Estimated reading time: 8 minutes

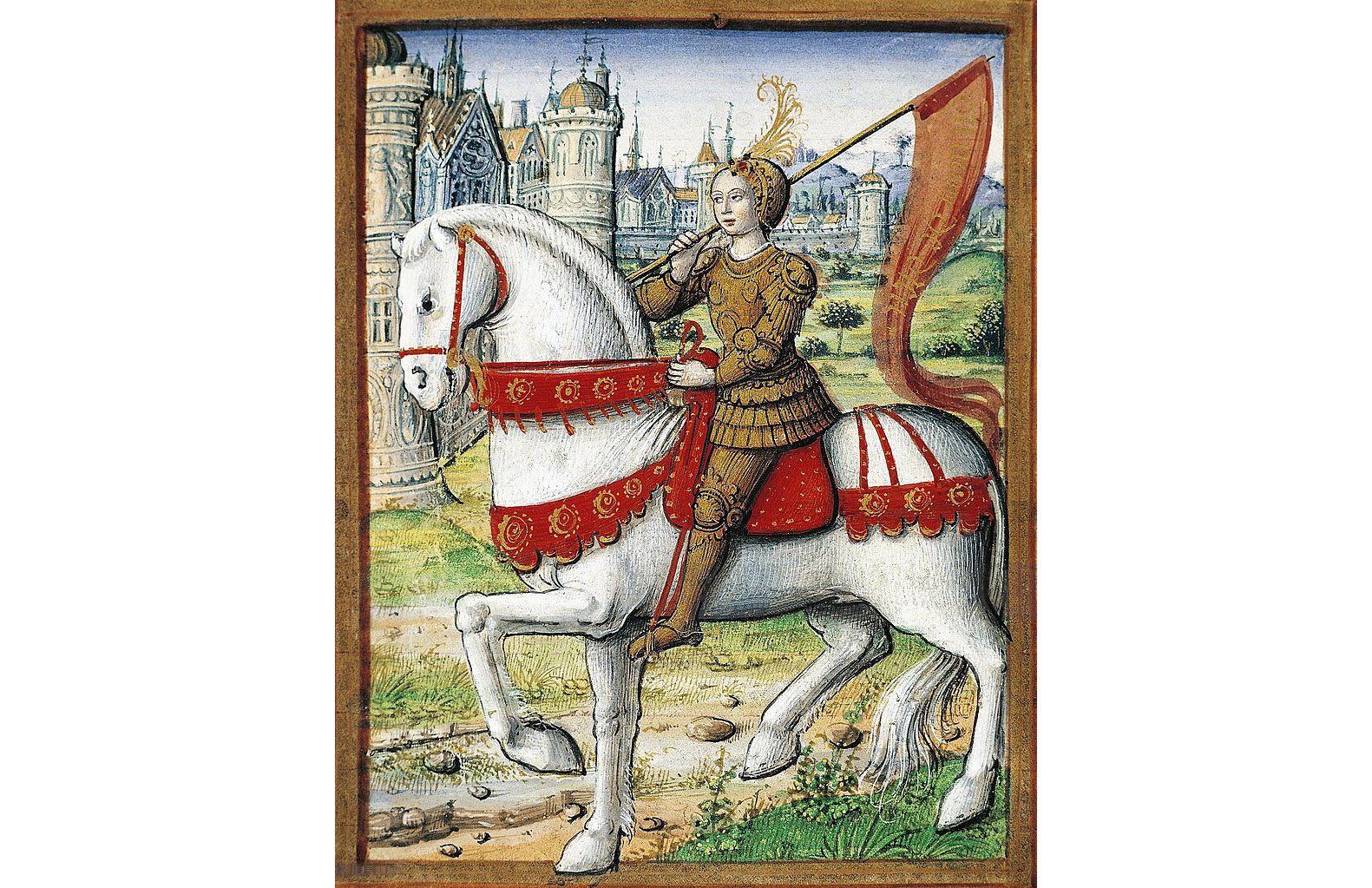

Last spring, I found myself in the surprising position of explaining to a student sitting in my office that Joan of Arc was real. At the small liberal arts college where I teach, Hollywood History is an intermediate course without prerequisites that fulfills a general education requirement. Unlike the upper-level medieval history elective, it fills reliably. For many students, the course is both their first contact with medieval history and the only engagement they will have with it in their college education. Teaching the course for the first time, I found that students struggled to discern the borders of fiction and reality in the medieval past. My students were easily able to picture a medieval past in which white men could do almost anything. They clung tenaciously to the belief in a real King Arthur who fought foreign invaders, and a real Robin Hood in Sherwood Forest. But they read Ibn Fadlan’s account of his diplomatic travels from Baghdad’s court to central Asia and northern Europe, and were still shocked to learn in class discussion, after watching The 13th Warrior (1999), that he really existed.

By Lucy Barnhouse.

Students struggle to assess the reliability of sources everywhere. A course exploring history as imagined on film invites students to see history as a subject for interpretation and themselves as competent critics of historical claims. By using media in which students are interested already, this course draws a more engaged audience than many introductory surveys. The course needs to introduce students effectively to the basics of medieval history, film studies, and medievalism (popular interpretations and representations of the medieval past). From a pessimist’s perspective, this might be something like a pedagogical nightmare. How, then, can I enable students to thrive in studying material that they find interesting but have not previously been given the tools to analyze? How can I teach students unfamiliar with historical content to engage intelligently with popular depictions of that history?

A decade ago, the work of medievalism was defined by Larry Scanlon as the attempt to bridge a chasm between a modernity imagined as axiomatic and a past assumed to be irrecoverably unknowable. In the vibrant literature on medievalism, comparatively little attention has been given to the undergraduate classroom. Thus, in writing and revising the class syllabus, I often found myself falling between the disciplines of history, literature, and film studies. The question of how to responsibly teach a past primarily familiar to students through seductive but misleading representations is, of course, not limited to medievalists. Moving forward, I’m revising assignment structure, changing the required texts, and categorically forbidding the use of the phrase “strong female character,” while doing more with other tropes. I’m also flipping almost all work on film analysis into the class itself, reducing the number of interpretative tasks that students are asked to perform on their own.

My first strategy for revising the course is adjusting the structure of assignments. The reading that generated the most discussion of the semester was the Charter of the Forest, as reissued in 1225 (available open-access through the UK National Archives). Paired with two of the earliest Robin Hood ballads, it proved more engaging than either of the other sources. Students asked good questions about economic and social relationships in 13th-century England, and about relationships between rulers and ruled. This productive experience, however, began with a misreading. The charter grants rights and resources to those who use the forest. Because this seemed to the students like the opposite of what medieval kings did, they read it as a centralization of royal power. In order to obviate such misreading, I have crafted short quizzes tailored to the primary sources, inviting students to do both close reading and comparison with the paired films. In the past, I have assigned responses to framing questions as reading accountability assignments, but the new assignment can be used as the basis for small group discussion and peer review in class.

A course exploring history as imagined on film invites students to see history as a subject for interpretation and themselves as competent critics of historical claims.

I’m also taking an alternate approach to providing background on the history portrayed in film. An English king giving privileges to his subjects, a Baghdadi diplomat traveling in the steppes and among Vikings, strange women lying in ponds distributing swords—all of these, I learned, carried roughly equal degrees of plausibility for my students. And, as I have discovered in teaching global history courses, this is not only true for the Middle Ages. For students entering college with minimal knowledge retained from high school history courses, blockbusters have shaped their visions of the past, from the gladiatorial arena to World War II battlefields and beyond. My original strategy for combating this in Hollywood History was to assign a brief introductory text on medieval history, a monograph on medievalism in film, and a collection of essays comparing portrayals of the Middle Ages in international cinemas. The latter was resented from the beginning; its density made it unreadable to my undergraduate students (or at least made them unwilling to read it).

Selecting short essays directly confronting misconceptions about history, or about particular clichés in media, allows students the fun of myth-busting, and demonstrates connections that are difficult for them to find independently. As for background on the historical period itself, while I initially feared duplicating content from history electives, offering robust contextualization in mini-lectures is, I think, a necessity—as well as a recruitment strategy for potential history majors. It also can be done through adapting material already prepared for other courses. For film theory, a few introductory essays may prove more effective than attempting to build student competence in a largely unfamiliar field. Particularly here, I’m relying increasingly on in-class work, including student workshopping of primary sources. Such small group work not only allows students to compare interpretations, but also shows them that they’re not alone in grappling with the challenges of unfamiliar history.

My third strategy for revamping the course involves framing. In the past, I gave students a set of framing questions to ask about Hollywood medievalism. Relying on students’ independent notetaking on films, however, proved to be a strategy with insufficient accountability. Using a mixture of questionnaires and trope bingo cards instead will, I hope, stimulate more discussion without sacrificing intellectual creativity. Playing “trope bingo” with banqueting scenes, oppressed peasants, and mysterious witches is surprisingly easy. It reinforces for students that tropes can be visual or plot-based, connected to characterization or script. It also introduces a competitive element that may be productive—at least in a course that, taught at night and promising knights in shining armor, attracts many student athletes.

Students typically used “strong female character” to mean “woman doing stereotypically masculine things,” not “complex character with meaningful agency.”

One trope I have chosen to excise from classroom discussion is the “strong female character.” This may seem like an odd, even draconian, choice, but I found that the term hampered discussions of characterization and reception. Students typically used it to mean “woman doing stereotypically masculine things,” not “complex character with meaningful agency.” They were far more ready, for instance, to read Keira Knightley’s leather-armor-wearing, longbow-shooting Guinevere (King Arthur, 2004) as a strong female character than Julia Ormond’s kingdom-administering, policy-making Guinevere (First Knight, 1995). Some of the term’s most productive discussions on gender centered on the figure of Olivia De Havilland’s Maid Marian (The Adventures of Robin Hood, 1938). Many students expressed strong views on her character in written responses. Some asserted that she was a mere damsel in distress; some that she subverted this trope; and some, yes, that she was a strong female character. I’m delighted to have such good justification for continuing to include one of my favorite films in the course.

Two framing elements remain unchanged from the original course. The first is the list of things to remember in the syllabus. This reminds students that questions are useful scholarly tools; that if something seems weird or confusing, it’s probably important; and that intellectual work can be, at its best, both rigorous and playful. The second is the opening quotation on the syllabus, from The Court Jester (1955): “Life couldn’t better be / on a medieval spree: / knights full of chivalry, / villains full of villainy!” By the time we get to The Court Jester at the end of the semester, students are prepared to appreciate the film’s Technicolor garishness, its trope spoofing, and its perfect casting of Basil Rathbone as the scheming minister and duelist. Ideally, they should also be ready to see history as a discipline of interpretation, rather than the march of facts they have been preconditioned to expect. Analyzing films and primary sources with both rigor and creativity offers students training in foundational historical skills. It not only helps students to distinguish fact from fiction but invites them to see history beyond Hollywood as containing more diverse possibilities, and more interesting truths, than previously imagined.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. It was originally published in Perspectives on History.