Reading time: 11 minutes

This is the first of a planned series of blogs charting the progress of the Royal Navy Captains’ letters volunteer project. In it I make reference to letters which use terminology and refer to practices that may cause offence.

This project, scheduled for completion in 2024, involves cataloguing letters written by Royal Navy Captains to the Admiralty during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars (1793-1815). The National Archives holds these letters in 564 boxes in the record series ADM 1, archived by year and the initial letter of Captains’ surnames.

By Bruno Pappalardo, The National Archives

The Volunteer team is busily sorting, foliating and summarising the contents of this material, to make it keyword searchable on The National Archives’ catalogue, Discovery, for example by a ship, captain or place name, so that researchers can see details of all letters relevant to their search terms. This work is now complete for Captains whose surnames begin with the letter ‘A’, in the document references ADM 1/1448-1456, amounting to 2,200 letters and 756 enclosures.

On closer scrutiny of these letters it is clear they are not just letters written by Captains serving on board Royal Navy ships. Interestingly, there is a surprising mix of letters, ranging from Captains serving as Regulating Officers in command of press gangs, who recruited men, sometimes forcibly, into the Royal Navy, and letters by Lieutenants placed in command of Royal Navy ships, who in this context were deemed Captains. Moreover, there are letters from Naval Agents acting on behalf of Captains, often concerning pay and appointments.

There are also letters from Captains in command of Sea Fencible districts. (The Sea Fencibles, formed in 1793, were the Royal Naval equivalent of the Army Militia. It was composed mostly of volunteers, many of whom were fishermen or the inhabitants of coastal counties. They acted as a defence force against invasion during 1793-1815).

Furthermore, there are letters (enclosures) being forwarded by Captains to the Admiralty, for information purposes, for instance, from Admirals, fellow Captains, foreign dignitaries and other senior military officials. Lastly, there are also letters not necessarily authored by the Captains themselves but which might well refer to them in the body of the text of letters sent by other individuals.

It is really an eye opener to see the wide range of matters Royal Navy Captains dealt with in the age of sail. These topics range from the discipline, morale and health of the men serving on board their ships (including Royal Marines), expenses, supplies of food and drink, intelligence, the state and condition of their ships, appointments, promotions, capturing of enemy ships, accounts of battles and foreign diplomatic matters, just to name a few!

In these letters the character, actions, trials and tribulations of Royal Navy Captains during 1793-1815 are intimately revealed and through the work of a dedicated Volunteers team are being brought to light for all to see.

With so many letters it is difficult to pinpoint all the highlights contained in ADM 1/1448-1456. However, here are some of the most immediate finds which provide a flavour of what can be found.

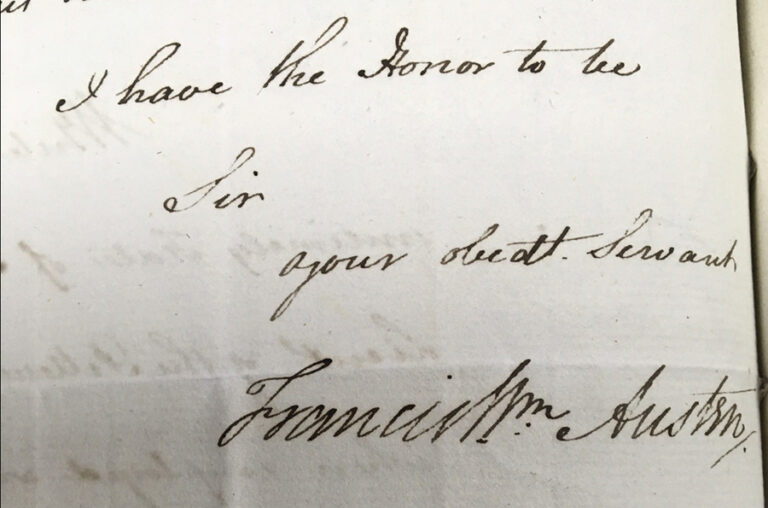

There are 72 letters by Charles John Austen and 150 letters by Francis William Austen, who both became high-ranking Admirals in the Royal Navy, but perhaps better known as the brothers of the renowned novelist Jane Austen. She may well have drawn on her brothers’ first-hand experiences to inform her literary output, with characters such as Captain Frederick Wentworth in her posthumously published novel, Persuasion (1817). Indeed, Francis offers a glimpse of his own quality of penmanship in a letter to the Admiralty (ADM 1/1449/124) he wrote from HMS Peterel, Port Mahon on 2 December 1799, reporting the demise of his First Lieutenant, James Wallace Brenton, who died of a wound received in action when cutting out a merchant vessel near Barcelona. ‘I feel it a justice due to his memory, … that during the whole time of my commanding the Peterel, I had every reason to approve of his conduct as an officer, and on several occasions had opportunities of remarking that he was possessed of great intrepidity, cool judgement, and active zeal for the service, and had it pleased heaven to have prolonged his life, I am firmly convinced he would have proved an ornament to his profession. Hoping that the rewards due to his uncommon merit, which cannot be conferred on himself may by their Lordships be admitted as claims to their patronage on behalf of his brothers’.

A characteristic of these Captains’ letters are the many examples of suggested improvements to Royal Navy service. One of the most deadly diseases encountered by the Royal Navy was yellow fever (a disease, not known at the time, to be spread by infected mosquitoes, particularly in tropical climates). Captain James Anderson, in a detailed proposal dated 7 June 1806 (ADM 1/1449/124), submits for consideration a scheme to prevent yellow fever and reducing the high mortality rate of crews serving on ships in the West Indies, stating his 12 years’ service in the area has allowed him to understand the cause and concludes it originates with the watering parties and launches’ crews. He suggests the adoption of seven regulations, the first being that only black and coloured men are employed on all watering parties and other services as they are capable of performing where much exposure to the sun is requisite, and secondly that a ship’s crew is not exposed to the sun between 11:00 and 14:00. His other regulations detail the need to air, clean and fumigate a ship as well as the need for cleanliness to be maintained by a ship’s crew. He states that in the eight years he has commanded armed vessels in the Islands, he has never lost a single man to yellow fever, even though he frequently transported troops.

Another enclosure dated 25 April 1811 (ADM 1/1453/149) offers perhaps an unusual remedy to treat a violent scorbutic complaint (a symptom of scurvy, a disease caused by the lack of vitamin C in a seaman’s diet described as the scourge of the Royal Navy). Captain Arden Adderley’s surgeon explains that Adderley cannot join his ship as ordered as he is suffering a violent scorbutic complaint and recommends that Adderley takes the waters in Lymington near Warwick, England, for up to 10 days to recuperate his health.

Aside from disease, drunkenness was an acute problem for the Royal Navy leading to many accidents, acts of disobedience and deaths. In a letter dated 17 October 1806 (ADM 1/1451/86), George Andrews, Regulating Officer at Dublin, describes the deaths of six newly recruited seamen and Royal Marines from excessive drinking of spirits. He states that it appears his Officers, contrary to his strict orders, have allowed liquor to be taken on board in such quantities to cause these deaths and fears ‘no amount of vigilance will prevent this occurring’ as long as men receive their bounties (financial inducement for enlisting) before joining their ship.

The Captains’ correspondence also include extremely rare examples of letters written by lower deck sailors (ratings), for example a letter (ADM 1/1451/155) dated 16 December 1806 by Michael Usher, seaman on HMS Royal Sovereign to his sister, Mrs Byrne, living in 58 Thomas Street, Dublin, Ireland. He informs her that he will be sailing in about three weeks on HMS Royal Sovereign in a convoy from Cork to the West Indies. He asks her to let Mary (his wife) know that he has not yet been paid but he will send £7 or £8 as soon as he can. He adds that his wife must obtain a certificate otherwise she will not be able to receive the money. Usher then implores his wife not to be angry with him for not sending for her but it would be foolish for her to visit him in such a place as a Man of War. Revealingly Usher states that there are two women from Dublin on board but they had been on board before in the last war. Finally, he promises to send books to them as a remembrance of him when he is dead and declares he is glad to leave the land and go to sea as he is tired of his life in the Channel and as there might be a chance of some prize money at sea.

There is also a heart-rending story of Benjamin Major, who was drafted on board HMS Ceres on 23 May 1811 as a boy aged just 13. In a letter (ADM 1/1453/100), he writes from HMS Erebus in Yarmouth on 3 January 1811 to his mother at 14 Hart Street, Grosvenor Square, London, stating ‘Dear Parents, I take this opportunity of writing these few lines, hoping to find you in good health … We arrived here this morning, and I am very sorry I could not get any opportunity of sending you a letter before: but we have been at sea this long time, and in great distress, as that we have had no possible means of sending anything away; so I hope you will forgive me. We expect to sail very shortly for Sheerness, and as soon as we arrive there I will let you know. My thoughts are entirely upon you; I am quite tired of a seafaring life, and I wish to rejoin my friends once more. If I ever get clear of this, I shall know how to value a good home and friends but since I have brought it upon myself, I can blame no one but myself for it; I see plainly I have acted very wrong, and I am very sorry for what I have done: but what is done cannot be undone. I morn to be released from this and to be inclosed again in, the arms of an affectionate parent.’

The Captains’ letters also reveal the types of men that served in the Royal Navy albeit as a result of different circumstances, indicating its cosmopolitan make up, while also sometimes providing physical descriptions of them and making passing references to women on board ships.

In a letter dated 19 February 1799 by Captain James Alms of HMS Repulse at Portsmouth harbour (ADM 1/1449/99) sent on request to the Admiralty, Alms states that ‘John Powers, Able Seaman, is thirty years of age, a black, married in Philadelphia and has his wife on board, is a native of New York entered on board His Majesty’s ship under my command on 4th October 1797 in a draft from La Raison, says he was pressed on the coast of America by Captain Berrisford and has received the bounty. He has a letter… from Mr Lenox, American Agent in London, to acquaint him his certificate was sent to their Lordships’.

A letter dated 22 June 1811 (ADM 1/1453/174), from HMS Colossus off Brest by Lieutenant John Lindsay to Captain Thomas Alexander, HMS Colossus reveals a strong dedication to duty: ‘Sir, having been absent from my native place Kirkwall, Orkney (Scotland), more than 21 years, 16 of which I have served without (a break) in His Majesties service and circumstances having occurred in my family very lately which render my presence necessary. I have to beg you will please to make the necessary application to … the Admiralty for my being superceded that I may lose no time in getting to so distant a part of the country for the benefit of my private affairs.’

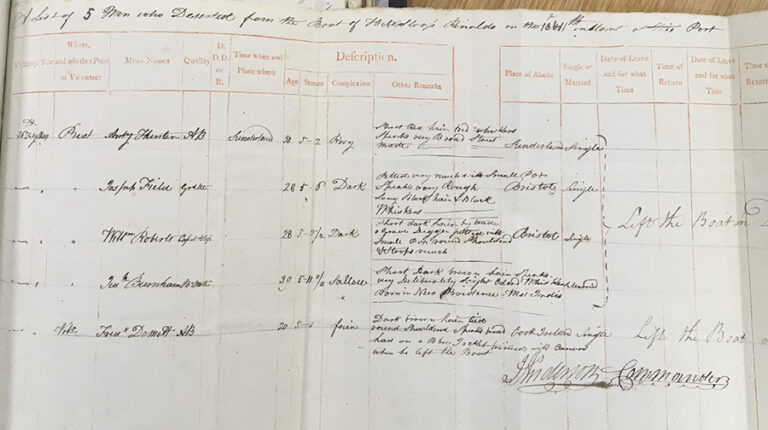

A return (ADM 1/1452/214) of the desertion of five men from the boat of HMS Rinaldo in the Downs on 10 and 11 November 1809 vividly describes one of the men: ‘William Roberts from Bristol, captain of the main top, aged 28, 5ft 3 ½ inches, dark, short dark hair, by trade a grave digger, pitted with small pox, round shouldered and stoops much.’

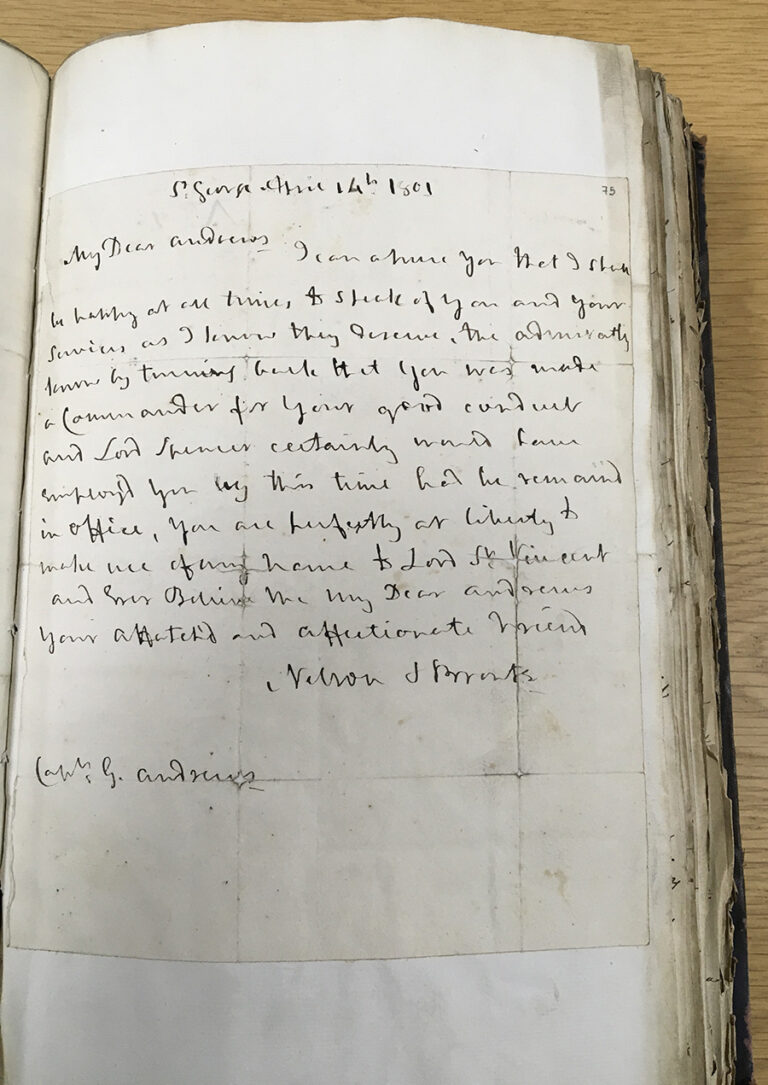

Patronage, influence and powerful contacts were extremely important factors in the progress of a Captain’s career. There are many examples of these forces at play among these Captains’ letters. Captain George Andrews with a petition to the Admiralty dated 9 April 1796 outlining his service from 1770 (ADM 1/1452/43) encloses a handwritten letter written by Lord Admiral Horatio Nelson in which he states in reference to Andrews ‘that he would be happy at all times to speak of you and your services as I know they deserve’ and that Andrews is ‘perfectly at liberty to make use of my name to Lord St Vincent and ever believe me my Dear Andrews your attached and affectionate friend’.

I would like to take this opportunity to thank all the volunteers involved in this project and for their ongoing contributions.

This article was originally published in The National Archives.

Podcasts about life in the Royal Navy during the Age of Sail

Articles you may also like

Weekly History Quiz No.271

1. When was the first Sino-Indian War?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

The R1 – South African Bush Rifle

Reading time: 9 minutes

In the wake of the rise of the Soviet Union’s AK-47 and the USA’s litany of rifles during the Cold War, South Africa needed a modern automatic service rifle. After trialling several different guns, the South African government settled on the Belgian FN FAL battle rifle. As a result, the “Rifle R1” was born – the bush gun of Southern Africa.

This article was first published by The National Archives. It is reproduced in accordance with the Open Government Licence v3.0.