Reading time: 6 minutes

The slaughter of Australian soldiers at Gallipoli in 1915 is claimed by many to be a key factor in the building of our national identity. However, warfare on our own soil has been concealed beneath a code of secrecy and silence.

Peta Clancy’s Undercurrent exhibition at the Koorie Heritage Trust in Melbourne’s Federation Square aims to bring this hidden history to the surface, exploring the frontier wars and massacres that characterised Australia’s colonisation into the early 20th century.

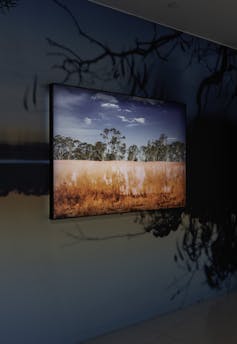

Comprising eight large, inkjet pigment prints and a 30-metre wallpaper installation, shot on 4 x 5 colour negative film, the exhibition seduces with familiar bush landscape views, then disrupts through slippages in time, space and context.

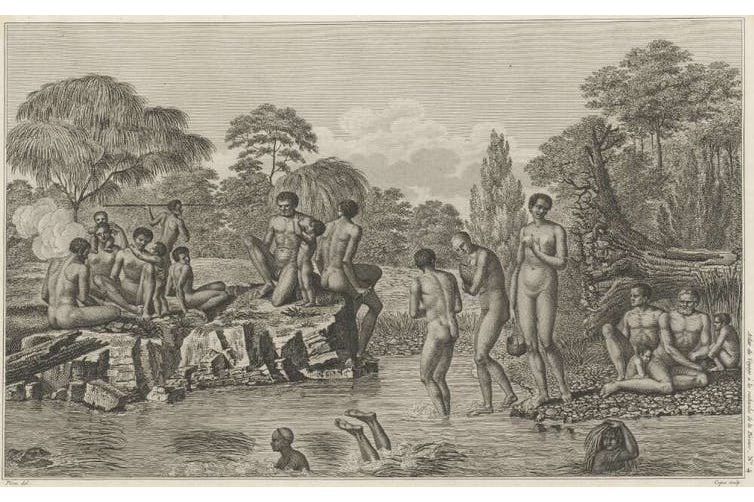

Massacres and massacre sites have a long history of being concealed, especially after the 1838 Myall Creek massacre, in which at least 28 unarmed Indigenous people were killed by colonists.

Seven white men were found guilty of murder and hanged following this massacre. The punishment was intended as a message that these atrocities would not be legally condoned. But rather than acting as a deterrent, this led only to greater concealment of massacres and massacre sites.

By Anita Pisch, Australian National University

In 1988, the year of the extravagant Australian Bicentennial celebrations, Bruce Elder’s Blood On the Wattle documented 26 frontier massacres Australia-wide. In the same year, the Koorie Heritage Trust compiled a Victorian Massacre Map showing the locations of known killings of Aborigines by Europeans between 1836 and 1853.

Far from comprehensive, the Massacre Map was published in 1991 and was an initial step in illuminating this hidden aspect of Australian colonial history. The publication of the digital map, Colonial Frontier Massacres in Central and Eastern Australia 1788-1930, by the University of Newcastle in 2017, further raised awareness of this issue in the national consciousness.

Australian artist and Monash University academic Peta Clancy first encountered the 1991 Massacre Map in 2016. She was researching her maternal lineage, connected to the Indigenous Bangerang people, traditional occupants of much of north-Eastern Victoria and areas of southern New South Wales, and photographing threatened butterflies and moths at Museum Victoria and the CSIRO in Canberra.

As her research progressed, her vision of the landscape was transformed by this undercurrent of hidden violence. Clancy sought a Cultural Heritage Permit to visit the massacre sites. In 2018, she undertook a 12-month residency at the Koorie Heritage Trust, collaborating with Dja Dja Wurrung Elders and community to create an artistic response to massacres on Dja Dja Wurrung Country.

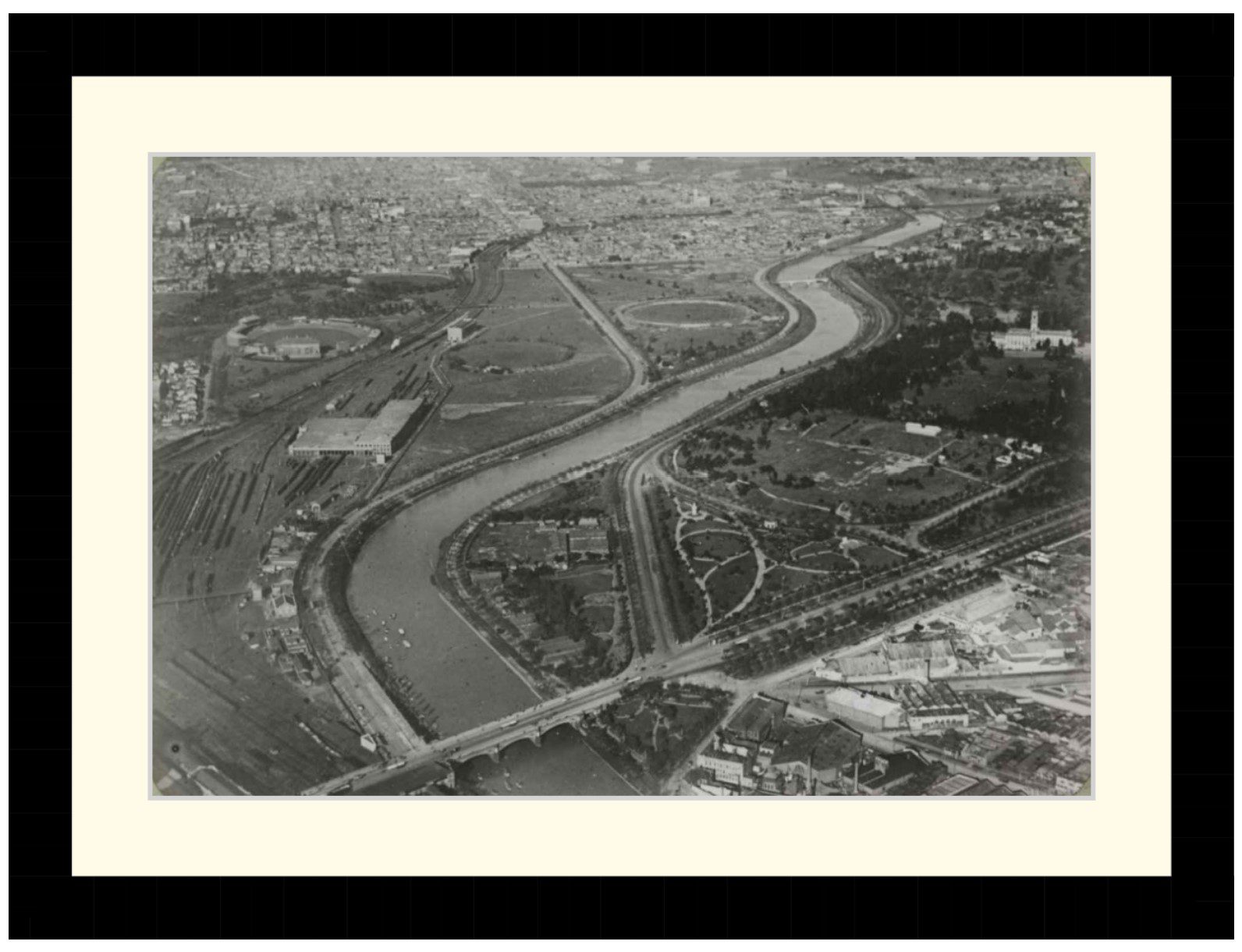

Clancy had initially planned to visit every massacre site on the 1991 map, however, over time, her focus narrowed to Dja Dja Wurrung Country in central Victoria. She visited sites with Traditional Owners, becoming particularly drawn to the metaphoric potentials of an 1870s massacre site known to the community. This site on the bank of the Loddon River had been flooded when a weir was constructed between 1889 and 1891, diverting the course of the river.

There is little detail on the massacre itself provided in the exhibition, perhaps out of respect to the community, but Clancy has developed her response to it through extensive collaboration with Dja Dja Wurrung people.

Victoria’s lush waterways and river beds, the sites of Aboriginal habitation where food and water were abundant, were also the most attractive spots for white settlement. The now underwater massacre site, near a popular tourist spot with caravan park, has a split existence as a place of ignorant bliss and concealed sorrow.

Clancy’s working methodology reveals the dual nature of the site. Beginning by taking conventional landscape shots there, she returned months later with these printed and attached to custom frames. Cutting into the original photos to reveal the landscape behind, she then re-photographed the scene through the frame, creating a genuine capture of the juxtaposed double images.

Comfortable viewing of the familiar landscape is disrupted by contrasts in focus, exposure and colour, with water sometimes appearing to threaten to engulf the treeline. Clancy highlights the existence of two worlds on the one site: earth and sky, past and present, mythic and historic, Indigenous and settler, oblivious joy and hidden violence.

Although looking at the same landscape, the happy holidaymakers and the Dja Dja Wurrung community experience wildly divergent perspectives – a dissociative response to past trauma which is too painful and thus hidden from consciousness. Reconciliation can only occur when both realities are brought to the surface and acknowledged as part of the history of the site.

Can a reviewer of European origin and other non-Indigenous observers make the attempt to alter our perspectives on the Australian landscape and admit another world view? Can we allow the possibility that shame over the massacres and denial of the truth continue to affect the present?

The land itself has been defiled. The ancestors denied an honourable death and those who carried murderous deeds to the grave haunt our collective present as well as our past.

Clancy sees the manual cutting of the photographic image as analogous to scarring. Although the images are rendered whole again, the scar line remains visible.

Despite signalling violence, Clancy views scarring in positive terms. “It is not the actual cut, which has healed,” she says, “but a reminder of the violence of the incision”.

Scarring is a sign of healing. Clancy reminds us of the trauma as a prerequisite for this healing to occur.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Articles you may also be interested in

When Australia Fought France, WW2 – Video

Operation Exporter was a little known, but very important campaign for the Australian military. It involved Australian’s fighting a strange war against confused Frenchmen who were not supposed to be our enemy. France had been defeated and subjugated by the Germans. The new French government, installed at Vichy, was answerable to the Führer. With France vanquished, the fate of their territories in Syria and Lebanon became uncertain.

William Cooper: the Indigenous leader who petitioned the king, demanding a Voice to Parliament in the 1930s

Reading time: 7 minutes

William Cooper is not a household name, but he should be. This Yorta Yorta elder is one of Australia’s most formative political leaders.

A Voyage Towards the South Pole and Round the World – Audiobook

On his first journey Cook mapped the east coast of Australia, on his second the British Admiralty sent him into the vast Southern Ocean. Equipped with one of the first accurate chronometers, Cook pushed his small vessel not merely into the Roaring Forties or the Furious Fifties but become the first explorer to penetrate the Antarctic Circle, reaching an incredible Latitude 71 degrees South, just failing to discover Antarctica.

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.