Reading time: 7 minutes

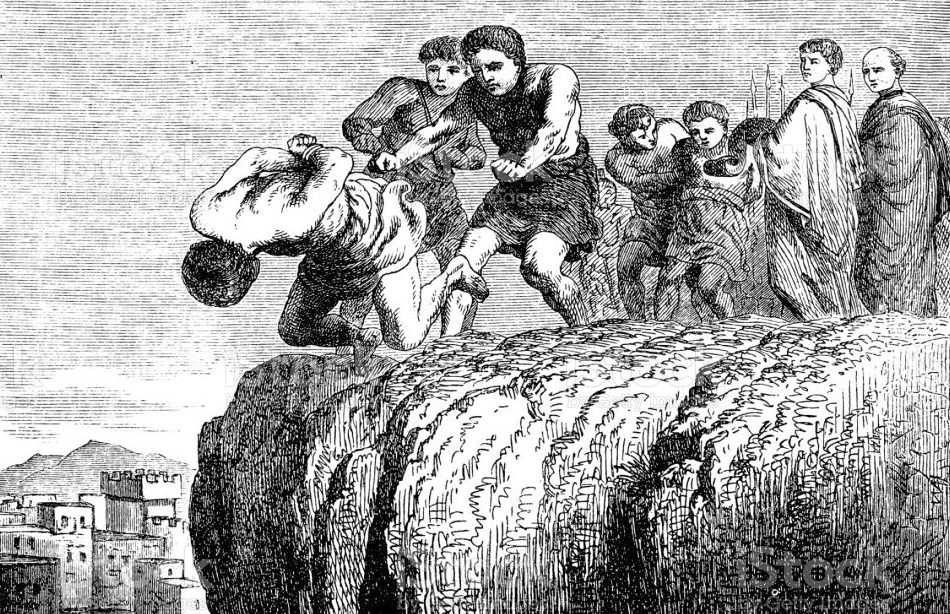

Early Roman history is full of stories about the terrible fates that befell citizens who broke the law. When a certain Tarpeia let the enemy Sabines into Rome, she was crushed and thrown headlong from a precipice above the Roman forum.

Such tales not only served as a warning for future generations, they also provided a backstory for some of Rome’s cruellest punishments. Tarpeia is one of many legendary figures who appear in Livy’s History from the Foundation of the City; regardless of whether she was a real person, it became established practice to throw traitors from the “Tarpeian Rock”.

However, not all of the cruel and unusual punishments we associate with the Romans were carried out in practice or uniformly enforced, and some changed significantly over time.

By Shushma Malik and Caillan Davenport, Macquarie University.

Obey thy father

Roman society was fundamentally hierarchical and patriarchal. A Roman paterfamilias (the family’s oldest living male) had, in theory, the power to kill someone within his household with impunity. This included not only those physically living under his roof, but the wider family of brothers, sisters, nieces, and nephews as well.

However, historians have debated whether the power may have been largely symbolic and little used in practice. Filippo Carlà-Uhink has argued that the power did exist, but didn’t give heads of the household carte blanche to act as they pleased. For example, the senator Quintus Fabius Maximus Eburnus is said to have killed his son for his “dubious chastity”. But punishing a crime of a sexual nature was not seen as the proper use of a father’s power, so Quintus himself was tried and exiled.

In order for the use of such power to be justified, the son had to have committed a crime against the state. When Aulus Fulvius was killed by his father for his involvement in the conspiracy of Catiline (63 BC), the head of the household was not prosecuted. This was because Catiline and his followers had committed treason by plotting to murder the consul Cicero and seize power for themselves.

A watery and crowded grave

One of the most pervasive misconceptions about Roman criminal justice concerns the penalty for parricide. Anyone who killed his father, mother, or another relative was subjected to the “punishment of the sack” (poena cullei in Latin). This allegedly involved the criminal being sewn into a leather sack together with four animals – a snake, a monkey, a rooster, and a dog – then being thrown into a river. But was such a punishment ever actually carried out?

The epitome of Livy’s History from the Foundation of the City records that in 101 B.C.:

There is no mention here of any animals in the sack, nor do they appear in contemporary evidence for legal procedure in the late Roman Republic. In 80 B.C., Cicero defended a young man called Sextus Roscius on a charge of parricide, but the murderous menagerie is conspicuously absent from his defence speech.

The animals are attested in a passage from the writings of the jurist Modestinus, who lived in the mid-third century A.D. This excerpt survives because it was later quoted in the Digest compiled at the behest of the emperor Justinian in the sixth century A.D.:

The penalty of parricide, as prescribed by our ancestors, is that the culprit shall be beaten with rods stained with his blood, and then shall be sewed up in a sack with a dog, a rooster, a snake, and a monkey, and the bag cast into the depth of the sea, that is to say, if the sea is near at hand; otherwise, he shall be thrown to wild beasts, according to the constitution of the Deified Hadrian.

The snake and the monkey feature in the satirical poems of Juvenal (writing during the age of Hadrian), who suggested that the emperor Nero deserved to be “sacked” with multiple animals for murdering his mother Agrippina. But the dog and the rooster do not appear until the third century A.D., when Modestinus was writing.

The punishment fits the (Roman) crime

So was anyone ever actually punished with all these creatures? The emperor Constantine’s penalty for parricide only specified that snakes should be added to the sack. Parricides were commonly punished in other ways such as being condemned to the beasts, which was very popular in the Roman world.

Many historians have thought that the practicalities of sewing up a dog, a monkey, a rooster, a snake, and a human in a sack together indicates that the penalty was never actually enforced – for one thing, it would be as much a punishment for the executioners as it would for the condemned.

The Romans themselves believed the poena cullei was an ancestral custom – but as with many customs, it was based on preconceptions about the nature of ancient punishments. The best-known version of the penalty for parricide, with all the ferocious fauna included, was a product of the later Roman empire. It was designed to terrify, rather than to be enforced.

The poena cullei entered the standard accounts of Roman criminal law because it fascinated medieval scholars who tried to identify the symbolism of the animals. Florike Egmond has shown that this inspired the introduction of the sack filled with creatures as a punishment in Germanic law, reflecting the belief that a civilized society should follow Roman judicial practices.

To the relief of Germans in the medieval and early modern period, such punishments were rarely carried out. On one occasion, images of the animals were sewn into the sack, as they were considered sufficient substitutes for the real thing.

Thinking of dodging the census?

Taking part in the Roman census was compulsory as the state needed a complete record of citizens’ property for tax purposes. According to the first-century B.C. historian Dionysius of Halicarnassus, the sixth king of Rome Servius Tullius decreed that anyone who did not participate in the census would lose their property and be sold into slavery.

But questions remain over whether this punishment actually happened – Dionysius was writing centuries after the sixth king’s reign, and Servius Tullius was probably fictional anyway. Dionysius’ contemporary, Livy, records a different penalty – citizens who failed to register were threatened with death and imprisonment.

There is no recorded example of either penalty being enforced. Ancient historian Peter Brunt has proposed that this may have been because Romans always turned up to be registered in order to ensure that their rights as citizens would be guaranteed. It’s worth noting, however, that neither Dionysius nor Livy suggested that the law was still in use in their own time – the harsh punishments may have reflected a later conception of cruelty in early Rome, rather than any historical reality.

Writing in the late Republic, the famous lawyer and politician Cicero states that one man, Publius Annius Asellus, decided not to present himself at the census in order to circumvent an inheritance law – and he only lost the right to vote. The Roman authorities had bigger problems as they were rarely able to carry out the census effectively in the first century B.C. (the first #censusfail). Besides, if you were fighting abroad, living outside of Italy, or unable to travel owing to extreme poverty, the Romans in charge could be quite lenient.

The penalties of census slavery, the power of the father, and the punishment of the sack reflect the Romans’ own conception of their ancestors and the idea that authorities must impose harsh penalties in order to deter offenders. But we need to be careful in reconstructing the histories of such punishments. As the case of parricide shows, the versions we are familiar with today are often a collage of sources from different periods assembled to create one specific punishment that seems authentically “Roman”.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Articles you may also be interested in

The Empresses of Rome – Audiobook

THE EMPRESSES OF ROME – AUDIOBOOK By Joseph Martin McCabe (1867 – 1955) The story of Imperial Rome has been told frequently and impressively in our literature, and few chapters in the long chronicle of man’s deeds and failures have a more dramatic quality. The fresh aspect of this familiar story which I propose to consider […]

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.