Reading time: 6 minutes

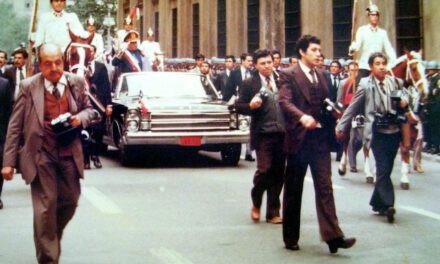

Gough Whitlam’s visit to China in 1971 is an iconic moment in the history of Australia-China relations. As prime minister, he officially recognised the People’s Republic of China the following year, heralding a new era of engagement with China.

But Whitlam’s visit overshadows an earlier and equally significant moment in Australia’s relationship with China.

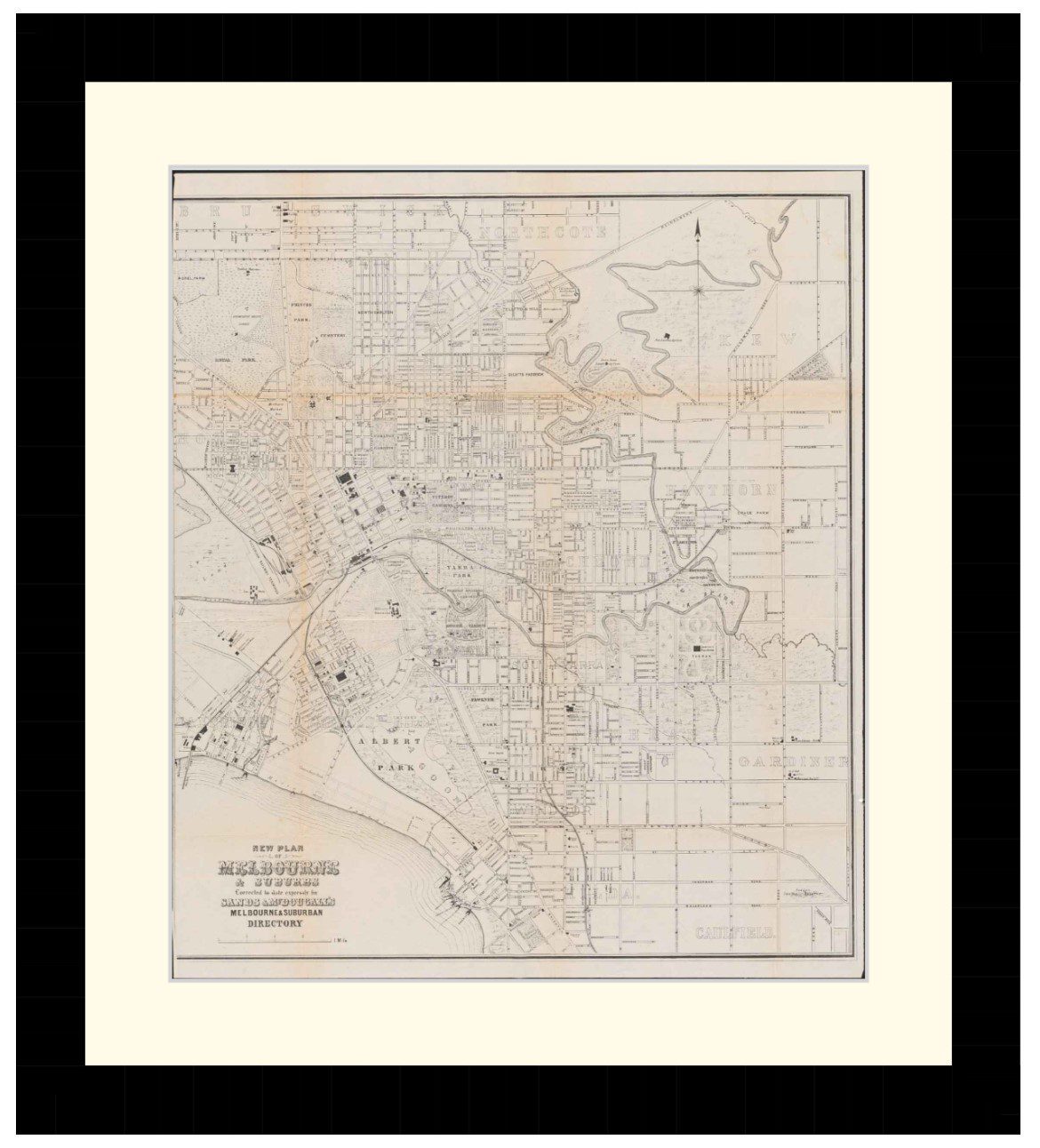

On October 28 1941, Australia opened its first diplomatic mission in China, a legation in the wartime capital of Chungking (Chongqing) in central Szechwan (Sichuan) province.

Until the 1930s, Australian foreign policy was still considered part of British Empire policy. But with the urgency of the second world war, Australia began to exercise a foreign policy distinct from Britain. Australia’s first overseas diplomatic missions were established in Washington and Tokyo in 1940. The Chungking Legation was the third.

By Kate Bagnall, University of Tasmania and Sophie Couchman, La Trobe University.

Australia announced its decision to appoint an Australian Minister to China in May 1941. Sir Frederic Eggleston was chosen for the role and his counterpart, the first Chinese Minister to Australia, Dr Hsu Mo (徐謨), arrived in Canberra in September 1941.

The notorious White Australia Policy was still in place, but by the end of the year Australia and China would be allies in defending the Pacific against the Japanese.

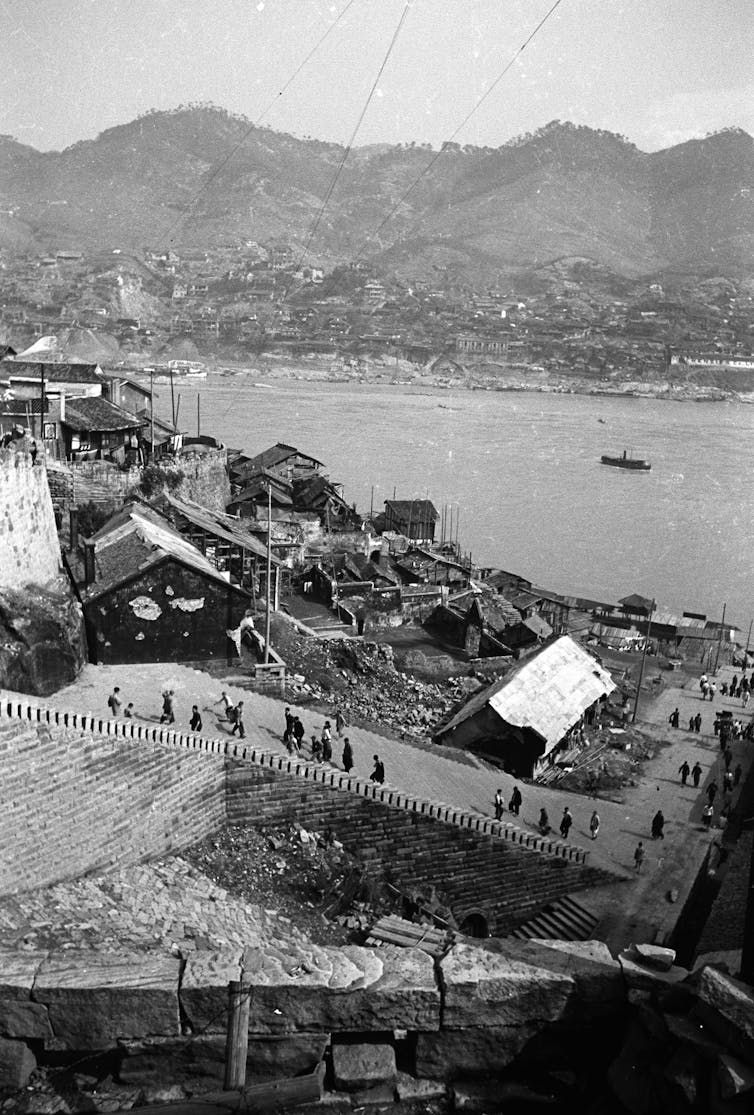

Wartime Chungking

China had been at war with Japan since July 1937. With much of the east coast of the country under Japanese occupation, Chungking served as the wartime capital.

Perched on the steep banks of the Yangtze River, the city was swollen with refugees, suffered heavy bombing, and faced shortages of food, housing and supplies.

An early challenge for the Legation was finding suitable premises and equipping it. Eventually, a building at No. 71 I Au Tze (遺愛祠) in the Li Family Estate (李家花園) became home to the offices and residence for the staff.

Legation staff were advised to bring all the clothes they would need, medicines including quinine (to treat malaria) and aspirin, and daily items like soap, toothpaste and boot polish. Other stores had to be ordered from India.

Transport to Chungking was difficult. People and supplies first came in by road over the Himalayas via the Burma Road. Later they came by plane, landing on a tiny island in the middle of the Yangtze River.

Alison Waller, wife of First Secretary Keith Waller, recalled, “you felt you had ten tin trunks sitting on your chest, and you couldn’t breathe because you had to fly right over the Himalayas”.

The Legation staff

Sir Frederic Eggleston (1875–1954), known as “The Egg” to staff, was a warm and thoughtful leader, and a popular and respected member of the foreign diplomatic community. A former lawyer and experienced public servant, Eggleston proved himself an able diplomat, serving in Chungking until 1944, when he was appointed Ambassador to the United States.

Diplomatic and office staff sent from Australia worked alongside locally employed staff, including a Chinese teacher, translators and clerks. Australian wives, such as Alison Waller, were also employed by the Legation.

Their work supported the Australian Minister to China, whose role, in Eggleston’s words, was “to interpret the Chinese viewpoint to Australia and the Australian viewpoint to China”.

Among the staff was the first Chinese-Australian diplomat, Charles Lee (1913–1996), who was born in the Northern Territory to Cantonese parents.

After graduating from the University of Queensland, Lee joined the public service in 1936. He was chosen to become Third Secretary in Chungking because of his general aptitude and his abilities with Cantonese and Japanese.

During his time in Chungking, Lee’s proficient language skills (now including Mandarin), local connections and general knowledge rendered him invaluable. He went on to represent Australia in Indonesia, Singapore and Spain, among other countries, and retired in 1973.

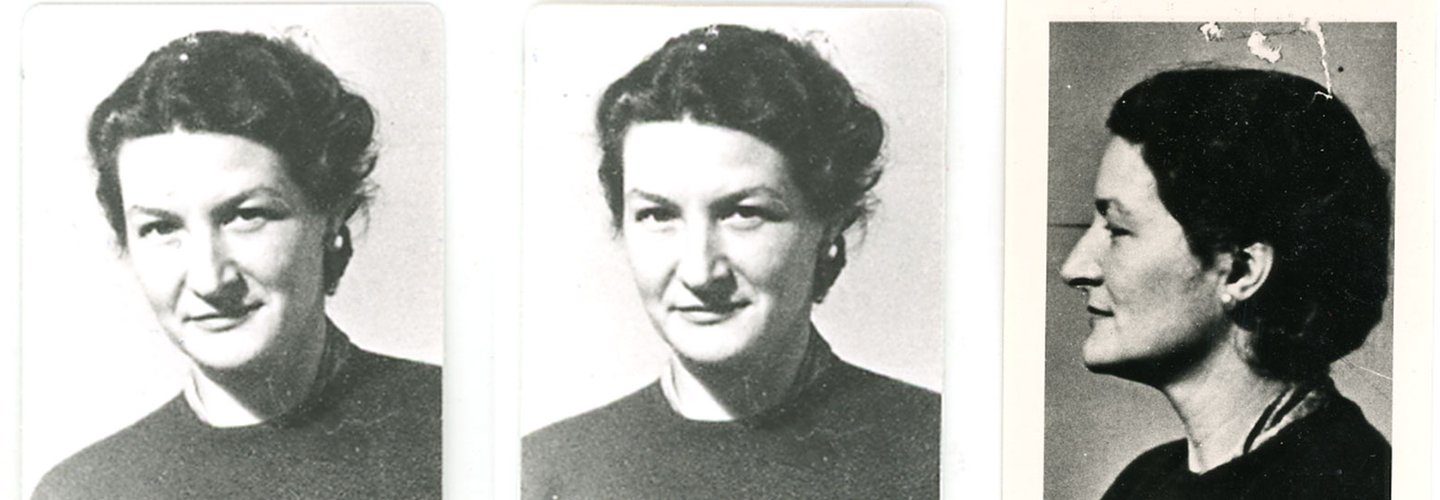

Another notable staffer was Maris King (1922–1997). Only 20 when she left Australia, alone, for Chungking in 1943, King worked as Eggleston’s secretary.

She stayed in Chungking for 15 months and later returned to work in Shanghai and Hong Kong. King went on to have a lifetime career as a diplomat, becoming only the second woman to head an Australian diplomatic mission before her retirement in 1984.

As she recalled of her time in China: “I had a ball! I’m surprised my mother let me go, looking back, because life overseas was so hazardous really in those days, with the war and all that, and I was very young – and female!”

After the war

Japan surrendered to China on September 9 1945. With the war over, the Nationalist government moved back to Nanking (Nanjing). The Australian Legation followed, relocating in April 1946 under the charge of a new Minister to China, Professor Douglas Berry Copland (1894–1971).

The Nanking Legation was upgraded to an embassy in 1948, and closed in 1949 after the Communists gained power. Charles Lee was the only member of the Chungking Legation to stay until the Nanking Embassy closed.

It would be another 24 years until, with Whitlam’s recognition of the People’s Republic of China, a new Australian Embassy opened in Beijing in 1973. But 80 years on, it is worth remembering the changing and complex relationship Australia has had with China.

This article was originally published in The Conversation

Articles you may also be interested in

Australia’s first known female voter, the famous Mrs Fanny Finch

Reading time: 7 minutes

On 22 January 1856, an extraordinary event in Australia’s history occurred. It is not part of our collective national identity, nor has it been mythologised over the decades through song, dance, or poetry. It doesn’t even have a hashtag. But on this day in the thriving gold rush town of Castlemaine, two women took to the polls and cast their votes in a democratic election.

Virginia Hall, SOE Agent to CIA Pioneer

Reading time: 10 minutes

Virginia Hall (1906–1982) was an American woman who served with the British Special Operations Executive in France in 1941–1942. She then joined its US equivalent, the Office of Strategic Services, and became a founding member of the Central Intelligence Agency.

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.