Reading time: 4 minutes

Diwali is a festival of lights and celebrates the triumph of light over darkness – but where does this stem from? Suzanne Newcombe looks at the religious festival’s origins in this article.

By Suzanne Newcombe, Open University

Lights illuminating the darkness, merriment, and promoting future good fortune are central to the Indian festivals widely celebrated in the middle of the Indian month of Kartik (which crosses the end of October and the beginning of November).

Diwali – also called Deepavali – is an ancient festival, with early written references found in several Puranas (ancient Hindu texts) dating to early in the common era, though the origins of the festival are even older. The root meaning of the word Diwali is the Sanskrit Deepavali, made up of deepa (which can refer to lamp, light or illumination; or knowledge) and avali (a row or series). This celebration has a wide range of narrative explanations across India – being a time of celebration for Hindus, Sikhs, Jains and even some Buddhists. The celebrations span over several days, and different communities take different central days for the focus of their festivities.

Rama and Sita, with Lakshmana returning to Ayodhya, artist unknown, 17th-18th century, National Museum, New Delhi, Accession Number: 51.65/74

Perhaps the most dominant story associated with Diwali is a celebration of when Rama, Sita and Lakshmana returned to their home of Ayodhya, after defeating Ravana and at the end of their 14-year exile, a story found in the enormously popular epic poem, The Ramayana. However, in Southern India this festival is more closely linked with a story about Krishna and his wife Satyabhama killing the demon Narakasura. Jains believe that during this period the Jain tirthankara (‘ford maker’/spiritual teacher) Mahavira attained moksha (spiritual liberation) in the sixth century BCE and many Jains also participate in ritual worship of the goddess Lakshmi during this period. For Sikhs, this festival coincides with an important historical event: when the sixth Sikh Guru Hargobind Singh was released from prison in 1619 by the Mughal emperor Jahangir. Different elements of celebration have been added over time or are central to specific communities – giving sweets, buying new clothes and gambling are some examples.

There is no surprise that in Britain the celebrations of light and fireworks fit nearly seamlessly into the more ‘native’ British traditions around the beginning of the darkest season of the year known as Samhain and the more recent tradition of fireworks on ‘bonfire night’. Celebrations for Diwali are particularly large in UK cities which have many people from Indian backgrounds including Wolverhampton, London, Leicester, Edinburgh, Birmingham and Belfast.

Radha and Krishna watching fireworks in the night sky by Sitaram. Kishangarh, late 18th-century, National Museum, New Delhi

Although being associated most strongly with Hinduism, the festival has traditionally been an occasion for intra-faith festivities, with some Christians and Muslims joining in the celebrations as well. There are testimonials during the Mughal rule of Northern India which show that both courts and common Muslims engaged with widespread festivities at this time, termed Jashn-e-Chiraghan, under the third Mughal emperor Akbar who ruled from 1556 to 1605. In another example, the Catholic Church in Goa issued a statement asking Christians to explore the rich symbolism and meaning of the festival in 2022.

For many who celebrate Diwali its central message is one of hope – to celebrate the power of light to triumph over darkness, and knowledge to conquer ignorance.

This article was originally published in The Open University.

Podcasts about Diwali

Articles you may also like

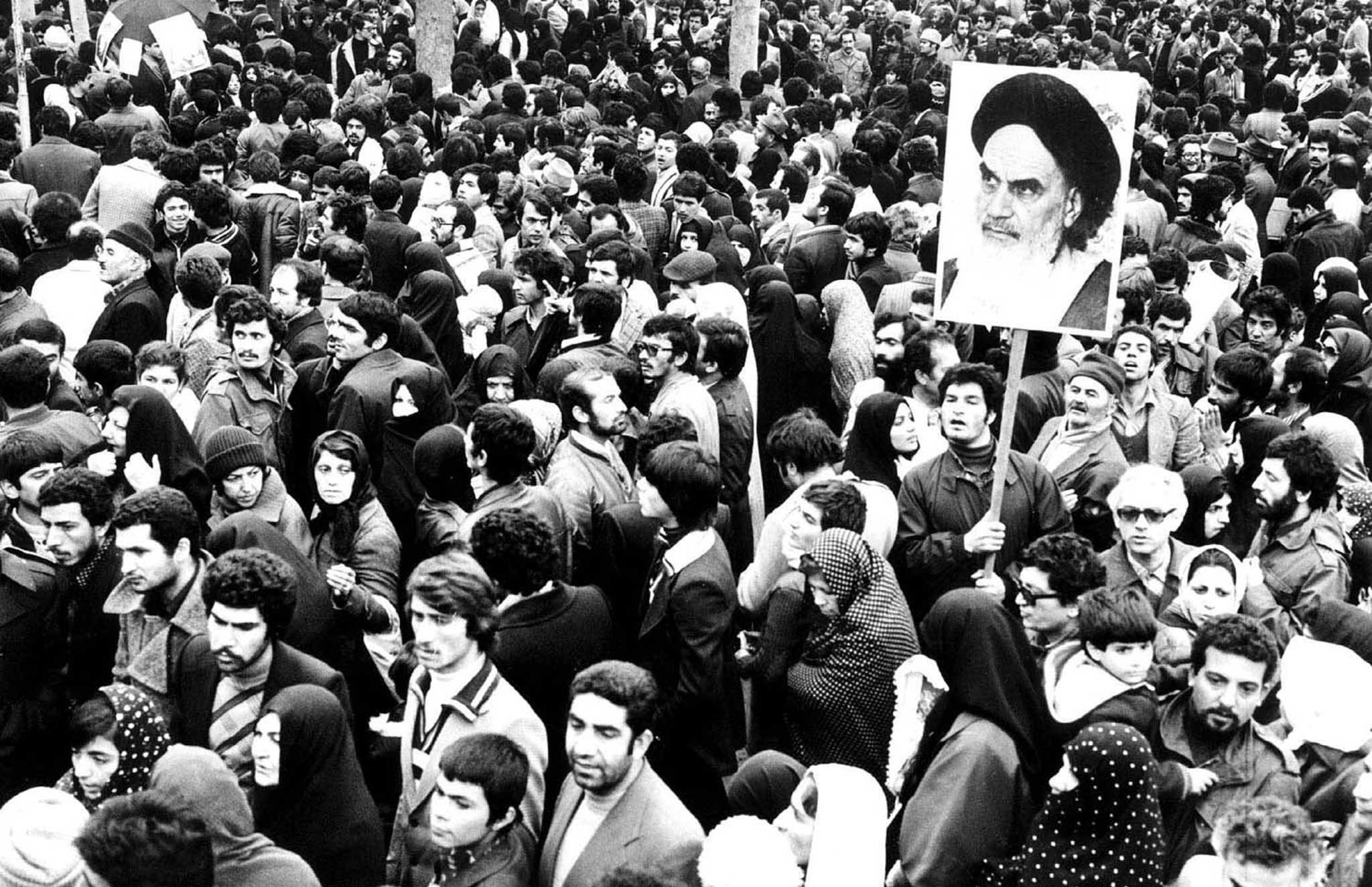

The Iranian Revolution

To understand what caused the Iranian Revolution, we must first consider the ongoing conflict between proponents of secular versus Islamic models of governance in Muslim societies. It all began with the British colonisation of India in 1858, which precipitated the collapse of classic Islamic civilisation. By early 20th century, almost the entire Muslim world was colonised […]

Why there is no Kurdish nation

Reading time: 6 minutes

In a series of conferences in a succession of European palaces, Prime Minister David Lloyd George, Georges Clemenceau of France, Woodrow Wilson and dozens of other leaders conspired, harangued and horse-traded from 1919 to 1921. Under clouds of cigar smoke, between servings of foie gras and champagne, they redrew a large swath of the globe’s map.

Their guiding principle for redrawing the map, at least in most cases, was the reigning concept of race nationalism, what’s often called today ethno-nationalism.

Broodseinde Ridge – Podcast

On the back of the victories of Menin Road and Polygon Wood, the 1st Anzac Corps pushed on towards the dominating feature of Broodseinde Ridge. This time though, they would have the men of the 2nd Anzac Corps fighting alongside them. The Battle would see the Allied troops looking down upon green pastures for the first time in three years, bringing hope that the war may soon be over.

The text of this article is republished from The Open University and is is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.