Reading time: 6 minutes

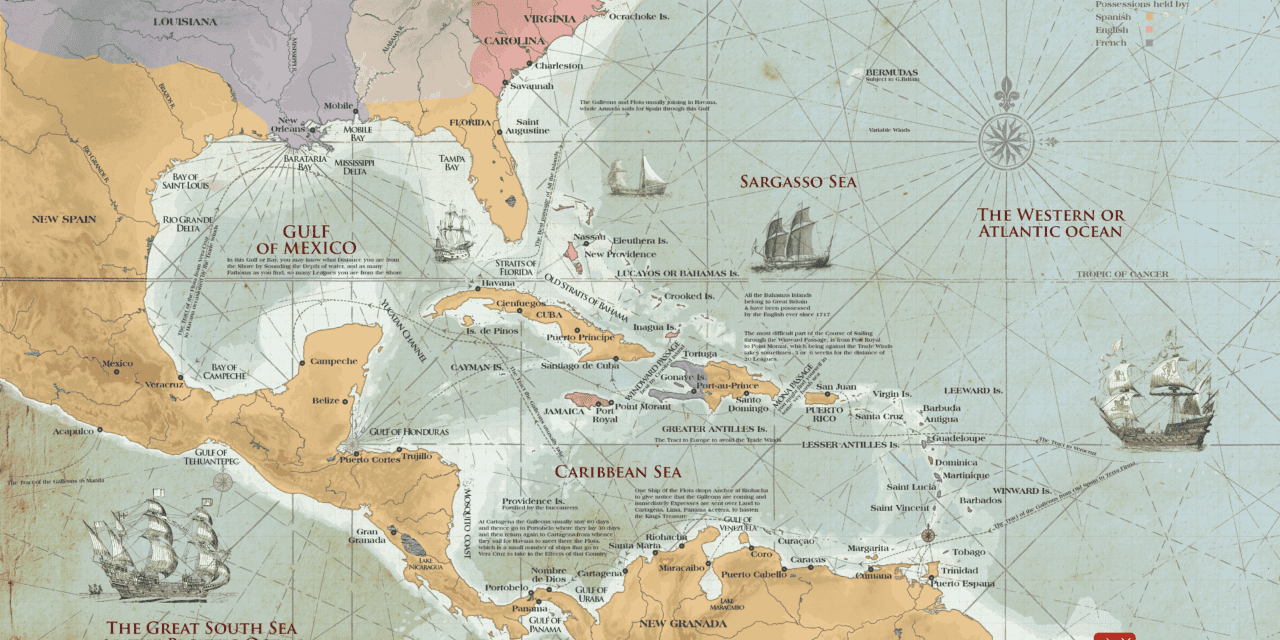

As the Age of Discovery slowly transitioned into the Age of Colonialism, the Spanish Empire, or more accurately its citizens, began importing African slaves into its new colonial holdings in North America and the Caribbean.

Only 30 years after Columbus had discovered the Americas, on the island of Hispaniola (now modern-day Haiti and the Dominican Republic), the very first colonial slave revolt occurred.

By Mark McKenzie

The Santo Domingo Slave Revolt of 1521 stands as a testament to the indomitable spirit of resistance among enslaved Africans, and would mark the beginning of a long and brutal struggle for freedom in the Caribbean.

Background of Slavery in Santo Domingo

Soon after the island’s discovery, the Spanish established a colony after suppressing native opposition, creating sugar plantations and new cities, with Santo Domingo being created in 1498, being the oldest permanent European settlement in the Americas.

Although the exact number of the native population of the Taíno is unknown, it is estimated that anywhere between a few hundred thousand to over a million inhabited the island before Columbus’ arrival. In less than ten years the last major army of the Taíno was defeated at the battle of Higüey in 1504, and by 1514, less than 25 years after discovery, only 32,000 Taíno remained, killed mostly from massacres, harsh enslavement conditions, or disease.

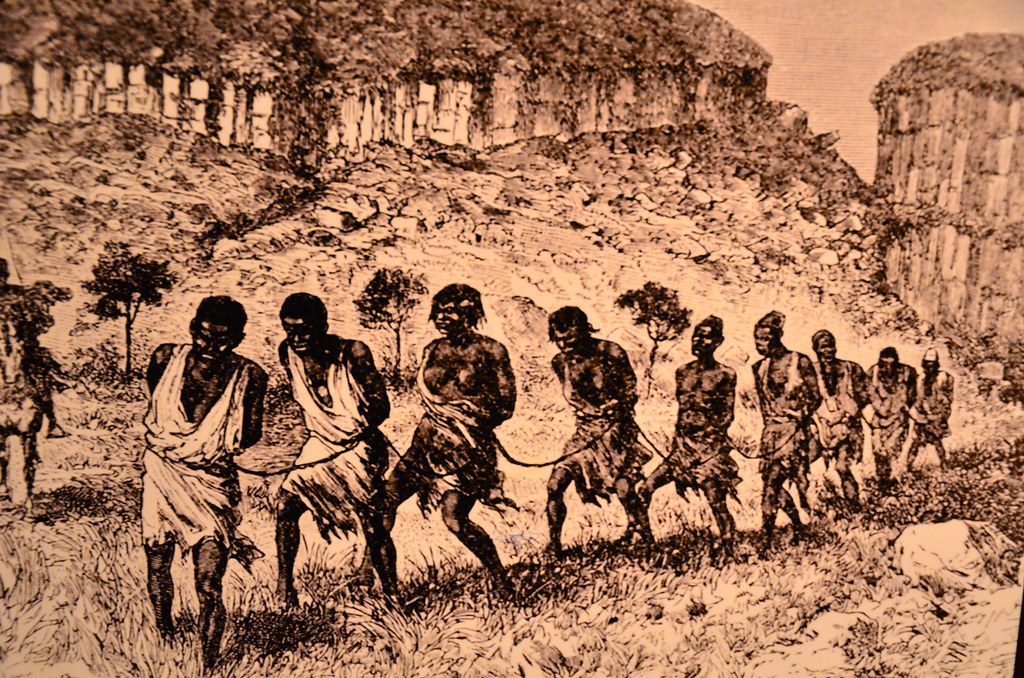

With the enslaved native population quickly diminishing due to harsh work conditions, the practice of shipping African slaves to the Americas as slave labour in the fields, mines, and households began in 1503.

Causes of the Slave Revolt

Just like the natives before them, the new enslaved Africans faced relentless exploitation and cruelty, working hard primarily in the island’s goldmines or sugar plantations.

There are few records on what specifically prompted the slave revolt aside from the general desire for freedom, however, it is important to remember that this was the early days of colonial slavery, and as such the Spanish overseers had not yet established many laws specifically designed to prevent uprisings.

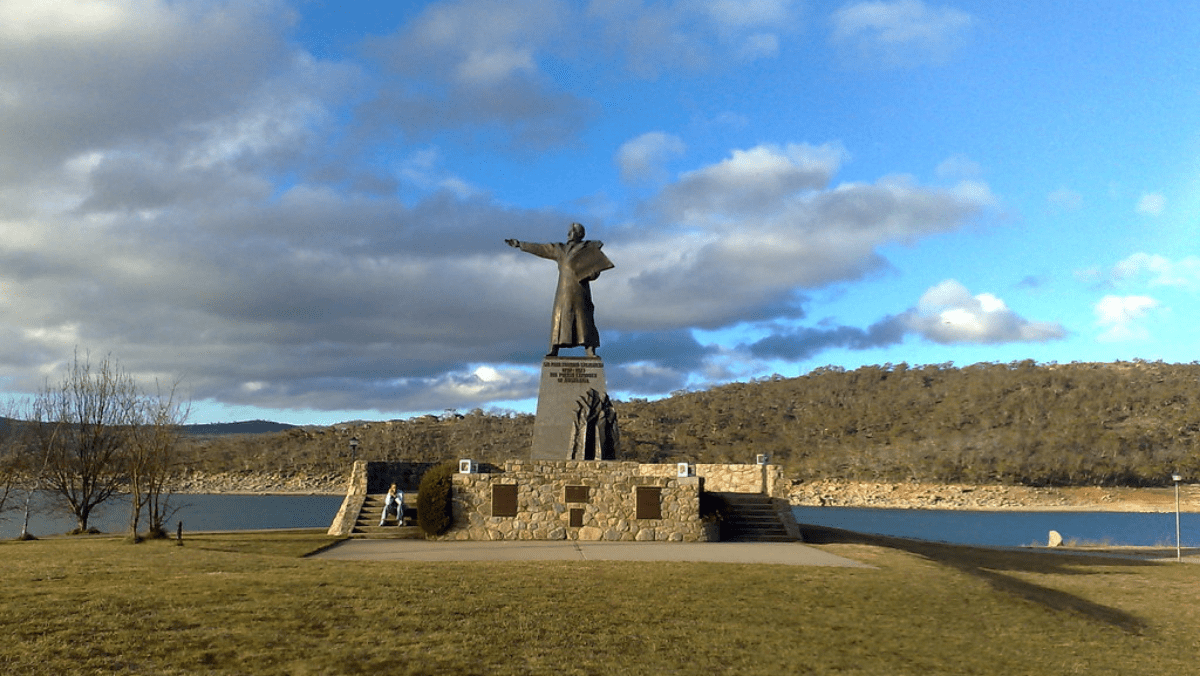

Not only this, but the enslaved Africans were witness to Enriquillo’s revolt, an uprising from the native inhabitants that lasted between 1519 and 1533 led by one of the last remaining native chiefs – Enriquillo.

Consistently raiding Spanish settlements, skirmishing with Spanish militia, and evading capture by hiding in the mountains, the actions of Enriquillo likely influenced and inspired the enslaved Africans, though there is no evidence of direct collusion between the insurrectionists and Enriquillo.

Organized, Efficient, and Almost Successful – What Actually Happened?

Though the exact date is contested, in 1521 around Christmas day, the tinderbox of resentment ignited, and the enslaved Africans of the island began their uprising.

According to local oral history, the rebellion began on the Nueva Isabela sugar plantation, the very plantation owned by the son of Christopher Columbus, and the island’s governor.

More than just being the first slave uprising in the Americas, the revolt was unique in its planning and organisation, with the rebels planning the revolt on Christmas specifically because they knew the white Spaniards would be deep in prayer.

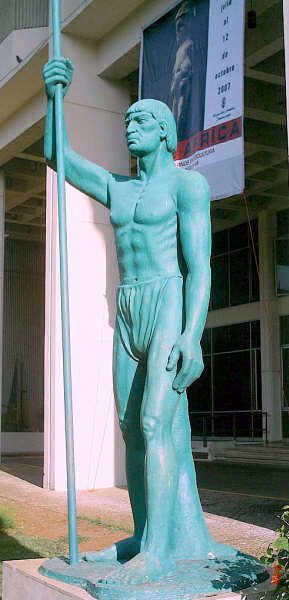

While we cannot be certain, local oral history states that the slave rebellion was led by Maria Olofa (Wolofa) and Gonzalo Mandinga, two African slaves from the same Wolof ethnic group in West Africa.

Although two of the leaders were from the same ethnic group, the revolt remains extremely impressive due to the fact that African slaves on the island had been captured from all over Africa, and thus spoke many different languages to each other.

Beginning at night along the Nigua River, the rebels marched 62 miles across the island from their plantations to villages, looting jewellery and weapons with the intent of massacring the white Spaniards and earning freedom.

Suppression of the Revolt

Upon discovering the uprising, Diego Colón (the governor) quickly organised a militia and sought out the rebels. The ensuing battle was swift and merciless.

Armed with much superior firepower of muskets and swords, while the rebels were armed with the few weapons they could find, but mostly those crafted from sharpened poles and farming equipment, the Spanish quickly ended the rebellion, executing the leaders and issuing harsh punishments for the other slaves.

Legacy and Impact of the 1521 Santo Domingo Slave Revolt

Preceding by hundreds of years the South American revolutions and the eventual abolition of slavery, the legacy of the Santo Domingo Slave Revolt endures as a beacon of resistance and resilience, with the very same island later becoming the Haitian colony made famous for its insurrections against colonial powers.

Realising how close the island had come to falling out of Spanish colonial hands, just ten days later in 1522 the Spanish introduced the first set of laws to limit the rights of black peoples, free or enslaved, inside the colonies, with the hopes of preventing further uprising.

Despite creating even harsher conditions for slaves, the 1521 Santo Domingo Slave Revolt is still celebrated 500 years later as a symbol of the fight for freedom and likely inspired many of the other slave revolts that would occur in the following several hundred years of colonialism and oppression.

Podcasts about the 1521 Santo Domingo Slave Revolt

Articles you may also like

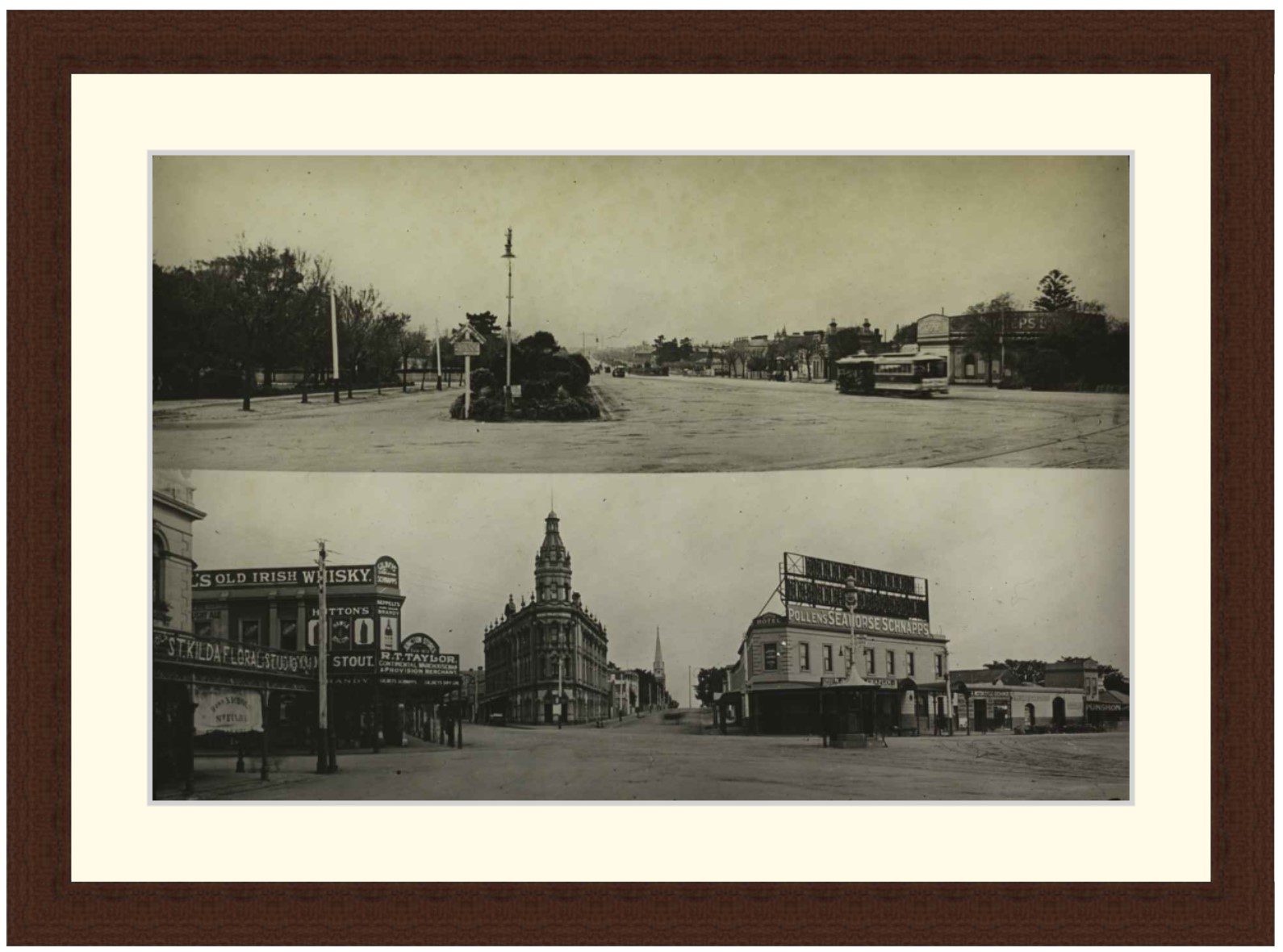

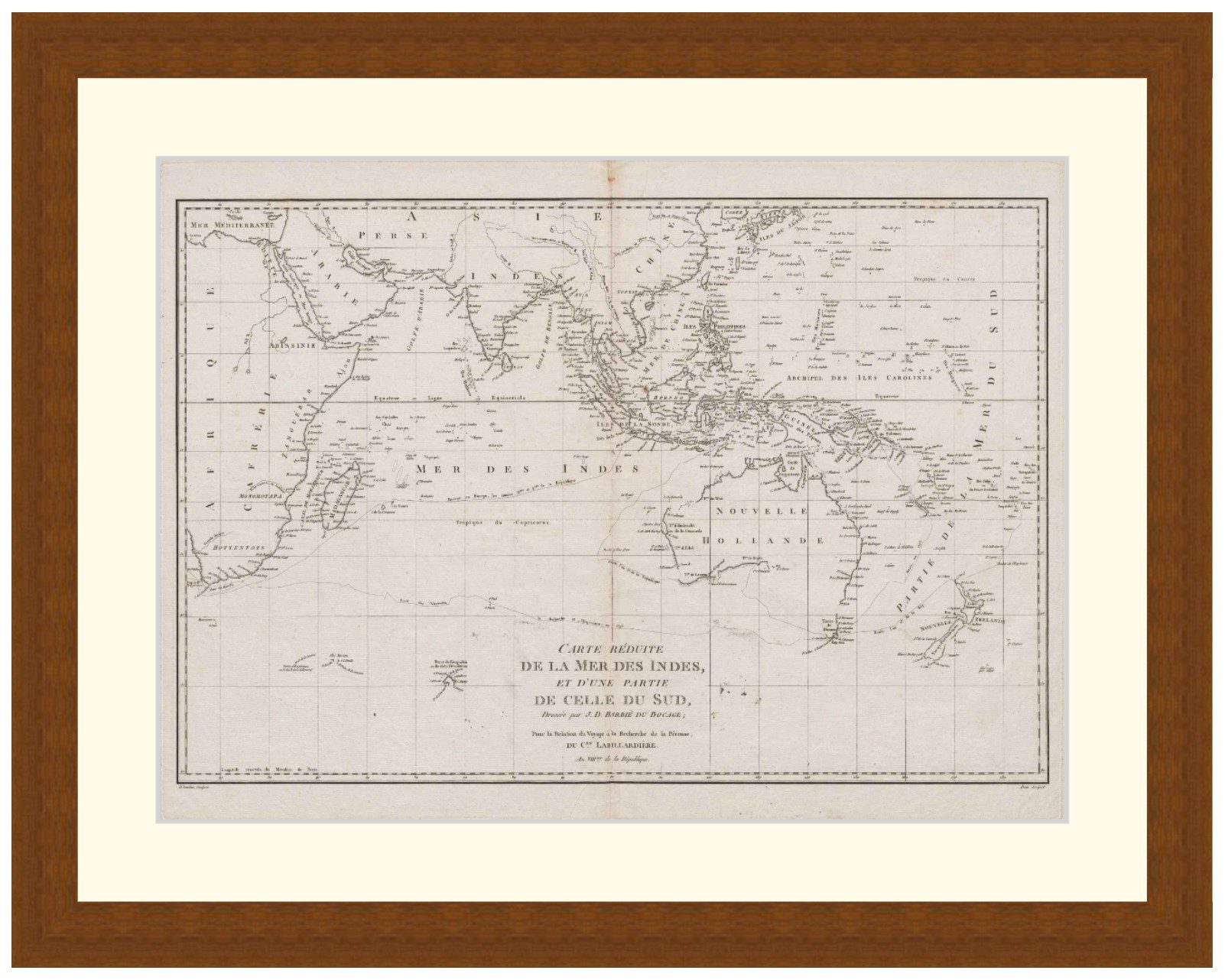

A tale of subterfuge, rivalry, Napoleon and snakes: how the NSW State Library came to own the map of Abel Tasman’s voyages

Reading time: 6 minutes

Every year, tens of thousands of New South Wales State Library patrons walk past a stunning mosaic replica of the Tasman Map on the floor of the Mitchell library vestibule. The original Tasman map, recently restored, charts the two voyages of the Dutch explorer Abel Tasman in 1642 and 1644.

Weekly History Quiz No.271

1. When was the first Sino-Indian War?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

The Political History of France, 1789-1910 – Audiobook

THE POLITICAL HISTORY OF FRANCE, 1789-1910 – AUDIOBOOK By Muriel O. Davis This little book opens on the eve of the French Revolution. The government is crippled by financial mismanagement, ruled by a King who, in the author’s words, is “devoid of both ability and energy,” and resented by a tax-oppressed peasantry and a rising […]

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.