Reading time: 7 minutes

The emotive styles captured both the physical destruction of war to humanity and the environment and its lasting emotional toll.

By Madison Moulton

World War I, the first truly global conflict, impacted every facet of society and culture, including the art sphere. New forms of weaponry, casualties on an unbelievable scale, and changing political structures drastically reshaped the world and formed a new cultural landscape.

Artists who experienced firsthand or observed the change (in the case of commissioned war artists) channelled their grief into a range of evocative artworks that remain recognized and appreciated to this day.

Firmly in the modern art period, experimentation in expression at this time was prominent, producing dramatic artworks that in some ways challenged the conventions of previous schools (although not always). The emotive styles captured both the physical destruction of war to humanity and the environment and its lasting emotional toll. These six artworks depict the horrors of WWI in haunting detail.

Gassed by John Singer Sargent (1919)

Painted shortly after the war, Gassed is one of the most well-known artistic records of the conflict. One of several artists commissioned by the British War Memorials Committee, American painter John Singer Sargent travelled to the Western Front to witness the realities of warfare in Arras, France and Ypres, Belgium. In this monumental canvas, he portrays a line of wounded soldiers with eyes bandaged and hands on one another’s shoulders, blinded by gas and cautiously stepping forward above piles of bodies.

Sargent’s work is striking for its subject but also for its sheer scale: the painting itself is around 6.1m by 2.3m, with the figures almost life-sized. The arrangement of the figures and the colors used conveys the devastation of chemical weapons, one of the major characteristics of the First World War. It was voted picture of the year by the Royal Academy of Arts in the same year and remains one of the most prominent works depicting the war.

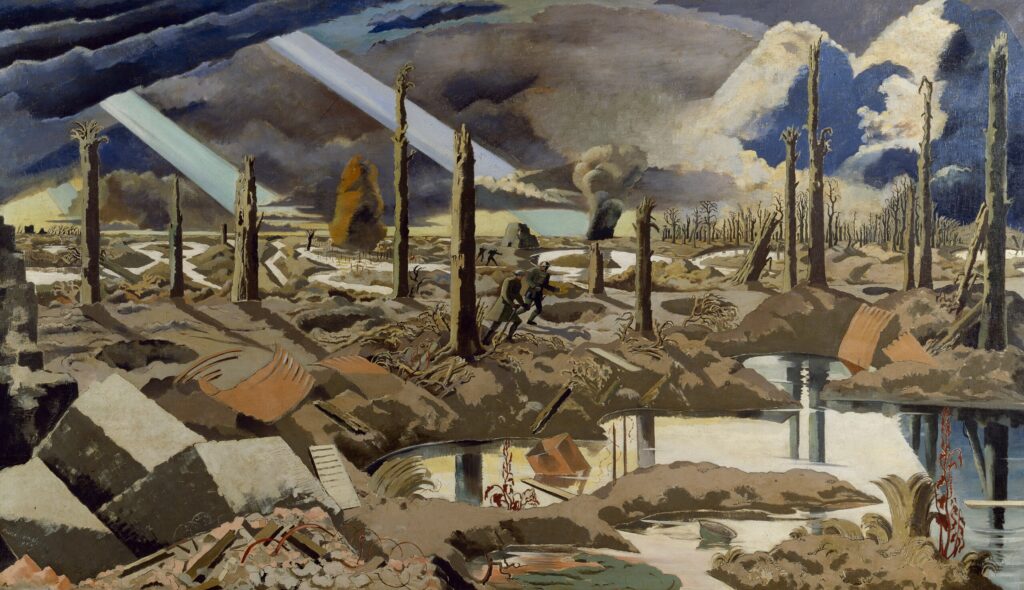

The Menin Road by Paul Nash (1919)

British artist Paul Nash was also commissioned by the British War Memorials Committee along with Sargent and his brother John Nash. Although known as an official war artist, Nash was a soldier himself too, part of the Hampshire Regiment sent to the Western Front in 1917. In The Menin Road, he depicts a gloomy war landscape covered in smoke. The foreground highlights flooded trenches and stray remnants of machinery, framing a few soldiers navigating their way through destroyed trees.

An iconic image of the Great War, the neutral colors and block-like forms characteristic of the period convey a sense of loss and destruction. While there are human figures, they are neither detailed nor the focus of the painting. Instead, the ruined environment becomes the subject, conveying the wider impacts of battle. Like Gassed, part of the impact of this painting is its size, measuring 3.1m long and 1.8m wide.

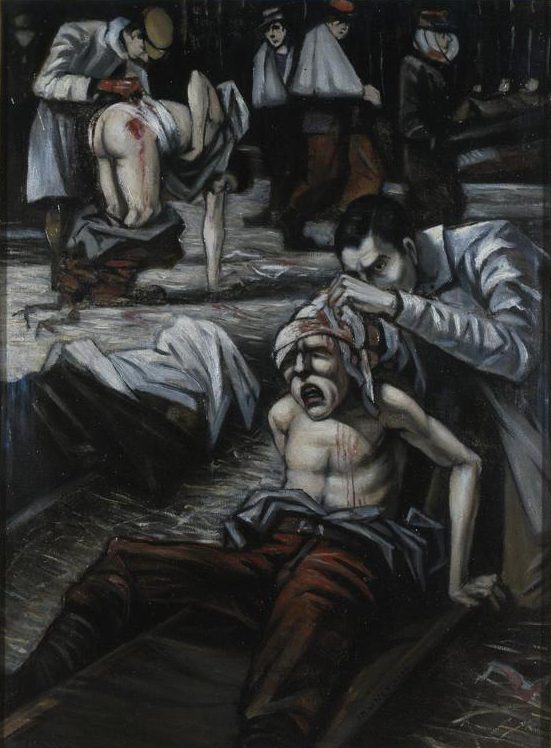

The Doctor by CRW Nevinson (1916)

C.R.W. Nevinson’s The Doctor offers a slightly different perspective, focusing on individual figures. That’s not to say he didn’t cover broader scenes, like in The Harvest of Battle (1918) and Paths of Glory (1917), but this piece deserves mention for highlighting the experiences of the wounded and the medics who helped them during the war.

Nevinson spent nine weeks in 1914 working at Dunkirk in a goods yard that housed thousands of wounded troops. He used this experience to create The Doctor, depicting medics treating anguished wounded soldiers. Next to the figure in the foreground, a body lies covered in bandages, while another doctor treats a soldier in the background. The painting provides a closer look into the real experiences of medical teams during the war.

The Funeral (Dedicated to Oskar Panizza) by George Grosz (1917-1918)

The previous works have all depicted the war directly. The Funeral does not, but does capture the dark mood of the period, shaped by societal awareness of the horrors of war. George Grosz’s work displays elements of his feelings toward war, corruption, and what he saw as the moral decay of German society during and after World War I. It is reminiscent of medieval hellscapes, featuring icons of death and mobs of crazed people.

The many figures in the scene blend together with twisted faces, surrounding a skeleton (representing the Grim Reaper) sitting on a coffin. Buildings lean and create a claustrophobic atmosphere full of chaotic energy. While thematically it might differ from other war paintings (as it doesn’t depict the front lines), it shows that the terrors and impact of WWI were not limited to the battlefield.

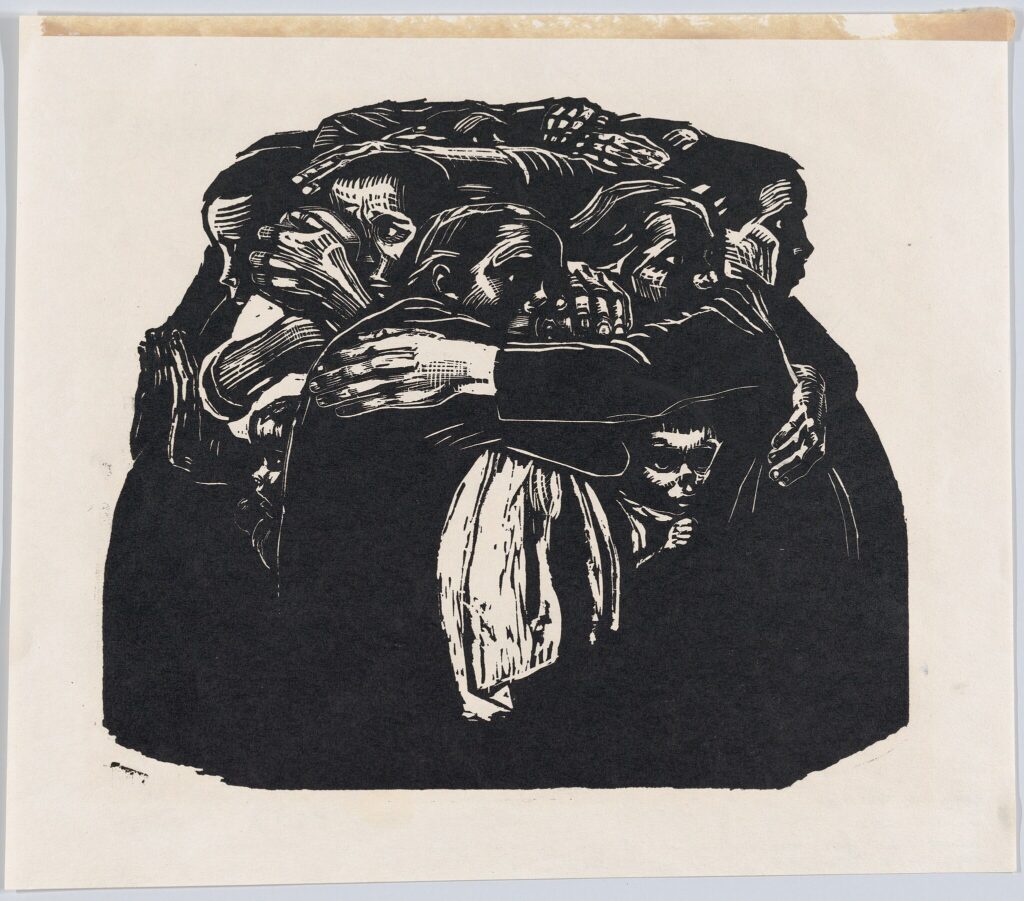

The Mothers (Die Mütter) by Käthe Kollwitz (1921-1922)

Käthe Kollwitz never directly fought in the war, but she lost her son Peter in its early months. That loss and her broader anti-war convictions shaped much of her work. The Mothers (Die Mütter) is part of a series of woodcuts titled War, where Kollwitz depicted the suffering of women, children, and civilians during conflict, again showing another side of the impacts of war beyond the Frontlines.

In this print, a group of women huddle together in mourning. Their faces depict anguish and sadness, highlighting the plights of those left behind. The strong composition of the woodcut medium heightens the emotional impact. Other woodcuts in the series depict widows, parents, and volunteers during the conflict. Discussing the series, Kollwitz wrote, “[It] is my confrontation with that part of my life, from 1914 to 1918, and these four years were difficult to reckon with.”

The War (Der Krieg) by Otto Dix (1929–1932)

A former machine-gunner in the German Army on the Eastern and Western Fronts, Otto Dix brought firsthand experience of the war’s violence to his art. The War (Der Krieg) is a polyptych painted over a decade later, similar in construction to religious triptychs of the Renaissance.

The central panel shows soldiers in gas masks trudging through an almost apocalyptic gassed landscape surrounded by remnants of war. To the left, a battalion readies for battle marching away, and to the right, a grey figure (a self-portrait of Dix) carries wounded soldiers toward the viewer. Below them, in the predella (the panel beneath the main section), dying or dead soldiers lie beneath the landscape, almost as if in a tomb. The pieces took three years to complete, with many details that depict all the horrors and complexities of war Dix experienced himself.

Articles you may also like

Remembering Long Tan: Australian army operations in South Vietnam 1966–1971

Reading time: 5 minutes

The anniversary of Long Tan reminds most Australians that despite winning that iconic high intensity battle, the Australians and New Zealanders lost the Vietnam War. In fact, the First Australian Task Force (1ATF) fought at least 16 big battles, and through superior firepower from artillery, armor and airpower, won them all, sometimes by a narrow margin.

But most of the struggle in Phuoc Tuy province and South Vietnam was a prolonged low intensity guerrilla war. The big battles only mattered if the US and her allies had lost them, as big battle success allowed the allies to stay in the War. Enemy defeats just forced the enemy to revert to low intensity guerrilla war, which the allies had to control if they were to win.

North Africa in WWII: Total War with Honour?

Reading time: 7 minutes

The North African campaigns during the Second World War have a reputation for being “clean” wars, free from the atrocities we see when studying the Eastern front or the Pacific theatre. However, when we look a little more closely, we can see this romanticized image is a little tarnished in places; we’ll take a look at what the historical record can tell us, as well as some details shared by Australian veterans of the conflict.

The Two Countries That ‘Escaped’ The Scramble for Africa

The Scramble for Africa is often recognized as the beginning of colonialism and European Imperialism. Beginning in 1884, the scramble brought most of the African continent under European control, barring two countries – Liberia and Ethiopia. However, debate continues over whether these regions truly escaped colonialism as they grapple with the same colonial legacies that […]

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.