Reading time: 6 minutes

Since the election of Joe Biden and Kamala Harris, journalists, scholars, and activists have celebrated Harris as the first vice president who is a woman and of Asian American and African American heritage. She is not, however, the first person of color to hold the office. For many people, this comes as a surprise. However, for scholars of Native American and Indigenous Studies (NAIS), as well as many US historians whose work focuses on the executive branch of the federal government, Charles Curtis’s name is already well-known. Curtis, a member of the Kaw Nation and the first person of color to serve as vice president, is suddenly a figure of popular interest.

By Kiara M. Vigil, Amherst College.

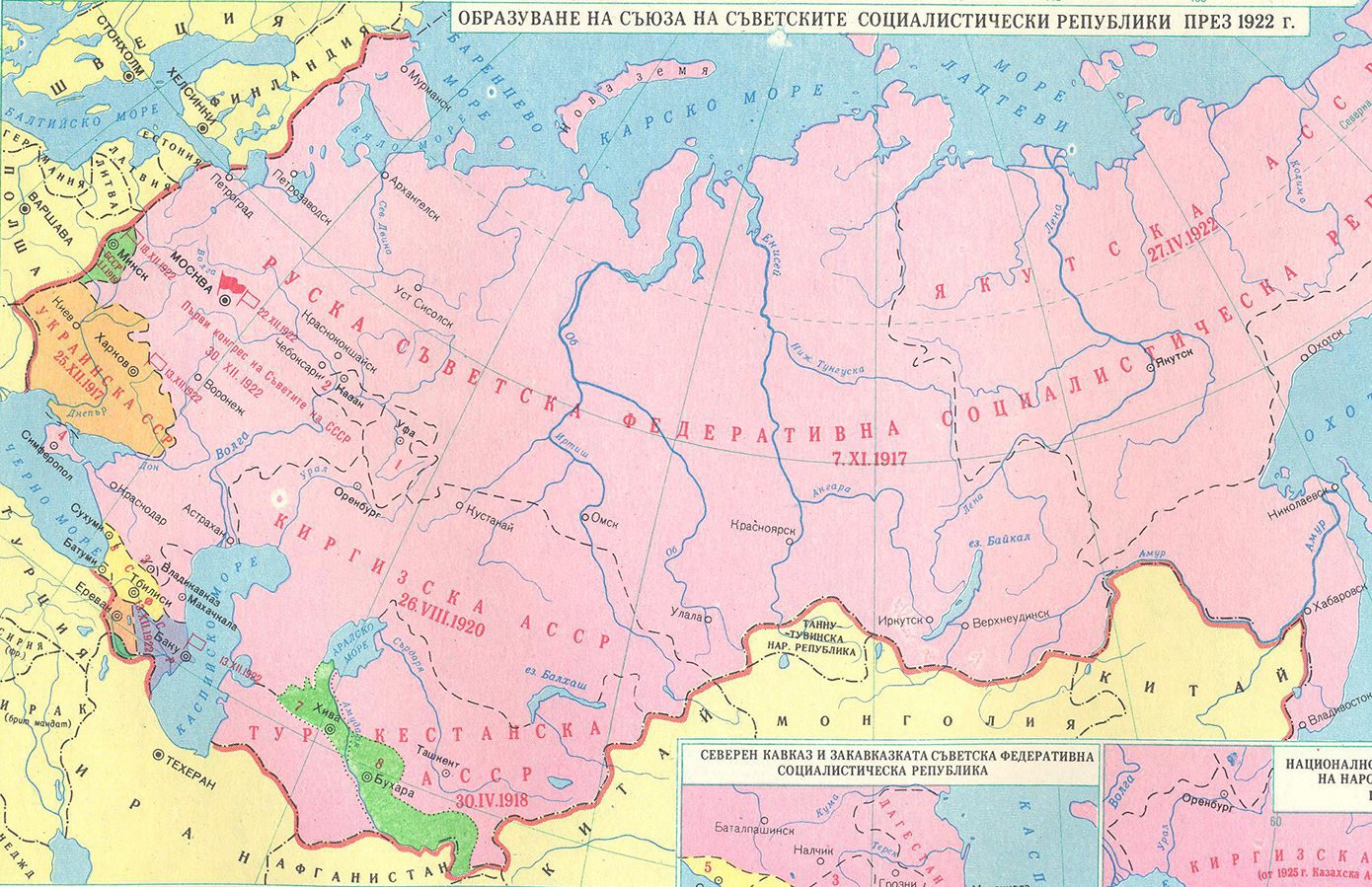

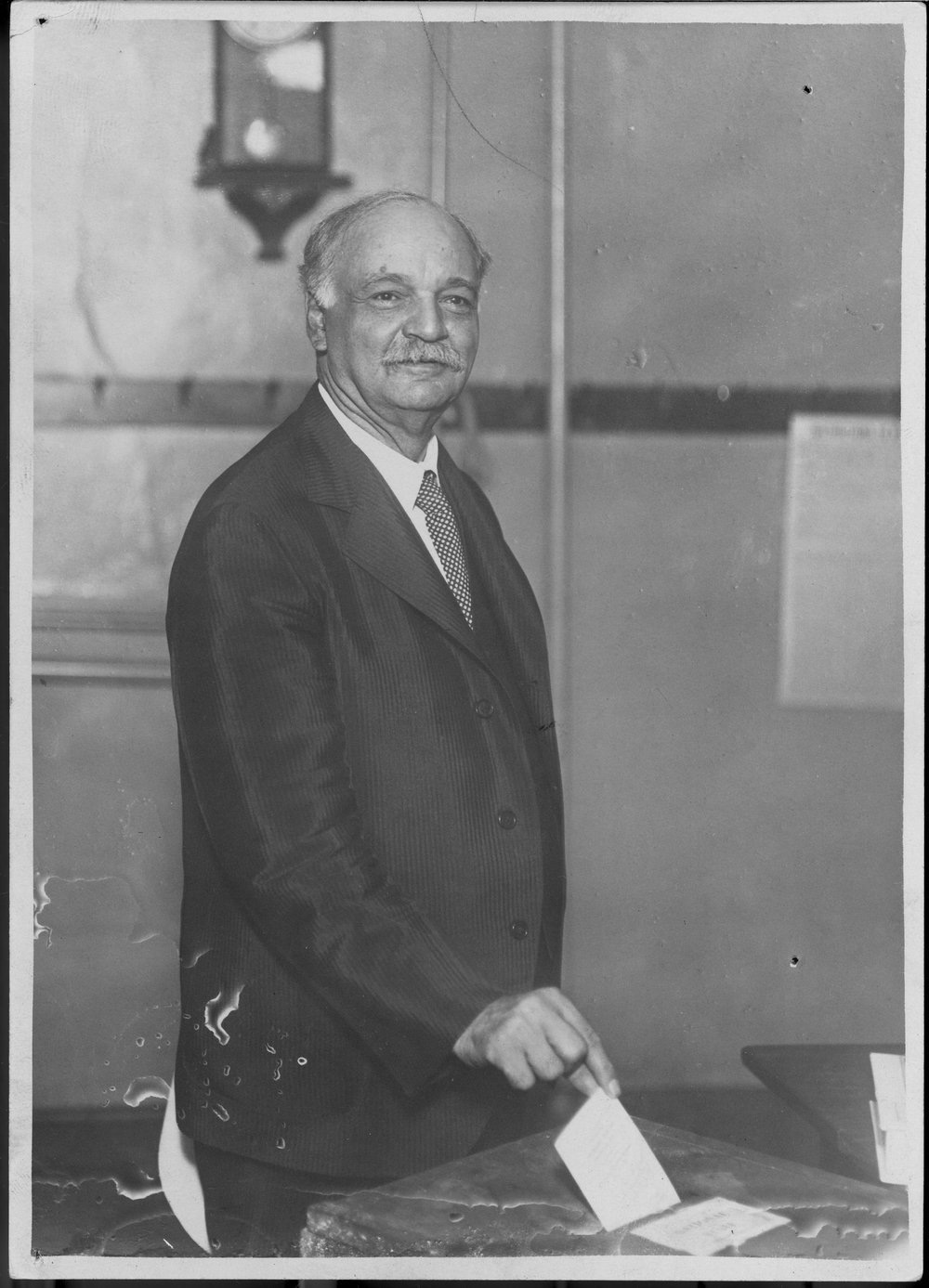

Vice President Charles Curtis (1860-1936) casts a vote in the US Senate in 1929. kansasmemory.org, Kansas State Historical Society, Copy and Reuse Restrictions Apply

Born in 1860, Curtis was proud of his Kansas roots, as is clear from his personal papers located in the Kansas Historical Society. He grew up speaking both Kansa and French, before he learned English, and he remained close to his Indigenous relatives and the Kaw nation. Curtis may be most notable for his political career, which spanned six terms as a congressman (1892–1907) and 20 years as a senator (1907–13, 1915–29), where he served as the Republican Party whip and majority leader. In 1928, he was elected as Herbert Hoover’s vice president.

Curtis’s most lasting legacy, certainly for scholars of American Indian history, is the Curtis Act. The 1898 Curtis Act amended the Dawes Act of 1887, which gave the federal government the power to break up tribally held lands. Most federal Indian policy officials interpreted this law as dismantling Indigenous claims to communally owned land and encouraging the incorporation of Native people into American society by incentivizing “improvements” they made to the land allotted to them. Any “surplus” land—which was not allotted to tribal people—was available for sale to non-Natives. Before any of this newly private property was allotted, the government created a process by which it would determine which Native people were eligible to receive land. This resulted in the creation of a federal definition for Indian identity, a policy that extended the federal government’s interventions into the lives of Native people as its perceived “wards.”

Twelve years later, the Curtis Act extended allotment to the Five Tribes—the Choctaw, Chickasaw, Cherokee, Muscogee (Creek), and Seminole living in Oklahoma—who had been exempted from the 1887 act. As a Kansas representative in Congress and a Kaw citizen, Curtis authored the law, which was officially titled “An Act for the Protection of the People of Indian Territory, and For Other Purposes.” The title embodies a paternalistic discourse that pervaded federal Indian policy at the time. Despite his name being attached to it, Curtis wrote in his autobiography about being unhappy with the final version. He had hoped it would be better than the Dawes Act, which he criticized for abrogating time-honored treaties, and that his act would do more to help Native nations transition to a system of private land ownership. Instead, it was far more radical as it abolished tribal courts and instituted civil governments in an attempt to merge Indian territory with the new state of Oklahoma. Cherokee leader Robert L. Owen, president of the First National Bank of Muskogee, objected to the Curtis Act for trying to destroy tribal governments in the Indian Territory.

Curtis’s most lasting legacy, certainly for scholars of American Indian history, is the Curtis Act.

Despite Curtis’s own connections to his Kaw, Potawatomi, and Osage relatives, the Curtis Act, like the Dawes Act before it, increased settlement by white Americans on Indian lands, further dispossessed Native people, and weakened or dissolved tribal forms of governance. Before 1896, the Five Tribes “had exercised sole jurisdiction“ over citizenship requirements for each of their nations. With the Curtis Act, the federal government now decided who was eligible for tribal citizenship, which furthered the disenfranchisement of Black freedmen who were members of these tribal nations. Today, NAIS scholars and Native people recognize the Curtis Act as a critical turning point in the history of tribal sovereignty.

As individual Natives struggled to make a living with their allotments, Curtis still favored certain aspects of “assimilation.” He believed Indigenous people would only survive colonization by pursuing American education and incorporating themselves into American institutions, while managing to retain parts of their Native identity. He thought his own life was a testament to such a strategy. Curtis believed that this sort of incorporation was the future for Native Americans given the increasing power of the US federal government in the realm of Indian affairs.

Curtis was a complicated figure. He felt at home among his Kaw family as well as in the halls of Congress. He maneuvered through a settler state that continued to erase Indigenous claims to sovereignty over land, politics, and culture at every turn. It is too facile to write off Curtis as an assimilationist, because he lived during a time in which many Indigenous intellectual leaders struggled with which aspects of American culture they wanted to incorporate into their lives and which to challenge, rewrite, and reimagine. Although his views on assimilationist legislation became more critical by the mid-1920s, Curtis largely accepted the dominance of white settler society.

Curtis maneuvered through a settler state that continued to erase Indigenous claims to sovereignty over land, politics, and culture at every turn.

While Curtis pushed for assimilation as a member of the American government, he did not represent the Kaw Nation. Throughout the 20th century, many Kaw Nation citizens resisted the encroachment of mainstream America into their lives by continuing their traditions, especially in the face of schooling that did not allow their children to speak their native language. Today, the Kaw participate in an annual powwow and other ceremonial activities aimed at cultural revitalization and have found economic opportunities through a casino and tobacco shops, enabling them to create social service programs and offer emergency assistance and academic scholarships to their citizens.

Curtis’s legacy is ripe with complexity and contradiction. A man who sometimes voted against the best interests of his fellow Indians also achieved a great deal at a time when the odds were against him. The racial and cultural politics of the 1920s, a time in which the second iteration of the Ku Klux Klan emerged, were easily as fraught as they are today. His legacy remains slightly unsettling and even mysterious, his place in history unprecedented. Now with the inauguration of Kamala Harris as vice president, there will be another first in American history.

This article was originally published in Perspectives on History.

Podcasts about Charles Curtis

Weekly History Quiz No.229

1. In which year was the Battle of Long Tan?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

The text of this article is republished from Perspectives on History and is is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.