Reading time: 6 minutes

December 7 marks the 50-year anniversary of the Blue Marble photograph. The crew of NASA’s Apollo 17 spacecraft – the last manned mission to the Moon – took a photograph of Earth and changed the way we visualised our planet forever.

Taken with a Hasselblad film camera, it was the first photograph taken of the whole round Earth and is believed to be the most reproduced image of all time. Up until this point, our view of ourselves had been disconnected and fragmented: there was no way to visualise the planet in its entirety.

Chari Larsson, Griffith University

The Apollo 17 crew were on their way to the moon when the photograph was captured at 29,000 kilometres (18,000 miles) from the Earth. It quickly became a symbol of harmony and unity.

The previous Apollo missions had taken photographs of the earth in part shadow. Earthrise shows a partial Earth, rising up from the moon’s surface.

In Blue Marble, the Earth appears in the centre of the frame, floating in space. It is possible to clearly see the African continent, as well as the Antarctica south polar ice cap.

Photographs like Blue Marble are quite hard to capture. To see the Earth as a full globe floating in space, lighting needs to be calculated carefully. The sun needs to be directly behind you. Astronaut Scott Kelly observes that this can be difficult to plan for when orbiting at high speeds.

Produced against a broader cultural and political context of the “space race” between the United States and the Soviet Union, the photograph revealed an unexpectedly neutral view of Earth with no borders.

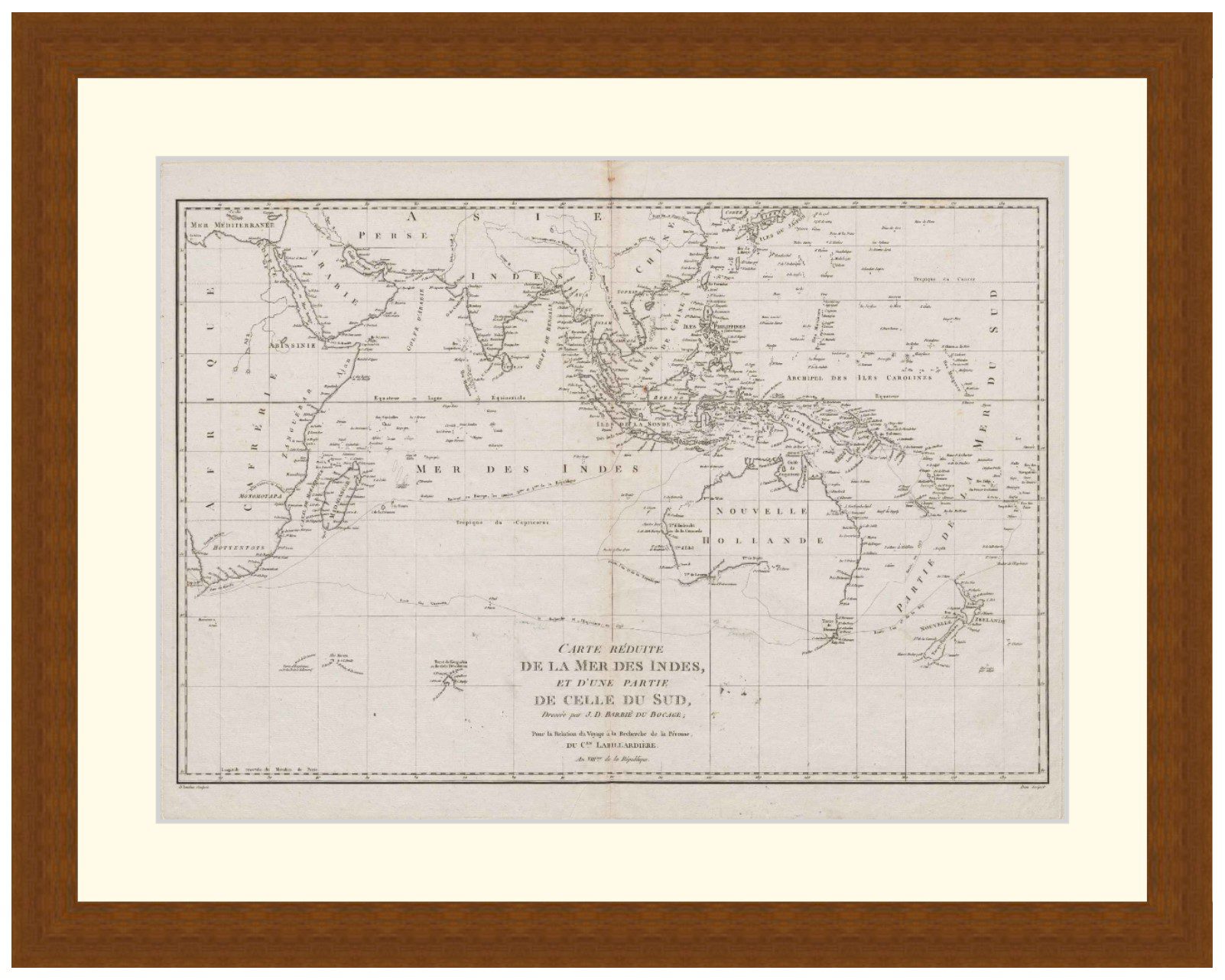

Disruption to mapping conventions

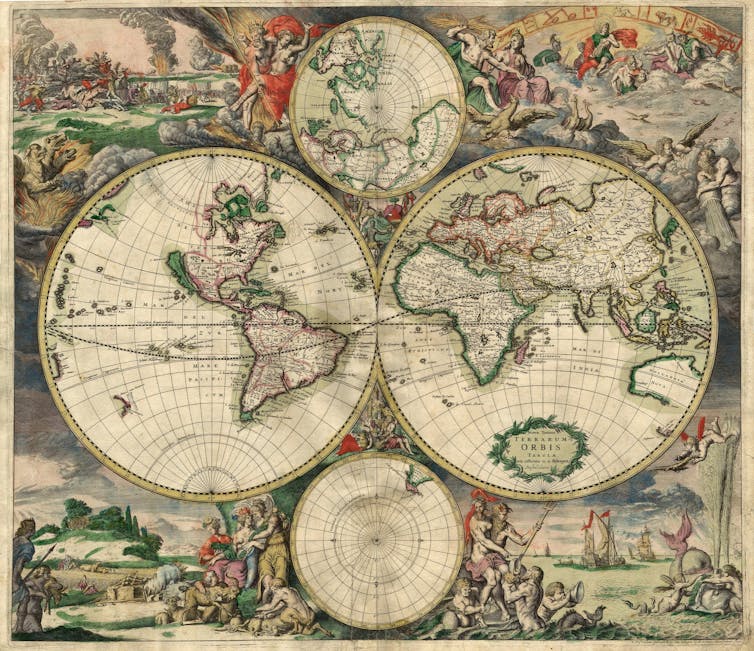

According to geographer Denis Cosgrove, the Blue Marble disrupted Western conventions for mapping and cartography. By removing the graticule – the grid of meridians and parallels humans place over the globe – the image represented an earth freed from mapping practices that had been in place for hundreds of years.

The photograph also gave Africa a central position in the representation of the world, where eurocentric mapping practice had tended to reduce Africa’s scale.

The image quickly became a symbol of harmony and unity. Instead of offering proof of America’s supremacy, the photograph fostered a sense of global interconnectedness.

Since the Enlightenment, mapping and map making had emphasised man’s superiority over the Earth. Working against this hierarchy, Blue Marble evoked a sense of humility. Earth appeared extremely fragile and in need of protection. In his book Earthrise, Robert Poole wrote:

Although no one found the words to say so at the time, the ‘Blue marble’ was a photographic manifesto for global justice.

Blue Marble’s afterlives

It is impossible to examine Blue Marble and separate it from the urgency of today’s climate crisis.

It quickly became a symbol of the early environmental movement, and was adopted by activist groups such as Friends of the Earth and annual events such as Earth Day.

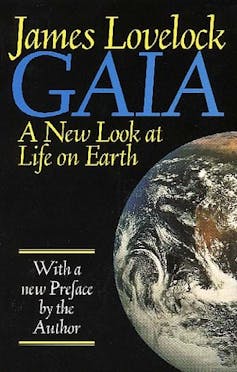

The photograph appeared on the cover of James Lovelock’s book Gaia (1979), postage stamps, and an early opening sequence of Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth (2006).

The ways we have viewed and visualised Earth have changed over the decades.

Commencing in the 1990s, NASA created digitally manipulated whole-Earth images titled Blue Marble: Next Generation, in honour of the original Apollo 17 mission.

These are composite images composed of data stitched together from thousands of images taken at different times by satellites.

Space-based imaging technology has continued to advance in its capacity to render astonishing detail. Art historians such as Elizabeth A. Kessler have linked these new generation of images picturing the cosmos with the philosophical concept of the sublime.

The photographs create a sense of vastness and awe that can leave the spectator overwhelmed, akin to 19th century Romantic paintings such as Thomas Moran’s The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone (1872).

In 1995, the Hubble Space Telescope revealed mountains of gas and dust in the Eagle Nebula. Known as the Pillars of Creation, the image captures gas and dust in the process of creating new stars.

Earlier this year, NASA released the first images taken by the James Webb Space Telescope.

Building on the Hubble’s discoveries, the Webb is designed to visualise infrared wavelengths at a unprecedented level of clarity.

These advances in technology might help explain the photograph’s enduring charm from the vantage point of 2022. The first photograph of our planet was remarkably lo-fi.

Blue Marble is the last full Earth photograph taken by an actual human using analogue film: developed in a darkroom when the crew returned to Earth.

Podcasts about the Blue Marble

Articles you may also like

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.