Reading time: 6 minutes

Christmas has become a cultural event, associated with the giving of gifts and lavish meals with friends and family.

But the traditional understanding of Christmas is that it’s a Christian celebration of the birth of Jesus.

The idea of giving gifts may be traced to the Bible, in which the infant Jesus was presented with gold, frankincense and myrrh by the Three Wise Men, named in apocryphal texts as Caspar, Balthasar and Melchior.

This received a boost in the Middle Ages, when Boxing Day, December 26, became a holiday when masters gave their apprentices and other employees “boxes” – that is, gifts.

Yet the celebration of Christmas has distinct variations around the world. Some of these local traditions are very interesting and arise from particular historical circumstances.

The figure of Santa Claus, the jolly bringer of presents to good children, is derived from St Nicholas, a fourth-century Christian bishop of Myra.

Two famous stories are told of him, that associate him with gifts and children:

- He rescued three girls from a life of prostitution by giving their father three bags of gold for their dowries.

- He brought back to life three young boys who had been murdered and pickled by an evil innkeeper.

Santa Claus has elves and reindeer as companions in general Western folklore. But in other traditions around the world, Santa’s helpers are far less friendly.

The Netherlands: naughty kids are taken to Spain

In the Netherlands, Sinterklaaas brings children presents on December 5 (the day before the feast of St Nicholas, December 6).

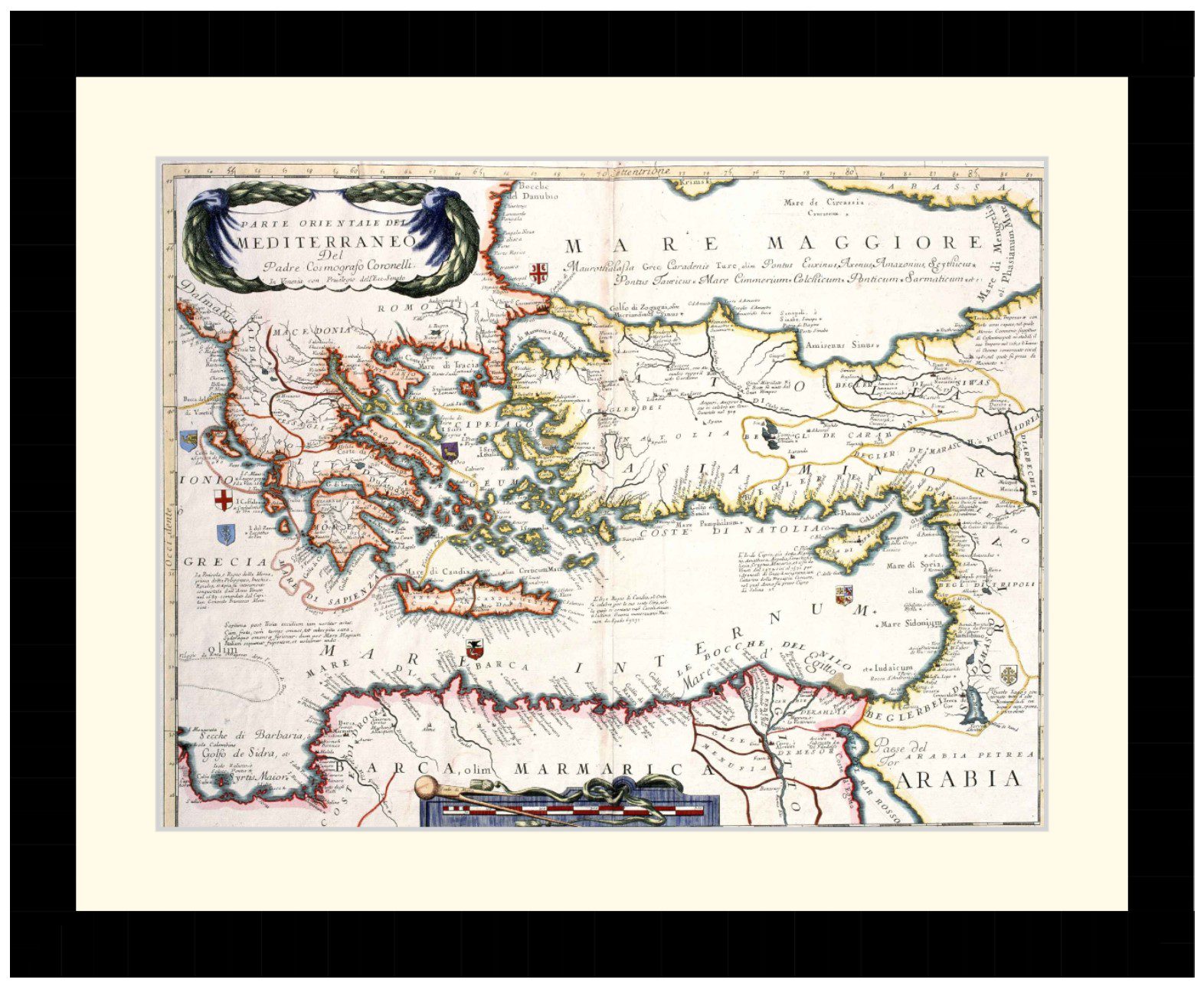

Dutch traditions say that Sinterklaas lives in Madrid, wears a red clerical robe and a bishop’s mitre, and has servants called “Zwarte Pieten” (Black Peters).

He arrives each year at a different port on November 11. Children prepare by leaving carrots for his horse and putting out a shoe for presents to be put in.

The Zwarte Pieten keep lists of the naughty children who receive pieces of coal rather than gifts. Very naughty children are put into sacks and taken to Spain as a punishment.

The reason Sinterklaas lives in Madrid is because between 1518 and 1714 the Netherlands was under the control of the Holy Roman Empire, at that time ruled by the Hapsburg Dynasty of Spain. Spain, therefore, meted out both punishments and rewards to the Netherlands (as the Zwarte Pieten and Sinterklaas do to Dutch children).

Though Zwarte Pieten are black because they spent so much time in chimneys, in the modern Netherlands many are concerned that they may be racist.

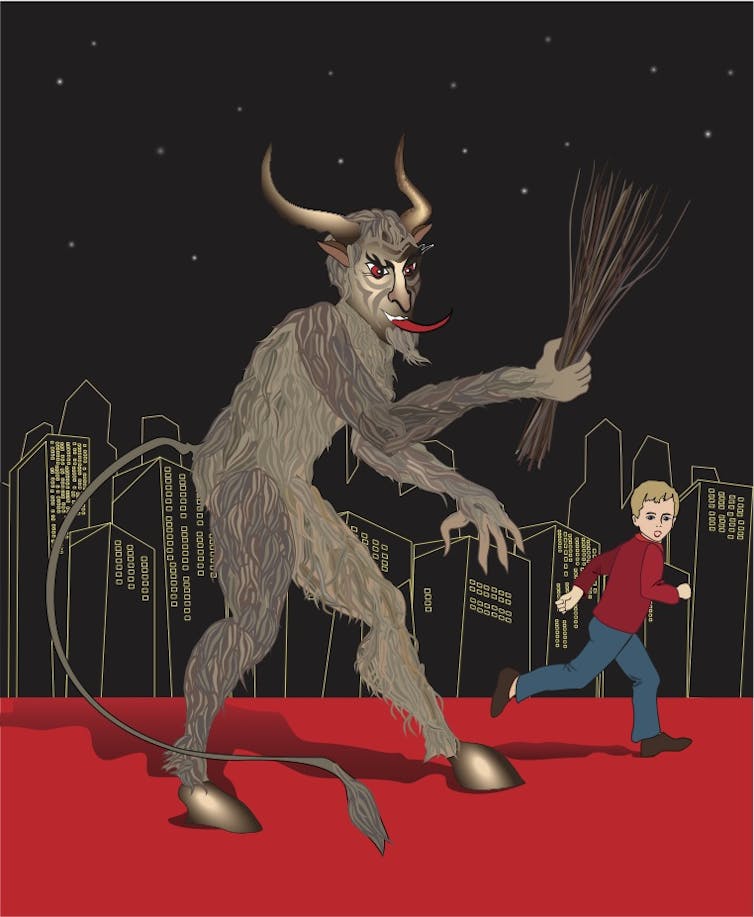

Central Europe: St Nicholas’ companion is a sinister creature that whips bad children

In central Europe, including Austria, Bavaria and the Czech Republic, the companion of St Nicholas is the sinister Krampus, a terrifying creature with fangs, horns and fur, who punishes naughty children by whipping them with sticks, called “ruten bundles”. These whippings are intended to make bad children good.

Those who cannot be whipped into niceness are put into Krampus’ sack and taken back to his den (somewhat akin to the Zwarte Pieten and Spain).

Also similar to the Zwarte Pieten is Krampus’ gift of coal, though he also gives ruten bundles (sticks sprayed with gold paint displayed in houses all year round) to remind children to be good throughout the year.

Krampus has pagan origins and is claimed to be the son of Hel, the goddess of the dead in Norse mythology.

The den to which he takes bad children is the Underworld, which literally means that if you are naughty you will die.

This pagan origin made the Christian churches in central Europe hostile to Krampus, in particular the Catholic Church, which banned rituals dedicated to him.

In the 21st century, as the influence of Christianity has receded, these traditions have been revived with great enthusiasm.

Groups of men dress as Krampus and rowdily parade through towns on Krampusnacht (December 5, before the feast of St Nicholas), drinking Krampus schnapps – a traditional fruit brandy brewed extra-strong for the occasion – and scaring children.

Some Krampuses bear more than a passing resemblance to Chewbacca, with horns! Krampus has now been immortalised in film, with “Krampus”, a horror comedy directed by Michael Dougherty, being released in 2015.

South Korea: a family occasion where it’s fashionable to attend a Christmas church service

South Korea has more Christians than many Asian countries and Christmas is a public holiday there, even though 70% of the population is not Christian.

Christmas trees abound, decorated with twinkling lights and often with a red cross on the top. Lavish Christmas displays in shop windows are common. It’s also a time of family celebration.

For many non-Christians, it has become fashionable to attend a Christmas church service, and groups of people walk through neighbourhoods singing Christmas carols.

Christmas cake (though not European-style fruit cake, but either sponge cake with cream, or ice-cream cake) is a popular seasonal indulgence. Christmas dinner, however, is firmly Korean and usually includes noodles, beef bulgogi and kimchi (pickled cabbage).

Santa Claus also features and is called Santa Kullusu or Santa Haraboji (Grandfather). He may sometimes wear a blue suit instead of a red suit, something that was common in the 19th century, when Santa Claus was often portrayed wearing blue or green, until red became the most popular colour.

Yet Christmas is not the great consumerist event that is common in the West; Koreans generally give one gift only to close friends and family.

New Year, which is a huge festival in all East Asian cultures, has far more extravagant celebrations. But Christmas is very popular with younger Koreans and is likely to become a larger part of cultural life in the future.

This article was originally published in The Conversation

Podcasts about Christmas traditions:

Articles you may also like

Would London Fire Brigades really let your house burn down if you were uninsured?

Reading time: 4 minutes

Here’s an interesting fact: if you didn’t pay your insurance premiums in 17th and 18th century London, firefighters would simply let your house burn, even if they were on the scene. This fact has been repeated many times by many people, so it must be true, right? Or is it?

General History Quiz 154

1. What group did Boudicca lead in her battles against the Romans?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

Weekly History Quiz No.223

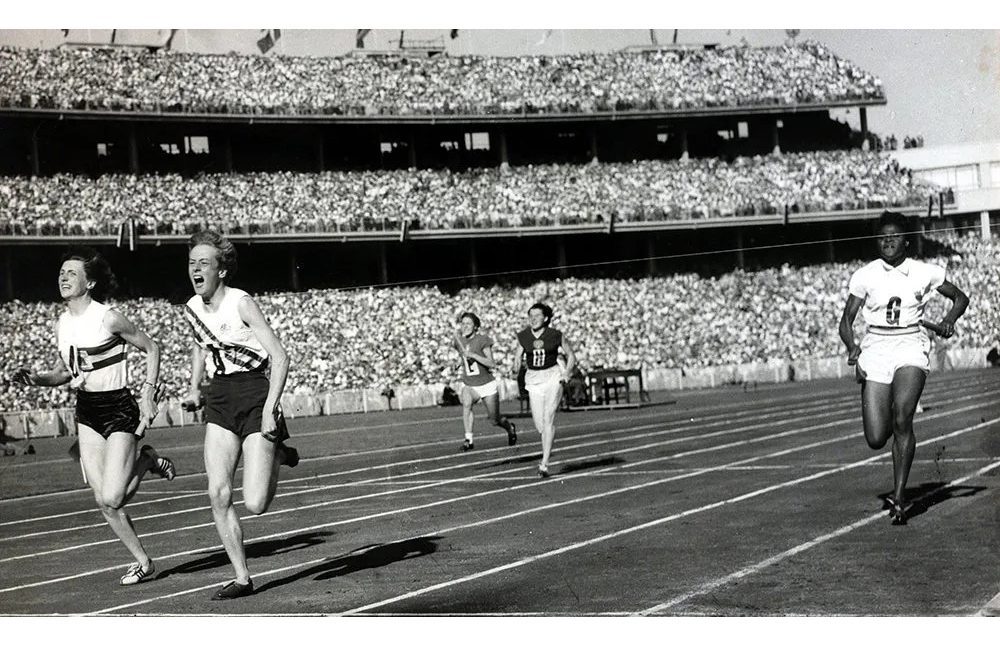

1. Where was the first Olympic games outside Europe and North America held?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.