaeology has intense challenges to overcome when compared to land archaeology. Researchers contend with poor visibility and harsh ocean conditions. There are prohibitive costs like specialized equipment and ships needed for the expeditions. And the expanse of the North Sea makes finding evidence that much harder – a needle in a giant haystack. Sonar and seismic technology 3-D map the area, giving researchers a clearer picture of where the settlements may have been and a higher chance of finding artifacts in these areas.

Despite its challenges, archaeologists are confident they are close to discovering a complete settlement in the next few years. Oil and gas companies have aided research funding, and archaeologists hope the wind farm developments in the North Sea will provide a perfect opportunity for further research and discovery. This will reveal even more about the early Britons, including their daily habits, migrations, and cultural practices.

Although it may not look like it (and hasn’t for thousands of years), we now know looking out at the North Sea that a lost continent lies beneath. Its central position and connection to many parts of Europe suggest Doggerland was possibly the heartland of Mesolithic Europe. Continued research in this area will help us understand this heartland and the Mesolithic and Neolithic Britons who inhabited it. We may also discover how Doggerlanders tackled the problem of rising seas, giving us insight into how we may deal with the same problem in the 21st century.

Articles you may also like

Why the Legions Beat the Phalanx

The societies of ancient Greece and Rome valued brawn as well as brains. Philosophers fulfilled military service and some of the most masterful speeches held in the senate or agora argued for war. However, it was the Romans that would end up dominating the Greeks, which was largely to do with the way they fought […]

Fantastic article, and your site looks very interesting, would love to receive newsletters