WALKING WITH THE DIGGERS

Reading time: 5 minutes

The Centenary Commemoration of the Great War continues to unearth real treasures from our military history, none more mesmerising than this Exhibition of photographs taken by Australian Diggers, Sailors and Airmen in most theatres of the First World War.

This collection hasn’t been abroad for some 90 years. Originally, it was part of a 1920s exhibition entitled The Pictorial Panorama of the Great War, then the photographs appear to have languished in storage.

What makes this collection so extraordinary is that the photographs have been colourised, by hand, by Colarts Studios in Melbourne in the twenties. The Studios, founded by Captain William Joynt VC, and employing ex-service personnel, did a superb job, both nuanced and careful, and the resulting photographs come vividly to life.

Time travel is impossible but this exhibition is the closest possible experience to walking with the Diggers, from ANZAC Cove to Armistice Day, in Cologne, Germany, across the ruined battlefields of Europe and the scorching plains of the Middle East, from aerial dogfights to the pursuit of U-boats.

Elise Edmonds, the NSW Library’s chief curator and her team have accomplished much, bringing to Australia 2016 the most significant collection of Great War photographs since the Australian War Memorial staged the ‘Lost Diggers of Vignacourt’, supported by the philanthropy of Kerry Stokes.

Travelling the battlefields of the Great War now, it’s striking to experience just how small some of the famous landmarks happen to be. Anzac Cove, at Gallipoli, for example, is little more than a postage stamp, overwhelmed by looming cliffs, on the edge of the peninsula. How allied forces were ever going to be able to cut across the peninsula, in the face of strong and determined Turkish resistance and in hostile terrain, is an unanswered and unanswerable question.

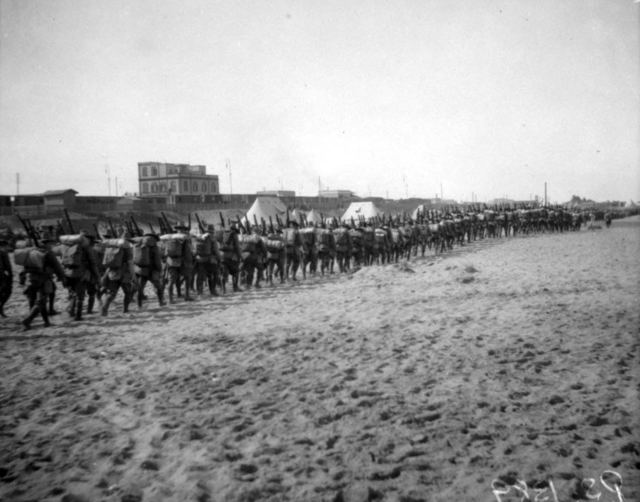

The photographs of the beachhead, mostly taken by anonymous diggers and some delicately censored, to preserve the modesty of naked bathers, brings that home in a sharp and unambiguous fashion. You stand on the beach, in sunshine and rain, surrounded by stores and materiel, looking out to the piers, all within Turkish artillery range.

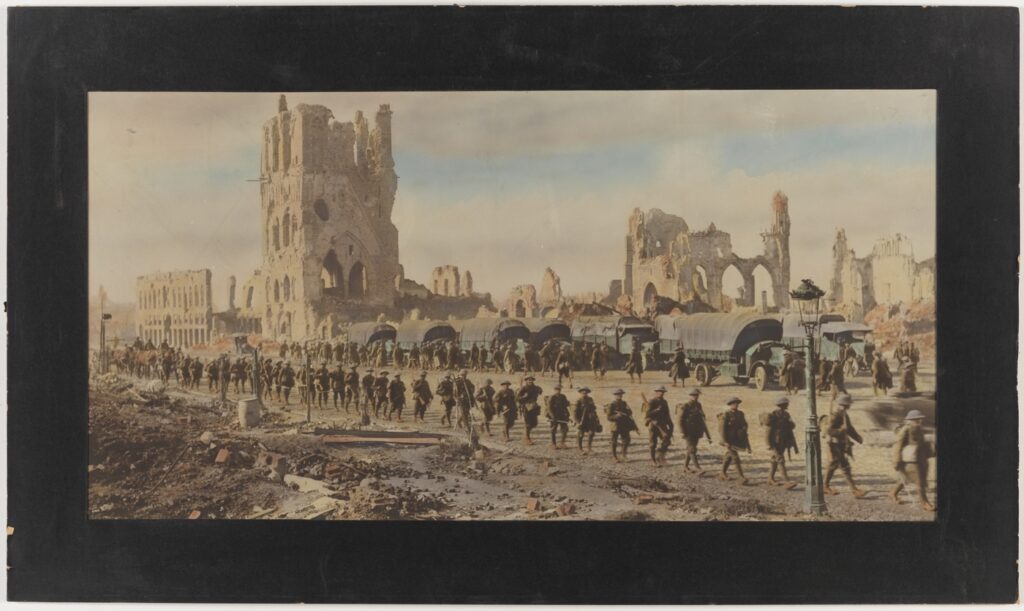

It’s German artillery however, which has wrought the most awful damage upon the communities of Belgium and France. The destruction of factory and farm, city and community is truly dreadful, faithfully recorded by Australians passing through or in the trenches.

The work of the great Australian wartime photographer, Frank Hurley, is in evidence but the photographs taken by nameless Diggers are often equally poignant and persuasive reminders of the horrors of the Great War.

What emerges clearly is the determination of the Australians to tell the home front just what the War was really like. Shattered villages; desolate roads or a lone cross on an Australian gravesite convey terrible truths, without filter or sentiment.

What’s also clear is that Australians after the War, who visited The Pictorial Panorama of the Great War, were keen to see just where their men and women in uniform had been while abroad. The curiosity of the Diggers was matched by the interest at home.

Australian soldiers on the Western Front weren’t permitted (officially) to have the improving technology of the camera. Quite obviously, that rule was observed in the breach, and we may all be grateful for this reality.

Some photos have been carefully, almost seamlessly stitched together, to provide sweeping vistas of battlefields or dogfights in the air or the destruction of entire communities.

The captions, too, are worthy of note for they’re often original. The German opponent is routinely described as ‘The Hun’. He’s usually shown in adversity, as a prisoner or in retreat in the air or under attack at sea.

A typical caption on a photograph of German prisoners of War carrying a wounded soldier during a gas attack runs:

‘Gas About. Hun prisoners bringing wounded down the east-west road opposite Villers- Bretonneux, August 1918, during the attack on Proyart’.

There was no doubting attitudes towards the enemy after four long years of sacrifice and slaughter.

Yet the photographs of Australians in Cologne after the Armistice of November 1911 are characterised by light hearted good humour. Cologne, which was occupied by the New Zealanders, was off-limits to Australians. Appropriately, blessed by two Australian Army padres the Australian men and women are cheerfully disobeying General Haig’s orders (again!). By the way, have a close look at two of the Australian Diggers, they’re mere boys.

This exhibition shouldn’t be missed by anyone interested in our military history, particularly of the Great War. It’s magnificent in its dimensions and is a brilliant historical record of our service to the Allied cause and ultimate victory in 1918.

This article was originally published in The Strategist.

Articles you may also be interested in

General History Quiz 71

Weekly 10 Question History Quiz.

See how your history knowledge stacks up!

1. What aircraft is this?

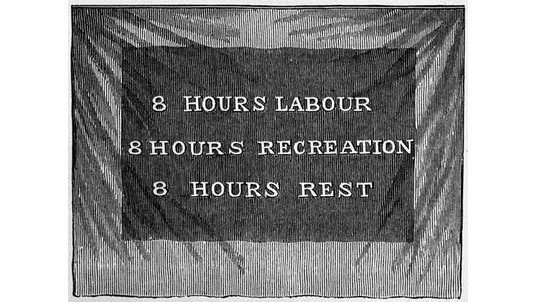

Why Do We Have an 8-Hour Working Day?

Reading time: 3 minutes

The working day as we now know it was the result of international, cross-industry labour efforts from workers, unions and activists, spanning well over a century of campaign, unrest and even death. The Industrial Revolution, with the spread of electrical lighting and extremely low hourly wages, had ended the traditional, rural working patterns of sun up to sun down, and meant that in some industries workers were forced to endure up to 18-hour shifts.

The text of this article is republished from The Strategist in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.