Estimated reading time: 6 minutes

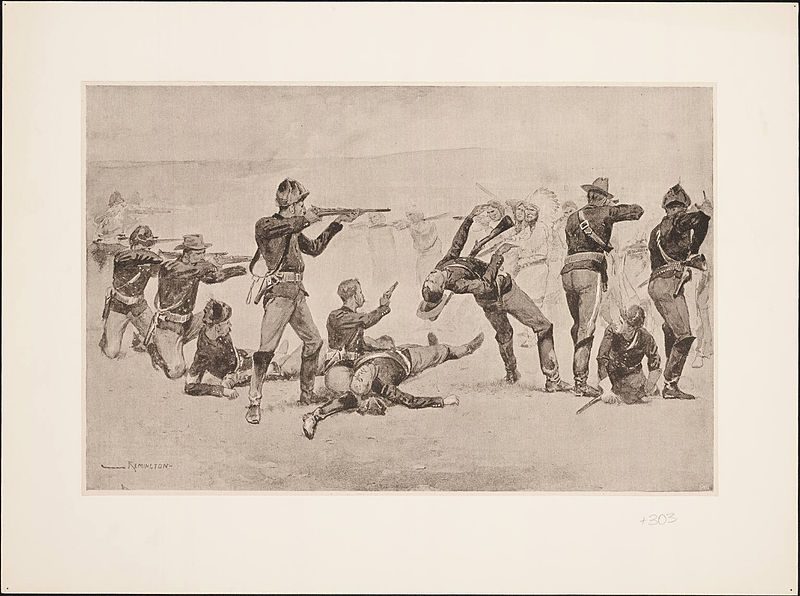

On 29 December 1890, between 150-300 Sioux Lakota men, women, and children, most of whom were unarmed, were killed by the United States military. Known as the Wounded Knee Massacre, after Wounded Knee Creek in the Pine Ridge Reservation, South Dakota, this event has attracted recent attention due to the twenty Medals of Honour awarded to the soldiers involved. Today, there is increasing support for the movement requesting the US government rescind these medals, labelling them ‘Medals of Dishonour’.

By Madison Moulton

Sitting Bull and the Ghost Dancers

By the end of the 19th century, the Native American population faced crises of land and culture. Forced removals, assimilations, massacres, and occupation of land resulted in a dwindling population, limited food supply, and traditions at risk. These crises drove tribal leaders to introduce new spiritual customs – the most significant of which was the Ghost Dance.

Wovoka, a shaman of the Northern Paiute tribe, founded this spiritual movement. It became a symbol of hope for all tribes. Wovoka had prophesied the reuniting of all tribes, the banishment of white settlers, and the reintroduction of the wildlife. The Ghost Dance would bring the complete revival of their way of life and unite the ghosts of the ancestors with the living.

The movement became increasingly popular, specifically with the Sioux Lakota tribe. Due to the growing influence of the Ghost Dance across the reservations, the US military became increasingly paranoid.

To establish dominance and to quell support for the movement, police set out to arrest the famous Lakota leader, Sitting Bull. A source notes that this was the largest deployment of federal troops since the end of the Civil War. During a struggle between the police and Sitting Bull’s supporters, he was fatally shot, along with several policemen and supporters. This greatly increased tensions between the government and the Lakota people, especially surrounding the Ghost Dance.

The Massacre at Wounded Knee

There are several accounts of the events that followed the death of Sitting Bull. Some suggest that tribal leader Big Foot was called to the Pine Ridge Agency. En route, he and his 350 followers were intercepted by the 7th Calvary, led by James W. Forsyth.

Others state that Big Foot was advised by local rancher John Dunn to take sanctuary on Pine Ridge.

Once intercepted, Forsyth and his men ordered the Lakota to surrender their weapons. The group was surrounded.

What triggered the massacre is largely debated. Some say that Yellow Bird began performing the Ghost Dance, as another, Black Coyote, was being harassed by the soldiers. Black Coyote, either deaf or unable to understand English, refused to surrender his rifle. Ultimately, a scuffle between Black Coyote and the soldier resulted in the rifle being fired.

“Suddenly, I heard a single shot from the direction of the troops. Then three or four. A few more. And immediately, a volley. At once came a general rattle of rifle firing then the Hotchkiss guns.” –

Eyewitness account from journalist, Thomas Tibbles.

The result was the death of 150 to 300 Sioux Lakota; many unarmed, mostly women and children. The cavalry lost 25 men. The Wounded Knee Massacre was one of the last major confrontations between the US Military and Native Americans.

Medals of Honour vs the End of Resistance

In the days that followed, the Lakota people were buried in a mass grave. Others living at Pine Ridge Academy fled in fear. The Ghost Dance Movement had begun to wither away, and much of the resistance ended. First Nation Americans were now, worse than ever before, forced into reservations or to assimilate into American society. Estimates say that by 1900, only 237 000 Native Americans remained from a population of millions.

Despite the troubling actions of the 7th Cavalry, twenty men were awarded Medals of Honour, the highest commendation of the US Army. Forsyth was later promoted to major general.

‘Medals of Dishonour’

Native American activists, and many others, have labelled these medals ‘Medals of Dishonour’. In 1990, the US Congress passed a formal apology for the massacre. In recent years, however, efforts and pressure by activists have increased. Many argue that rescinding the medals could help mend historical wounds by recognizing the atrocity for what it was.

In February 2021, the South Dakota State Senate unanimously supported a resolution urging Congress to launch a full investigation into the Medals of Honour. Senators Elizabeth Warren and Jeff Merkley co-sponsored the Remove the Stain Act. The act would officially revoke the medals. Further, the names of the recipients would be removed from the Medal of Honour Roll. However, the return of the medals to Congress by surviving family members would not be required.

As the bill was only recently reintroduced, it is unclear whether it will pass through the committee, the Senate, and the House to reach the desk of the President. Tribal council representative for the Wounded Knee District Bernardo Rodriguez believes the bill is long overdue:

“We’ve been pushed, pulled, put aside and treated like second-class citizens since Day 1 and never given a chance,” “I want them to know and to understand that this would be the same as giving a Medal of Honor to the Nazis of Auschwitz.”

Bernardo Rodriguez

According to Kevin Killer, president of the Oglala Sioux Tribe, “History tries to retell it and say there was a misunderstanding, but it was an atrocity any way you look at it.”

A series of events damaging the cultural traditions and population of Native American people in the 19th century culminated in this massacre, the last major conflict of the American Frontier Wars. The Remove the Stain Act, a bill that would rescind the twenty Medals of Honour, is aiming to rectify history, correct the wrongs of the past, and help the survivors move forward.