Reading time: 5 minutes

Alongside much else that is being revised, reimagined or recast by the Albanese government, Australia is to have a new cultural policy. Consultation has involved town hall meetings and a call for submissions. The arts minister, Tony Burke, has established five review panels to consider feedback.

First Nations artists and culture are at the centre of Burke’s invitation. The emphasis on the artist not just as creator but as worker responds to the pandemic’s devastating impact on the already-parlous circumstances in which artists and writers often live and work.

By Michelle Arrow (Macquarie University) and Frank Bongiorno (Australian National University)

The other pillars of this cultural-policy-in-the-making highlight the diversity of stories and artists, building audiences and the strengthening of cultural institutions.

The review panels are brimming with respected and innovative creators and producers, with decades of collective experience.

But their coverage of the sector is patchy. Our concern as historians is with history, publishers and the “GLAM” sector – galleries, libraries, archives and museums.

While there is representation from galleries and collecting institutions on the panels, there is not a single historian, publisher or archivist whose feedback will help shape Australia’s cultural policy.

Given the importance of history in defining our sense of national selfhood, and the role publishers, libraries, archives and museums play in preserving, collecting and presenting Australian histories and stories, these fields being absent from the national cultural policy panels is a disappointing oversight.

A sense of belonging

History and historians play a crucial role in Australian culture. They are foundational to other fields in the arts, with historical research often underpinning film, theatre, literature and even, on occasion, dance.

A government serious about implementing a cultural policy for the future must make space for history and historians in the formulation of that policy.

History is both a scholarly pursuit and a widely shared leisure activity. Millions of Australians visit museums, archives, libraries and galleries each year, both in person and online.

Family history has become much more than just a popular hobby. It is integral to people’s sense of self and belonging, with First Nations people and migrant communities increasingly active.

Australians are involved in history and heritage in their communities. These activities are integral to identities of people and places, and especially regional places. They keep people active and connected with one another.

Community history and heritage needs to be at the heart of a democratic and inclusive cultural policy.

The place of history

Historians feature in our media as expert commentators. They speak at writers’ festivals and in documentaries.

They publish histories and biographies that attract readers outside the circle of their colleagues and students. Some make podcasts and television programs.

Historians provide policy advice to government. They judge literary prizes and contribute to the making of the school curriculum. Historians work with community groups, including with Indigenous communities in native title cases, and they advise on cultural heritage.

The Prime Minister’s Literary Awards include a dedicated prize for Australian history. History is one of five subjects mandated in the national curriculum. Days of national commemoration, from Sorry Day to Anzac Day, mark significant events in Australia’s collective national memory.

Both state and Commonwealth governments fund institutions which collect and preserve Australian history. At the federal level, the national cultural institutions perform this work. Together with the public broadcasters the ABC and SBS, they represent a priceless possession of the nation.

Writing and knowing Australian history would be impossible without them, and we would be a different – and lesser – people without such places.

Struggling institutions

Governments from both sides of politics have subjected these institutions to humiliating funding cuts. Labor first created “efficiency dividends” to reduce expenditure on our national cultural institutions in the late 1980s.

This initiative meant that every year, they received less funding, which a 2019 parliamentary business committee found had a “significant and compounding effect”.

It got worse in 2015-16, when the Turnbull government disastrously imposed an additional 3% “efficiency target” on these cultural institutions.

Such funding cuts no longer drive “efficiencies”. They diminish the quality of the user experience. Researchers at the National Archives report long delays – sometimes years – in gaining access to records that under the law of the land are supposed to be made available within 90 business days.

Our national cultural institutions no longer have sufficient funds to preserve the collections they maintain on our behalf.

The Archives only received an urgent injection of funds to preserve unique audio-visual records after a public campaign in 2021.

In June, it was reported the maintenance backlog at the National Gallery of Australia is estimated to be A$67 million. The ABC recently announced plans to slash specialist archives and librarians.

Cuts to funding came with the leaching of historical expertise from the boards and councils established to advise the national cultural institutions.

In the past, many distinguished historians have served on these bodies. Today, they are more likely to be defined by political appointees.

As Tony Burke commented recently:

I don’t see how you have a national museum with a board that does not include a single historian.

Neither do we. We further urge a stronger presence for history in cultural policy generally – and right now for the presence of historians in the constructing of a new policy document.

History is the very kind of creative and democratic practice that must be central to any reimagining of Australia in an age of anxiety and of promise.

Podcasts about Australia’s new cultural policy:

Articles you may also like:

Cuba without Fidel: Five Years Later

Reading time: 6 minutes

For nearly 60 years, and for better or for worse, Fidel Castro was Cuba; at least he fancied himself as such, and the Communist Party which he largely governed with total control, never questioned this image. But what about the Cuban people? Did they really view Fidel as a “modern day Simon Bolivar”, and their one defender against American imperialism?

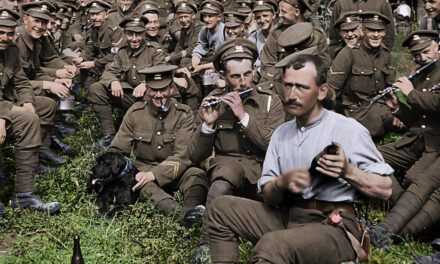

The First World War continues: Medina, Arabia, January 1919

Reading time: 6 minutes

or many in the West, the First World War in the Middle East was a sideshow to the Western Front. The story of the wartime siege of Medina is even less well-known. But in the region it is still debated and contested, for example in December 2017 when the Foreign Minister of the United Arab Emirates accused Fakhri Pasha of stealing items from Medina, which earned a strong rebuke from the President of Turkey. The First World War in the Middle East had a profound effect on the region, with consequences to this day.

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.