Reading time: 5 minutes

Barrow Island, located 60 kilometres off the Pilbara in Western Australia, was once a hill overlooking an expansive coast. This was the northwestern shelf of the Australian continent, now permanently submerged by the ocean.

By Peter Veth, David W. Zeanah, Fiona Hook, Kane Ditchfield, and Peter Kendrick (University of Western Australia)

Our new research, published in Quaternary Science Reviews, shows that Aboriginal people repeatedly lived on portions of this coastal plateau. We have worked closely with coastal Thalanyji Traditional Owners on this island work and also on their sites from the mainland.

This use of the plain likely began 50,000 years ago, and the place remained habitable until rising sea levels cut the island off from the mainland 6,500 years ago.

A unique time capsule

The northwestern shelf and the submerged coastlines of Australia are immensely significant for understanding how and where First Nations people lived before and during the last ice age.

When the last ice age was at its coldest (24,000 to 19,000 years ago), sea levels worldwide were about 130 metres below current levels. As the ice melted, the sea rose rapidly, eventually flooding the connection between Barrow Island and the mainland.

Since Aboriginal people did not occupy the island after this time, the human archaeological record of Barrow Island is a time capsule, unique in Australia. Most other coastal occupation areas from this period are now beneath the sea, but these drowned landscapes were once vast and habitable.

The largest rock shelter on the island is Boodie Cave, one of Western Australia’s oldest archaeological sites. Excavations here revealed evidence of Aboriginal occupation dating back at least 50,000 years.

As sea levels fluctuated through time, the distance from Boodie Cave to the seashore varied significantly. Aboriginal people brought shellfish back to Boodie Cave even when it was many kilometres from the coast.

As the sea rose, people’s diets changed. The quantity of shellfish, crabs, turtles and fish consumed in the cave increased through time.

Aboriginal people here mainly used local, silica-rich limestone for crafting their stone tools. While this material was readily accessible, it blunted easily. Instead, people used thick and hard shells from large Baler sea snails to make knives for butchering turtles and dugong.

43,000 years of exchange

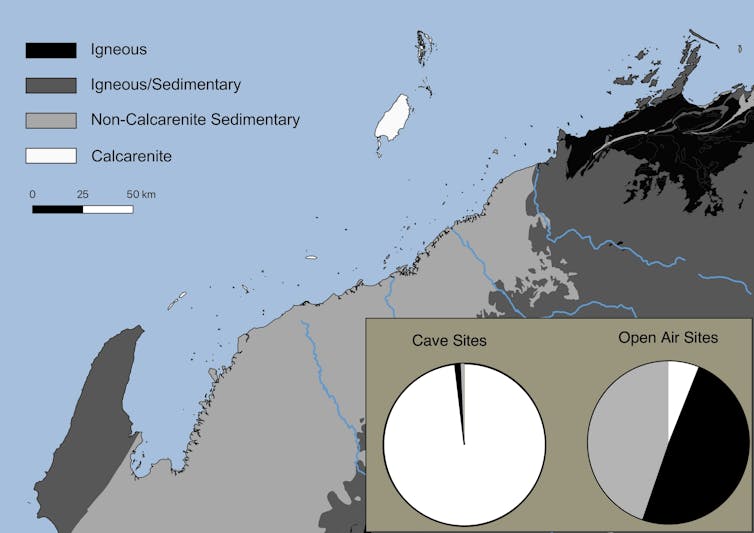

In contrast to the cave deposits, the open-air archaeological sites present a different picture. Three years of systematic field surveys recorded over 4,400 flaked and ground stone artefacts from nearly 50 locations.

Excluding one limestone source, most of these stone tools represent geological sources not found on the island. This means they were made out of rocks more typical of the west Pilbara and Ashburton regions.

The artefacts we’ve found on Barrow Island show that Aboriginal people transported and exchanged stone materials from inland or places now under the sea for over 43,000 years.

We don’t yet know why the artefacts in the cave are so different to the ones found in the open air.

The numerous open sites leave a record of how Aboriginal people adapted to sea-level changes. Both the surface and cave records suggest that Aboriginal people used more local limestone and shell tools as rising sea levels cut off access to the mainland or drowned sources.

Imported stone tools were precious and therefore conserved and heavily used for grinding seeds, working harder materials such as wood, and likely for cutting softer materials such as skins and plant fibre.

While early Aboriginal people continued to use coastal resources, they maintained social networks and exchanges with the mainland. The open sites from Barrow Island provide one line of evidence connecting contemporary Aboriginal people to the now-drowned coastal plains, coastlines and continental islands.

An ancestral connection for Thalanyji peoples

Despite the distance of Barrow Island from the mainland for most of the last 6,500 years, Thalanyji knowledge holders refer to the use of the island from both historic-era fishing activities and as forced labourers in the early pearling industry.

They know the Sea Country between the islands, and the songline connections linking the mainland to the islands. Traditional Owners involved in our project see the artefacts as evidence of their ancestral connection to the island, old coastlines and now drowned coastal plain.

The Barrow Island open-air sites are a significant time capsule, offering unique insights into coastal Aboriginal lifeways over tens of thousands of years.

These sites, combined with the cave records, provide scientists and Traditional Owners with invaluable opportunities to understand and preserve Australia’s rich and deep history.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Articles you may also like

The Australian Flying Corps, 1917–18

THE AUSTRALIAN FLYING CORPS, 1917–18 By 1917, the men of the Australian Flying Corps’ No. 1 Squadron had been fighting in the Middle East for almost two years. Now Australia’s airmen were ready to join the allies’ broader campaign in the Great War. By Alan Stephens Because Europe was the main theatre, the next three AFC […]

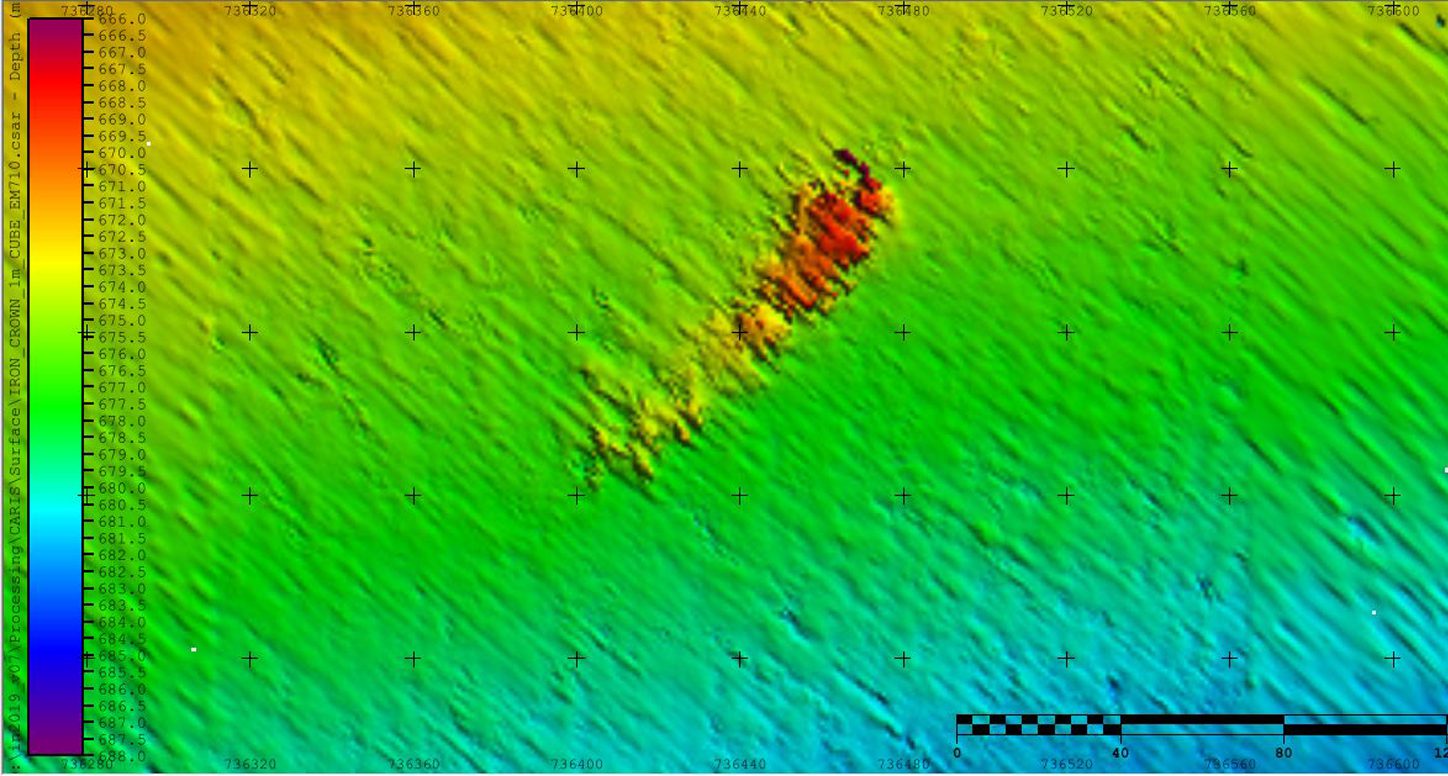

What happens now we’ve found the site of the lost Australian freighter SS Iron Crown, sunk in WWII

Reading time: 6 minutes

Finding shipwrecks isn’t easy – it’s a combination of survivor reports, excellent archival research, a highly skilled team, top equipment and some good old-fashioned luck.

And that’s just what happened with the recent discovery of SS Iron Crown, lost off the coast of Victoria in Bass Strait during the second world war.

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.