Reading time: 5 minutes

Sheila Sibley enlisted in the Australian Army in 1942 with a vision of becoming a wartime nurse – “an angel of mercy, the wounded man’s guide … the Rose of No-Man’s Land”, in her own words.

Many women wanted to “do their bit” during the second world war, and nursing had previously been the only avenue for women to join the military. They had historically been excluded from traditionally masculine roles within the armed forces.

By Jason Smeaton, Australian Catholic University

Sibley, however, never became a nurse. Ideas of becoming “this war’s Florence Nightingale” were let go, and nursing was left to those who had trained for it.

Private Sheila Sibley instead served in a hospital kitchen and then laundry.

The establishment of women’s auxiliaries to Australia’s military in the early 1940s created new opportunities for women. This included expanded roles in military hospitals, but also jobs that reached far beyond the hospital ward. Women were called to serve as signallers and telegraph operators, mechanics, and even coastal artillery and anti-aircraft gunners.

These jobs were a clear break from the expected role of women at the time.

However, my research shows servicewomen like Sibley had to fight on another front: to have their contributions to the war acknowledged, in a time when much of their efforts were considered “women’s work”.

The battle for hygiene

In January 1941, 200 Australian servicewomen marched-in as orderlies to support Army nurses working in the Middle East. At first, they were given laborious jobs such as reclaiming bandages for reuse, “regardless of how revolting they were”, according to Sibley’s colleague Alice Penman.

Soon the nursing sisters trained the female orderlies in tasks such as dressing patient wounds.

Stories from servicewomen in the Middle East were returned to Australia and they encouraged other women to join them. “Work hard,” said servicewoman Rita Hind, “because I am sure it is going to be a marvellous experience.”

Military officials also heard the stories of these women and noticed they had become a skilled and useful resource for the hospital.

In December 1942, these servicewomen were given their own branch of the Army, known as the Australian Army Medical Women’s Service. With the creation of the new auxiliary, servicewomen’s roles in military hospitals expanded to include those alongside nurses in patient wards and operating theatres, to those “behind the scenes” of hospitals such as in pathology laboratories, kitchens, laundries, and postal and telegraph offices.

Assigned duties that were considered then as “menial”, “domestic” or the “work of a housewife”, servicewomen working in the fundamental areas of hospital efficiency struggled to be seen.

Today, the COVID pandemic has illustrated the important work of all those who contribute to the health system. But there are few stories told about the historical work of women who toiled behind the scenes to ensure military hospitals ran efficiently and effectively during the second world war.

Posted to duty in the laundry of the 115 Australian General Hospital (AGH) at Heidelberg, Victoria, Sibley came to appreciate that the laundry was fundamental to the maintenance of hygiene in hospitals. “Everyone who works in a laundry at an AGH,” Sibley suggests, “is fighting for the lives of the wounded as steadfastly as that clever surgeon.”

The correlation between hygiene and the health and recovery of patients was still in its infancy in the 1940s. Laundry work was also still considered to be “women’s work”.

Sibley stood up against the gendered portrayals of her wartime work. A hospital laundry bears no resemblance to its domestic counterpart with its industrial machinery to wash, dry, iron and fold linen and clothes. To Sibley, the laundry was the battlefront and the machines her weapons. She wrote:

What may look like a washing machine in our big military hospitals is really artillery firing its rounds of good clean washing against the enemies, disease and death.

Fighting stereotypes

The strategy of other servicewomen to break from gendered boundaries was less overt.

Sergeant Thelma Powell quietly worked in her role at the No. 1 Facio-Maxillary and Plastic Unit where she became an artist painting artificial eyes for injured soldiers.

Before the war, Powell had an interest in fine art through her hobby of smoke-etching china. It was through her fine attention to detail and her meticulous care in the highly technical work of painting artificial eyes that Powell pushed back on expectations of women at the time.

Powell showed that the skills from a “hobby for women” could be applied to an important occupation directly affecting the rehabilitation and lives of injured men.

Given the ingrained gendered expectations within society at the time, the attempts of those like Powell and Sibley to highlight servicewomen’s work and afford their labour proper recognition were overshadowed.

Patients noticed their care, and medical professionals relied on their service, but their stories have not been told.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Podcasts about women of WW2:

Articles you may also like:

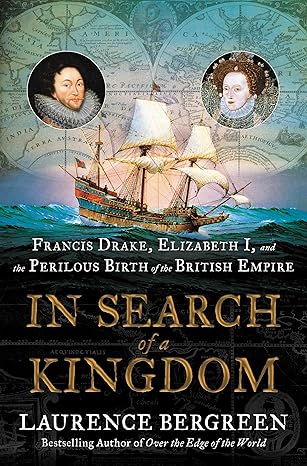

IN SEARCH OF A KINGDOM: FRANCIS DRAKE, ELIZABETH I, AND THE PERILOUS BIRTH OF THE BRITISH EMPIRE – BOOK REVIEW

A review of the “grand and thrilling” book “In Search of a Kingdom: Francis Drake, Elizabeth I, and the Perilous Birth of the British Empire” by Laurence Bergreen.

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.