Reading time: 9 minutes

From humble beginnings and over centuries, Britain built an empire by conquest, diplomacy, and economic muscle whose deep marks on the world and its history have been, and will be, felt for many years to come. One of the most fascinating ways this maritime nation changed the world was by forging ties between disparate nations and nationalities, like Malta and Australia, which endure to this day.

By Morgan WR Dunn

One of the smallest island nations and one of its largest have a long and complex shared history. This is the story of Australia and Malta when it came to its highest pitch during the uproar and tumult of the 20th century.

MALTA & AUSTRALIA AT THE ROOT

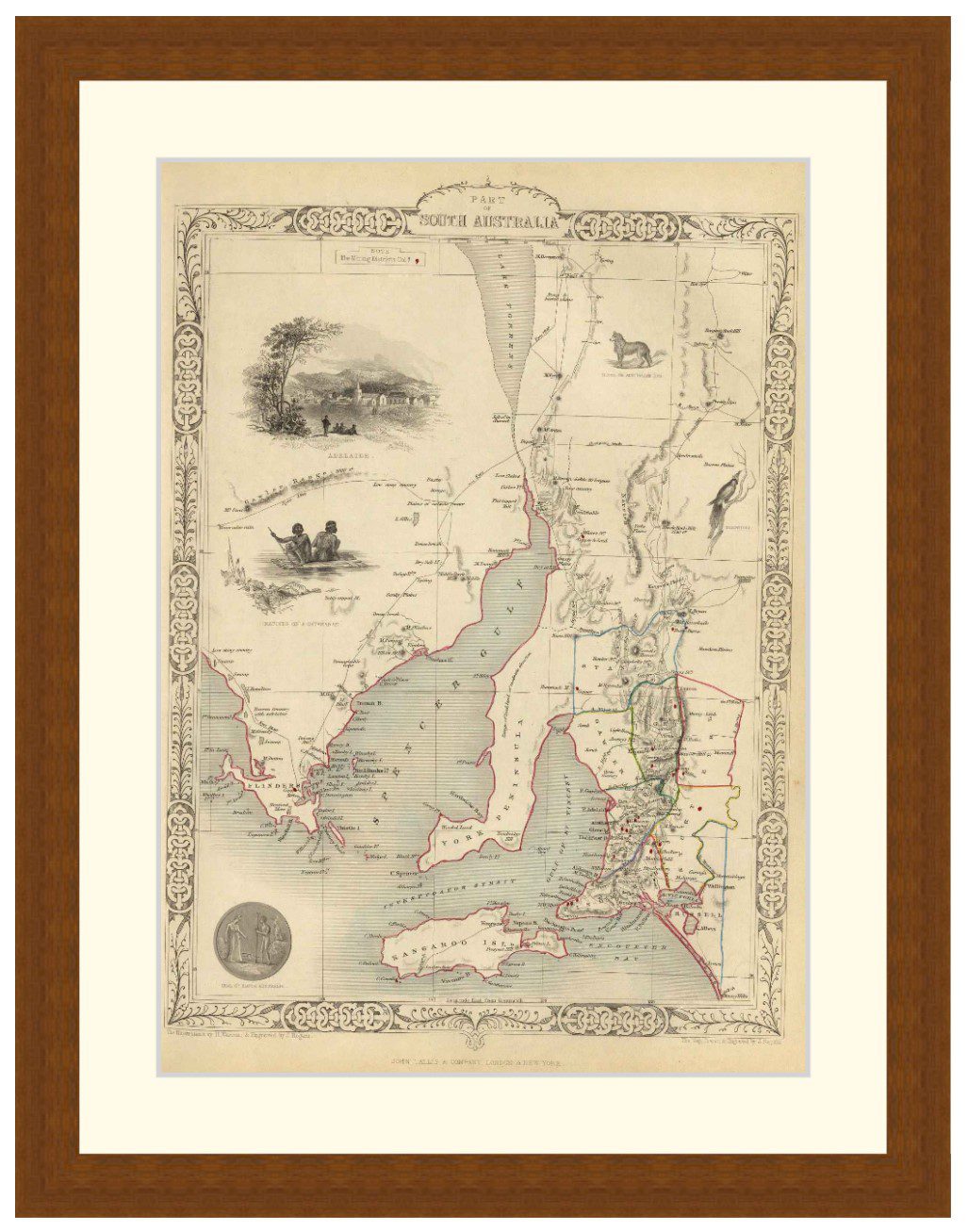

When the first European settlement in Australia was established at Botany Bay in 1788, Malta had already been continuously inhabited for nearly 8,000 years. A decade later, a military quirk of fate thrust the Maltese archipelago into the British sphere when, after a two-year siege, the French garrison in Valletta surrendered the island to British forces in 1800.

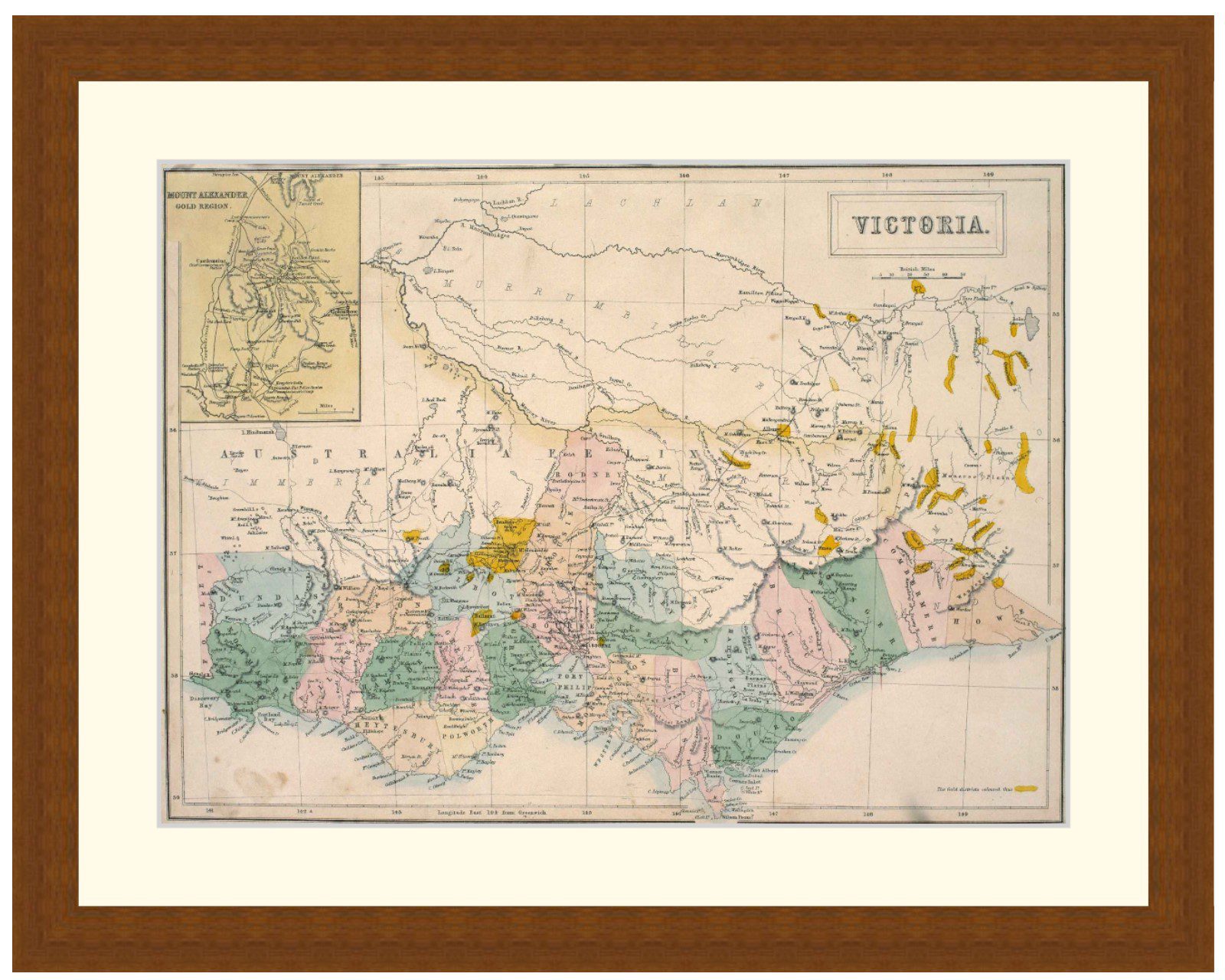

Malta, now a dominion of the British Empire, was also subject to its laws, and by 1821, the first Maltese settler to reach Australia, convict Salvatore Diacono, was recorded at Parramatta. With the arrival of free settler Antonio Azzopardi in Victoria in 1839, the bedrock of the islands’ relationship was formed.

Maltese settlers arrived in Australia throughout the 19th century, such as a group of 70 laborers who arrived in 1883, but their numbers remained low, with a Maltese population of only 73 in Victoria in 1881.

Australia took its first unified step toward nationhood at the dawn of the 20th century. In 1901, the six colonies on the island continent combined to form the Commonwealth of Australia. This proud day for the colonies’ inhabitants was marred by the passage, just months later, of the Immigration Restriction Act 1901, setting in motion a longstanding policy now known as the “white Australia policy.” The act gave Australian officials broad powers to turn away anyone who was a “prohibited immigrant” — and at the time, that included Maltese migrants.

Despite the official prejudice, small numbers of Maltese immigrants still made it to Australia, notably settling in Sydney. Rural Maltese gravitated to the Pendle Hill district, while natives of the few towns and cities in the archipelago found work as fishermen, dockers, and in small businesses in Woolloomooloo.

The relationship between the two island peoples was off to a rocky start. Fate intervened again, however, when a catastrophe they couldn’t have foreseen broke out: in August 1914, Britain declared war on the German Empire.

THE FIRST WORLD WAR

During the First World War, Malta sealed its place in Australia’s national mythology by participating in some of the most defining moments of the Commonwealth’s history. As soon as war was declared, Australia began to assemble its first army. Malta was to affect this force in two key moments in the early war.

GALLIPOLI

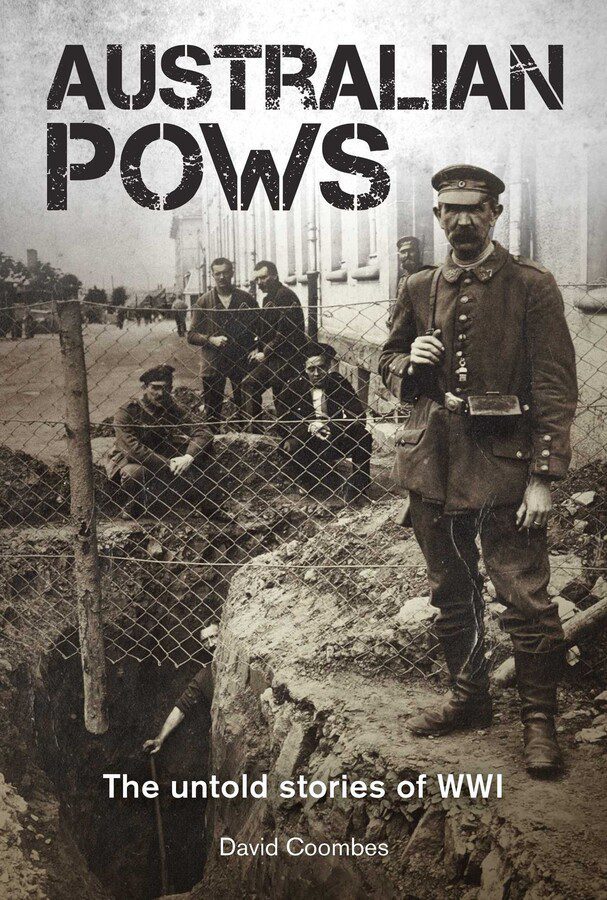

When AIF forces arrived in Egypt, they were combined with New Zealand troops to form the Australia and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC). Originally intended for service on the Western Front, in 1915 the Corps was diverted to the Gallipoli Peninsula in Turkey after naval forces of the Triple Entente failed to open the Dardanelles strait.

The ensuing Gallipoli Campaign became as much a founding myth as a waking hell for the men who fought it. Over ten months, the number of wounded climbed so high that hospitals in Egypt were overwhelmed. Malta, ideally situated to support the attack on Turkey, had just four military hospitals in 1914. Within a year, 27 hospitals and seven convalescent stations were in operation on the islands.

Malta, wrote chaplain Reverend Albert Mackinnon, “…assumed the role of nurse, and her breakwaters seem like arms stretched out to receive her burden of suffering. Once the hospital ship has passed within their shelter the rolling ceases, and the wounded feel that they have reached a haven of rest.” When it was published in 1916, Mackinnon’s book, Nurse of the Mediterranean, was among the earliest instances of that title for Malta. The reputation it signified was also one of the first and strongest planks in the relationship between the two countries.

Besides treating their wounds, the Maltese shared in the Australians’ frontline dangers, too. Several Maltese Australians served with Australian forces at Gallipoli. One, Private Charles Emanuel Bonavia, was among the first to die in action on the first day of the campaign.

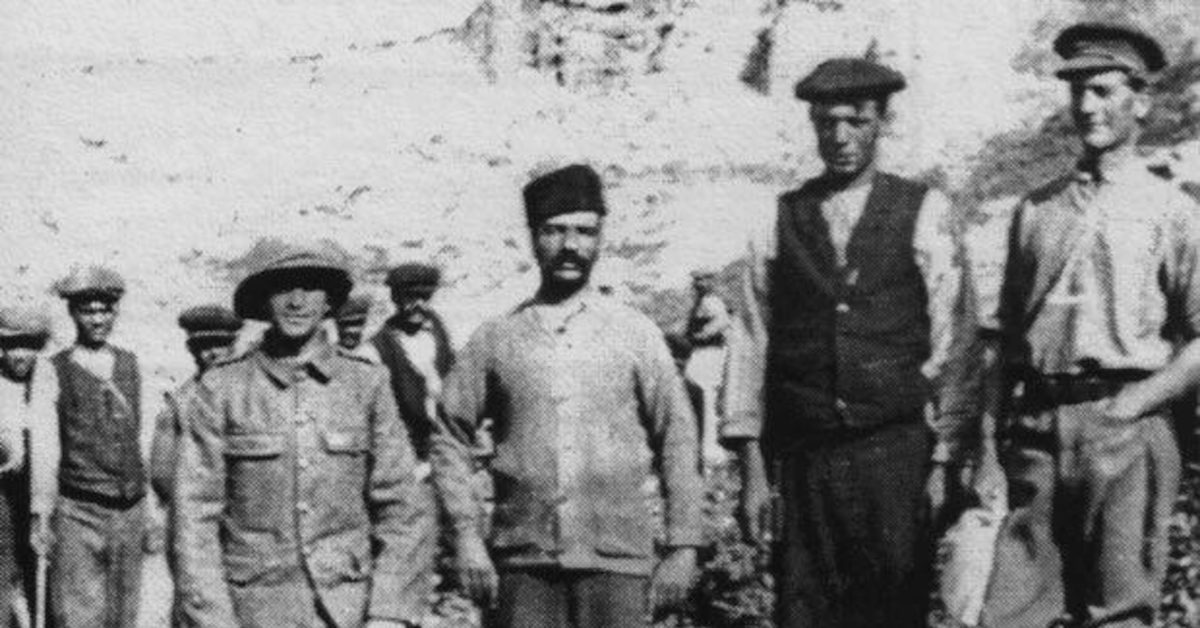

When the King’s Own Malta Regiment of Militia returned from occupation duties on Cyprus, 1,000 of its men volunteered for labor service at Gallipoli as members of the Maltese Labour Corps. Working close to the front to deliver supplies, cook food, dig trenches and cut paths, and aid the wounded and dying. Several died during the campaign, earning a reputation among the Australians as tough, brave, hard-working men on whom they could depend.

THE GANGE INCIDENT

In spite of the bond being forged between Australians and Maltese in Europe, at home in Australia older prejudices still held sway. In October 1916, as Australians fiercely debated the issue of conscription, a French ship, the Gange, approached Western Australia carrying 214 Maltese laborers. Many were veterans of the same Maltese Labour Corps which had been at Gallipoli.

Under the White Australia policy, immigrants were required to pass a literacy test in a European language before being allowed to disembark. The Maltese passengers naturally failed to pass a test in Dutch and were shipped on to New Caledonia. Prime Minister Billy Hughes, desperate to secure a “yes” vote in an upcoming conscription referendum, gave way to public paranoia that the “coloured labourers” were the first of a mass importation, a conspiracy to free up Australian men for military service.

In the end, the October 1916 referendum failed, and another in 1917 was even more resoundingly defeated. The Maltese, who were extremely popular among ex-servicemen, were allowed to return to Sydney after four months in limbo and then to settle in the country. They and their descendants would eventually call themselves “il-tfal ta Billy Hughes” (“the children of Billy Hughes”).

THE MID-20TH CENTURY

With the war over, Australia hosted a small but strong Maltese community. In 1920, a new quota system was established to allow Maltese who met certain conditions, such as aptitude in the English language, to immigrate. With the quota capped at 260, aside from dependents of settled Maltese Australians and Maltese holders of Australian passports, the Maltese population remained small, with just 395 Maltese-born Australians living in Victoria alone by 1933.

The Second World War shifted the balance far more strikingly than the first. Common ground, now strengthened by the support of the Maltese people for Australian pilots and sailors who’d operated from the islands against Italy and Germany, was firmer. Moreover, the White Australia policy was undergoing reforms. While it would only be in the 1960s that the policy was fully abolished, in the immediate postwar period Australian governments were more accepting of European immigrants hoping to settle in the sparsely-populated country.

Hundreds of thousands of Europeans flocked to the southern continent in the late 1940s. A clear sign of the changing times came in 1948, when Australia established an assisted passage agreement, the first with any country other than Britain, with Malta. By 1966, reports Museums Victoria, the Malta-born population of that state was 26,452. Many came to work in Australia’s automotive industry.

INDEPENDENT NATIONS

After WWII, Malta achieved home rule and, after briefly considering joining the United Kingdom itself, became an independent nation on 21 September 1964. Among the first four nations to establish bilateral diplomatic relations with the new state on that day was Australia. It marked the emergence of the two island nations into a new era of mutual respect and cooperation.

With the transition to a republican government in 1971, the Maltese Labour Party introduced sweeping reforms to establish a robust welfare state and to extensively democratise Maltese society. These changes, combined with the growing economic prosperity of the country, gave Maltese citizens fewer and fewer reasons to leave. Emigration to Australia tapered off; by the time Maltese historian Henry Frendo had arrived in Queensland in 1984, Maltese-Australian mothers came to visit his pregnant wife in the hospital “to see a real Maltese.”

Over 200 ANZAC dead are buried in Maltese cemeteries, and the countries’ shared wartime experiences form part of the basis of long-lasting military, political, economic, and cultural ties. Today, nearly 200,000 Australians have Maltese ancestry, the vast majority living in Victoria and New South Wales, and many speak the island’s unique Semitic language at home. They form, with their distinctive culture, family histories, and experiences, part of the vibrant fabric that is today the Australian people.

Podcasts about Australians in the Mediterranean during WWII

Articles you may also like

A History of the Great War, Volume One – Audiobook

A History of the Great War, Volume One – AUDIOBOOK By John Buchan (1875 – 1940) This is the first of a four-volume history of the First World War, covering the period from its outbreak in the summer of 1914 to the campaign in Neuve Chapelle of March 1915. The author, John Buchan, was most […]

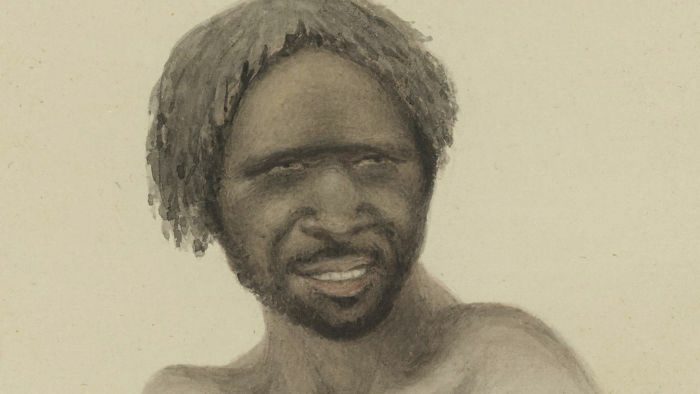

Tongerlongeter — the Tasmanian resistance fighter we should remember as a war hero

Reading time: 3 minutes

Australians love their war heroes. Our founding myth centres on the heroism of the ANZACs. Our Victoria Cross recipients are considered emblematic of our highest virtues. We also revere our dissident heroes, such as Ned Kelly and the Eureka rebels. But where in this pantheon are our Black war heroes?

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.