Reading time: 6 minutes

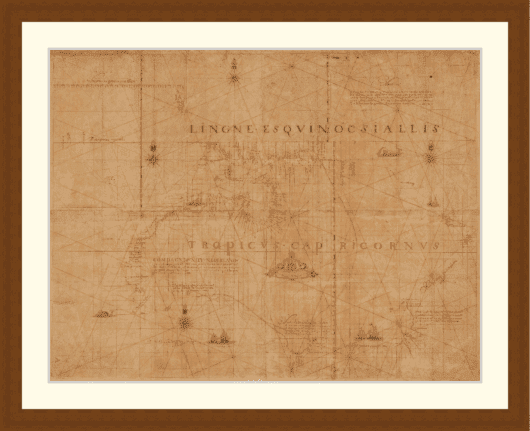

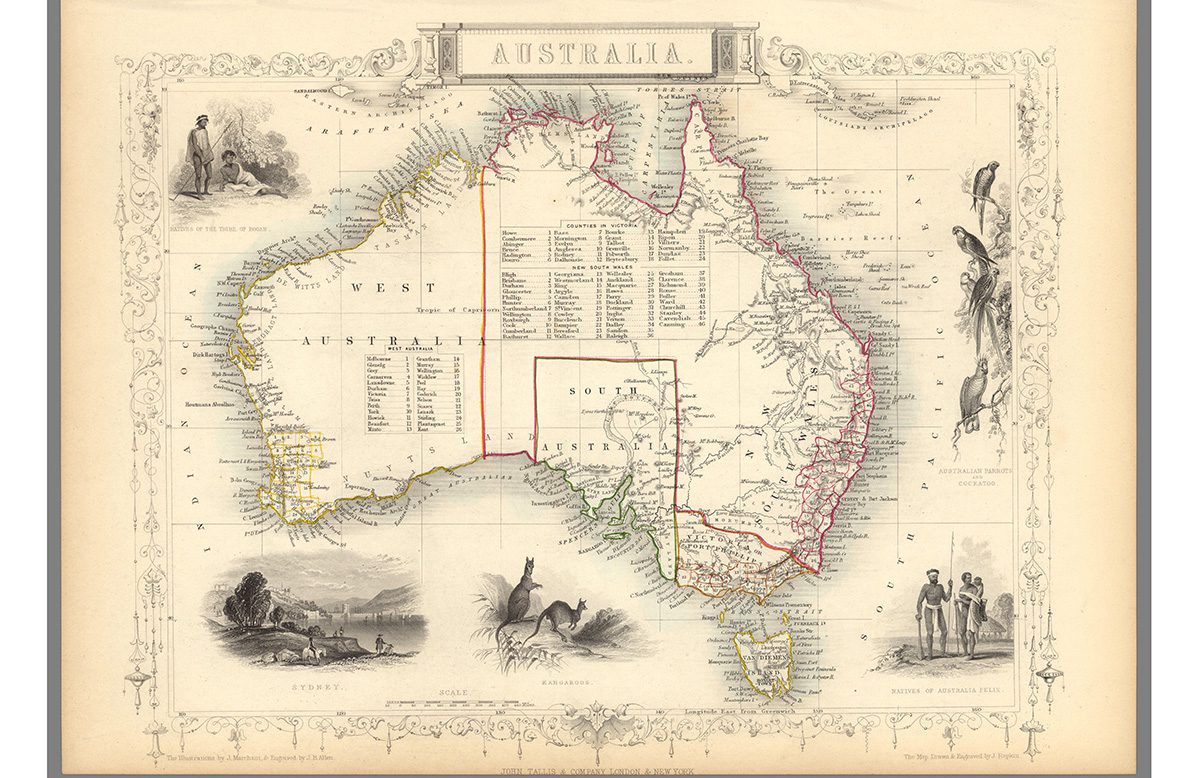

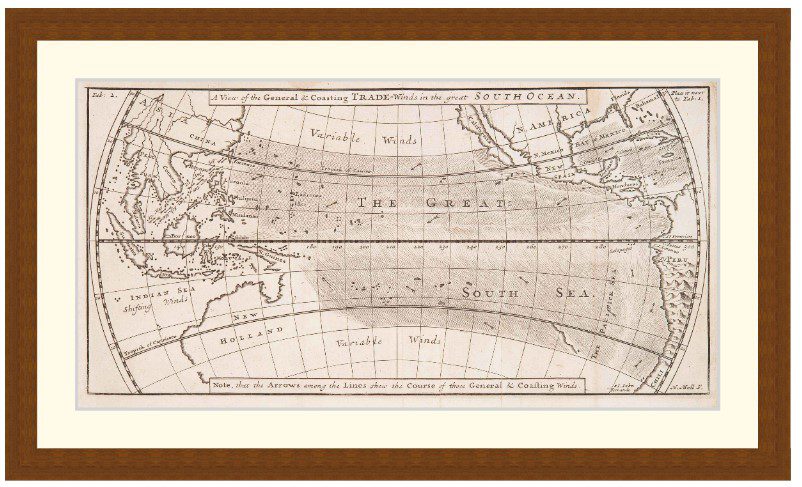

Every year, tens of thousands of New South Wales State Library patrons walk past a stunning mosaic replica of the Tasman Map on the floor of the Mitchell library vestibule. The original Tasman map, recently restored, charts the two voyages of the Dutch explorer Abel Tasman in 1642 and 1644.

The map is perhaps the Mitchell Library’s greatest treasure, though we know little about the time, place, or artist responsible for it.

Yet as we discuss in a new paper, its acquisition by the Mitchell library is a story of subterfuge, intrigue, personal animosities and state-versus-commonwealth rivalries.

The Tasman Map was probably made in the mid- to late-1600s in Batavia (now known as Jakarta), home of the Dutch East India Company, on Japanese paper.

By Lynette Russell, Leonie Stevens, Monash University

It was most likely compiled by a team of draftsmen from a range of charts from Tasman’s two voyages. One of the artists was almost certainly Isaack Gilsemans, draftsman on the voyage.

Mystery shrouds the map’s whereabouts from the 17th century until 1843, when Amsterdam mapmaker Jacob Swart described and reproduced it.

In 1891 the original 17th century map was listed for sale by Frederick Muller & Co. An interested group headed by historian George Collingridge tried unsuccessfully to persuade the NSW government to purchase it.

Instead, the map was purchased by Prince Roland Bonaparte, great-nephew of Napoleon, and an anthropologist with a great interest in Australia.

The princely promise

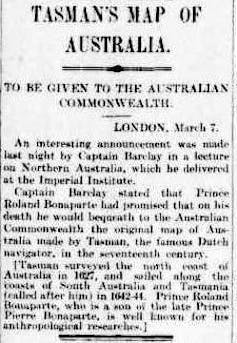

In March 1899, Henry Vere Barclay – a failed pastoralist, explorer and raconteur – gave a talk at the Imperial Institute in London where he announced Prince Roland had promised the Tasman map would be bequeathed to the Australian Commonwealth Government.

Within days, headlines declaring Prince Roland’s intended gift of the map to the Commonwealth of Australia had appeared in at least 44 Australian and New Zealand newspapers.

The prince’s intention to bequeath the map was confirmed in 1904 by James Park Thomson, president of the Royal Geographical Society of Queensland.

After viewing the map in Paris, Thomson wrote in his memoir, Round the World, of how the prince believed the map would be “of the greatest interest and use to the Commonwealth.”

Also reported by Thomson was how the prince wanted to hand the map to the Commonwealth government in person – but he was terrified of snakes and disliked rabbits which “seemed to overrun the place”.

Murmurings about the Tasman map fell silent for two decades and only emerged again after the prince’s death in 1924.

A clandestine operation

In 1926, anthropologist Daisy Bates read Thomson’s book, noting the reference to Prince Roland’s intended bequest.

Knowing the prince had recently died, she wrote to an acquaintance, William Ifould, asking him to enquire of the prince’s estate and the status of the map.

As chief librarian of the NSW Public Library, Ifould immediately began a clandestine operation to bring the Tasman Map to Australia.

It is clear from his earliest communications, when he warned his agent not to let the map come to the attention of Prime Minister Stanley Bruce, that Ifould was consumed by a singular goal: to acquire the map for NSW before anyone from the Commonwealth government remembered the prince’s promise.

Ifould’s chief personal nemesis was Kenneth Binns, librarian of the Commonwealth National Library, but Ifould also held an abiding antipathy for the Commonwealth itself.

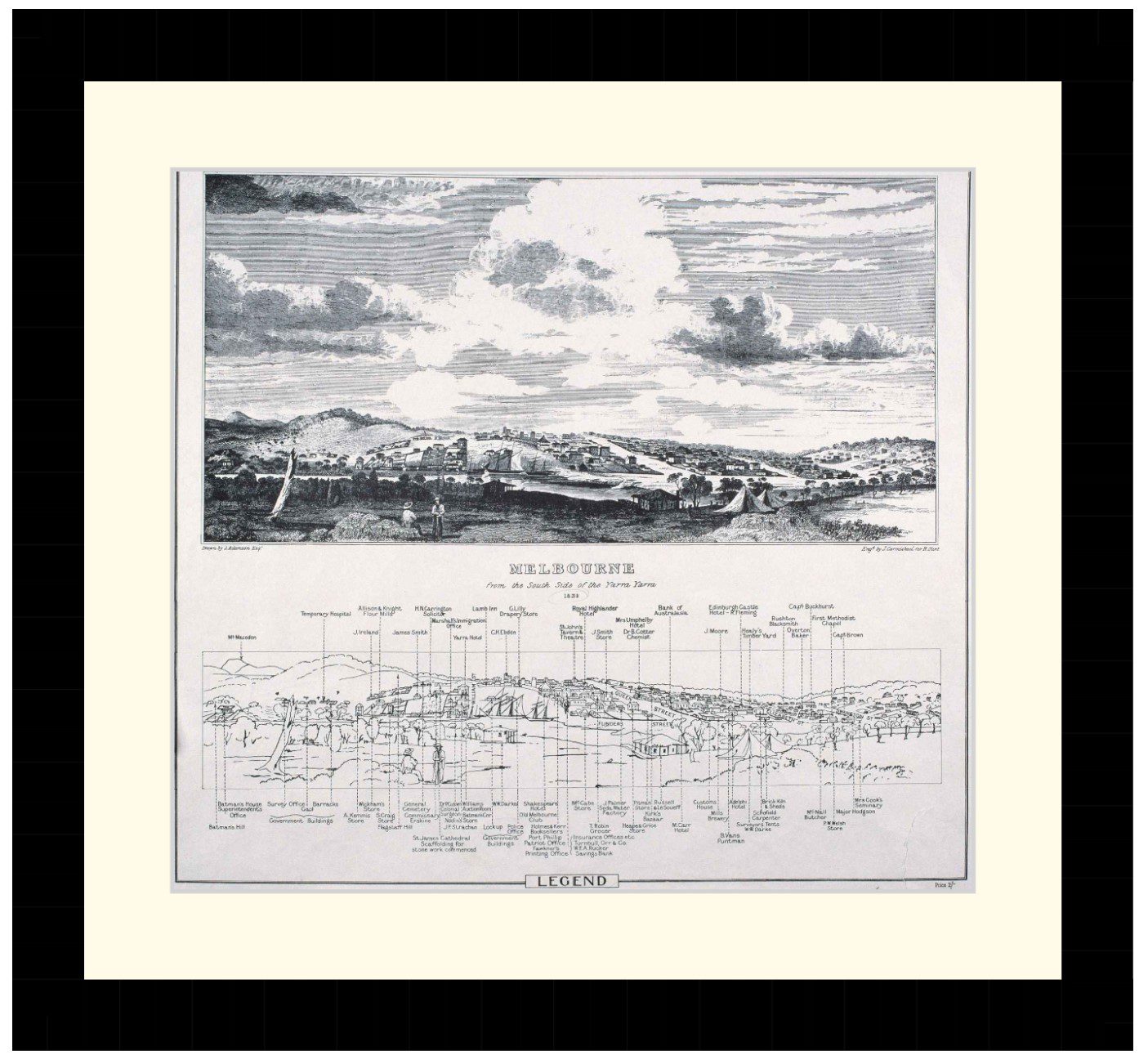

In the earliest days of the scramble for the map, the Commonwealth Library’s collection was yet to have a permanent home, with the national capital of Canberra still in the early planning stages. Binns was based in Melbourne, then the seat of the national parliament, and this played into a rivalry between Sydney and Melbourne.

The Tasman Map was in the possession of Princess Marie Bonaparte, who was aware of her father’s desire to bestow it upon the Australian nation. Her husband Prince George wanted to travel to Australia and present the map himself.

This created concern for Ifould and the Mitchell Library, who were worried they might accidentally present it to the prime minister instead of the Mitchell Library.

Princess Marie clearly considered the map belonged to the Australian Commonwealth.

Ifould and his conspirators – including a succession of British ambassadors and NSW agents-general – ignored this. As one agent-general advised the NSW premier:

it is probable that she does not mean to say the Map will go to the Commonwealth Government, and that the use of the words ‘Government of Australia’ has no particular significance.

In May 1932 came the breakthrough Ifould had been waiting for: Prince George postponed his trip again, and Princess Marie agreed to hand the map to the Paris-based Australian Trade Commissioner.

Ifould’s seven-year clandestine operation, came to fruition when the map, now known as the Bonaparte-Tasman Map, arrived in Australia to great fanfare in September 1933.

A global map; a local rivalry

Absent from any version of the story over the past 90 years is admission of knowledge of Prince Roland’s wish, expressed multiple times, for the map to go to the Commonwealth.

The role of Barclay’s 1899 anecdote, and its publication around the country, was eradicated. This allowed the map falling into the Mitchell’s hands to be characterised as a happy coincidence, and not the result of scheming and subterfuge.

The Tasman Map, as it is commonly viewed today, is a mosaic reproduction by Italian artisans, of a Dutch map, on Japanese paper, depicting Antipodean coastlines, representing east Asian dominance, donated by a French aristocrat, intended for the Australian Commonwealth, but wrested by a state institution obsessed with inter-library rivalry.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Articles you may also be interested in

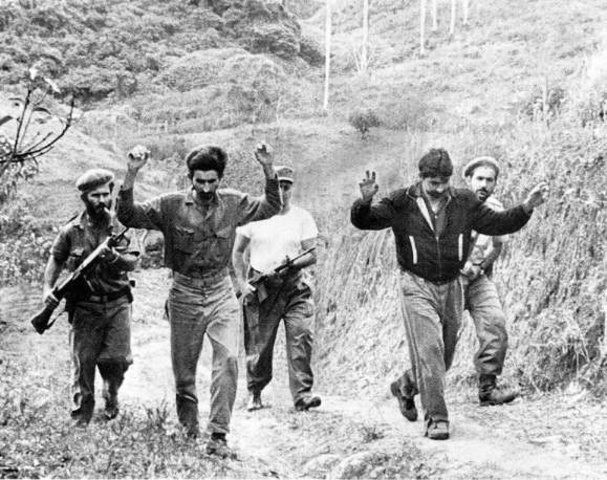

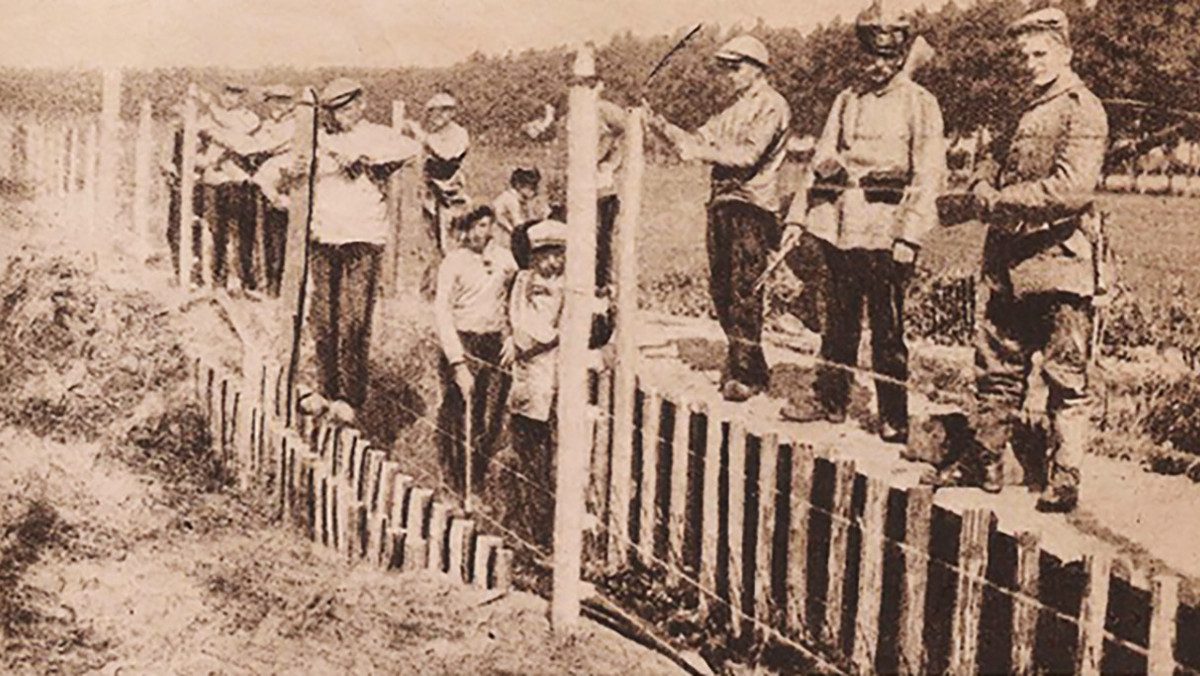

When Australia Fought France, WWII – Video

Operation Exporter was a little known, but very important campaign for the Australian military. It involved Australian’s fighting a strange war against confused Frenchmen who were not supposed to be our enemy. France had been defeated and subjugated by the Germans. The new French government, installed at Vichy, was answerable to the Führer. With France vanquished, the fate of their territories in Syria and Lebanon became uncertain.

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.