Reading time: 6 minutes

With its oldest known version penned around 400 BCE, the Hippocratic Oath has a long and illustrious past. However, despite its age, the document remains very much alive, and new perspectives surrounding its language and purpose are constantly emerging.

The Hippocratic Oath, like the other documents comprising the Hippocratic Corpus, is traditionally attributed to Hippocrates of Kos, who lived in Greece in the fifth century BCE. However, little is reliably known about Hippocrates himself, and some evidence suggests that the Oath, alongside other parts of the Hippocratic Corpus, were written after his death.

Known as the father of Western medicine, Hippocrates was the creator and figurehead of a new school of medical practice. The Hippocratic school emphasised professionalism in medicine, the free exchange of information between physicians, and a passive style of treatment. Hippocrates and his adherents also separated medicine from philosophy and religion—in the Hippocratic Corpus, no disease is said to have been caused by angry gods.

The earliest version of the Hippocratic Oath enshrines these principles. It commands that doctors act in the best interests of their patients, including keeping a patient’s medical information confidential and refraining from sex with patients. It also urges doctors to respect their teachers—and to pass on their own knowledge free of charge.

The original Hippocratic Oath also forbids euthanasia, abortion, and surgery. It specifically provides that the physician will not perform surgery even for the most painful of conditions, such as kidney stones. This particular provision stems from a time when surgery, being dangerous, was eschewed by physicians and left to barber-surgeons. (However, it is important to note that other portions of the Hippocratic Corpus provide instructions on how to carry out procedures like abortion and ‘cutting for the stone,’ suggesting that the Corpus was built up by multiple authors over time.)

The original Oath begins with a religious dedication: the Oath is sworn to Apollo, other gods who preside over medical matters, and “all the gods and goddesses.” Additionally, it ends with a commitment to follow the Oath’s principles, lest the oath-breaker suffer the loss of their good health and good name.

Perhaps ahead of their time, these principles—and the oath that outlined them—faded from the historical record for over a thousand years.

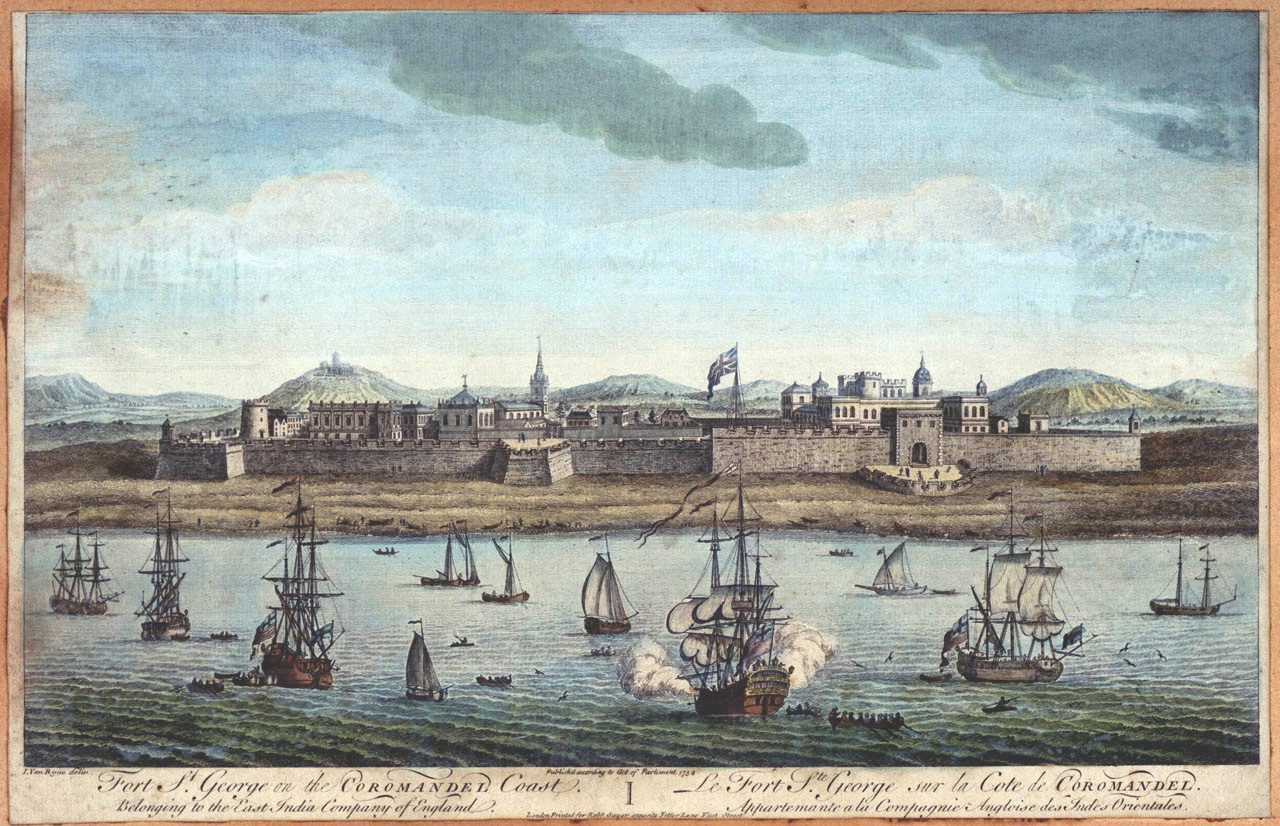

The thread picks up again in the year 1508, when a German-translated version of the Oath was sworn by new doctors at the University of Wittenberg. Still, widespread popularity in the Western world did not come until the eighteenth century, when the Oath was translated into English. After this point, new doctors in Europe and America began to swear a Christianised version of the Oath upon their graduation, sparking a tradition that would persist for centuries.

Eventually, in the wake of medical atrocities committed during World War II, some found the Hippocratic Oath of old to be insufficient. Still, it felt crucial that new doctors should swear to an inviolable code of ethics. For this purpose, the World Medical Association drafted the Declaration of Geneva in 1948. “It builds on the principles of the Hippocratic Oath,” says the WMA, “and is now known as its modern version.”

The Declaration of Geneva is a secular document, omitting references to any higher power. Unlike the original Hippocratic Oath, it does not forbid any specific medical procedure (such as abortion), but it does forbid the use of medical knowledge to violate any person’s human rights or civil liberties.

Still, the Hippocratic Oath continued to be widely used by medical schools during the twentieth century–despite changes in society and medical practice. Thus, Louis Lasagna, then-dean of the medical school at Tufts University, penned an updated version of the Oath in 1964.

Like the Declaration of Geneva, Lasagna’s Oath begins without any religious dedication, and emphasises the social responsibility of the physician. “I will remember that I remain a member of society, with special obligations to all my fellow human beings, those sound of mind and body as well as the infirm.”

Largely, however, Lasagna’s Oath follows the structure of the original. In the portion of the Oath where abortion, surgery, and euthanasia were once prohibited, Lasagna provides that human life must be treated with the utmost respect. However, Lasagna also prepares doctors for a time when “it may also be in [their] power to take a life.”

Notably, abortion is never mentioned in Lasagna’s version–in a document made for use by all medical school graduates, regardless of their beliefs, perhaps Lasagna thought it best to refrain from speaking in absolutes about a deeply controversial issue of the time.

Lasagna’s Oath ends as the original does, with an acknowledgement that following the principles laid out in the Oath will lead to success and happiness. Still, while the original threatens that doctors who break their oath will lose their good health and good name, Lasagna makes no such provision. His ending takes an entirely positive tone, with no warning of what may happen if medical ethics are deserted.

Over the course of the 20th century, the Hippocratic Oath gained popularity among medical schools. In 1928, 24% of medical schools had their graduates swear to the Hippocratic Oath, but that number had climbed to nearly 100% by the year 2000. Still, it was around the turn of the twenty-first century that the merits of the Hippocratic Oath became a bone of contention among medical scholars.

The Oath and its modernised versions have been criticised from a wide variety of standpoints. The original version is out of touch with modern medical practice, with its prohibition of procedures like surgery, and it requires the swearer to invoke the gods of Ancient Greece, which stands at odds with most modern people’s beliefs! The Hippocratic school’s approach to informed consent has also drawn scrutiny. In the words of Robert Veatch, “The old Hippocratic ethic saw the patient as a weak, debilitated, childlike victim, incapable of functioning as a real moral agent… The Hippocratic ethic is dead.”

Simultaneously, modern documents like Lasagna’s Hippocratic Oath and the Declaration of Geneva seem watered-down to some. Writing in a 2000 issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association, Dr. David Graham says that “many modern oaths have a bland, generalised air of ‘best wishes’ about them, being near-meaningless formalities devoid of any influence on how medicine is truly practiced.” And indeed, many modern versions of the Oath, including Lasagna’s version and the Declaration of Geneva, do not include provisions for what ought to happen to a doctor who breaks their solemn oath.

Such criticisms have led some in the medical field to call the document the “Hypocritic Oath.” Still, others continue to believe in the power of its original spirit: to remind doctors to use their exceptional knowledge, and their exalted position, with respect and humility.

Podcasts about the Hippocratic Oath

Articles you may also like

Why Gorbachev’s legacy still threatens Putin

Reading time: 5 minutes

Little remains of the legacy of Mikhail Gorbachev, the last Soviet leader and one of the greatest reformers in Russian history.

General History Quiz 98

1. Which of these regions did the English conquer and colonise first, Ireland, Australia, South Africa or India?

Try the full 10 question quiz.