Reading time: 5 minutes

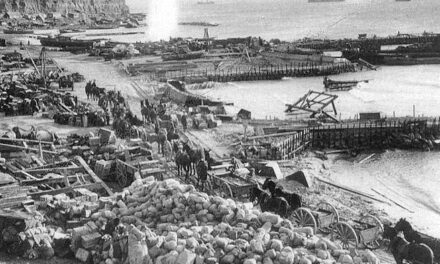

The vivid and graphic imagery of the First World War has indeed become a potent symbol of the need for everlasting commemoration, and a continuous reminder of armed conflict’s futility. Yet with the inevitable passing of time, direct links to the “War to end all Wars” have regretfully vanished, with all veterans who served in the trenches now gone. This most special group of soldiers may now be physically silent, but their haunting messages of warning remain.

By Michael Vecchio

As another anniversary of the 1918 Armistice approaches, it remains ever pressing to hold these warnings dear, as war continues to have a devastating effect on our modern world. And so it is once more that a voice from the past persists in a most urgent manner in the present. One of the Great War’s most effective messengers of distress finds his cry newly resurrected in our contemporary times.

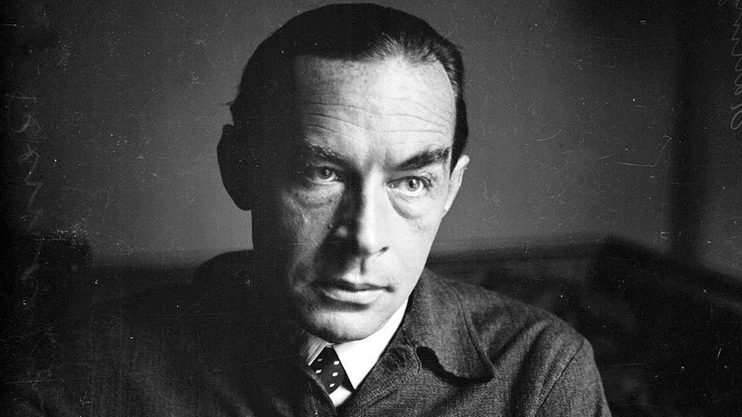

Erich Maria Remarque (1898-1970) was just a 19-year-old boy, who in the midst of the depravity of battle constantly faced the reality of never getting to experience manhood. Yet through his direct experiences with death and destruction, the very youth that he and millions of other soldiers innocently brought to the trenches, was indeed left behind. When he documented his own story in the semi-fictional novel All Quiet on the Western Front in 1928, a damning and horrific portrait emerged of the sheer absurdity of war.

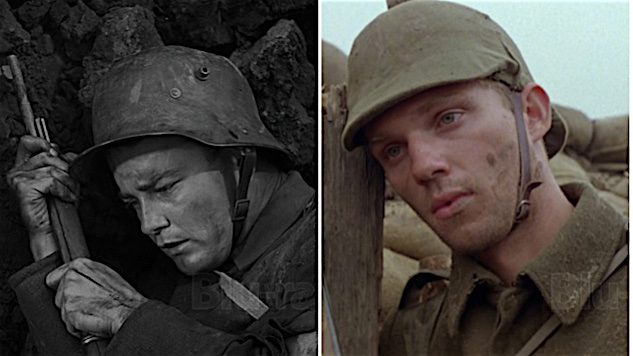

Now in 2022, this narrative once more gets the film treatment in director Edward Berger’s adaptation. The third such film on Remarque’s novel after the 1930 and 1979 films, (and the first to be an all-German production), this newest version is another visceral, upsetting, distressing, and ultimately cathartic experience that implores us to never forget. Indeed, in addition to this film’s raw and brutal images, what makes this story (and in turn its other adaptations) even more compelling is its unique German lens.

For so long the narrative of the Kaiser and his army as the War’s “villains” persisted; in fact the harsh punishments inflicted on the German state in the post war period (particularly the Treaty of Versailles) led only to further humiliation. With Remarque’s novel, it was precisely the experience of German soldiers that informed his perspective, but that ultimately revealed itself to be a most universal viewpoint. The horrid conditions of the trenches and the vast battlefields of slaughter were not solely a German experience, or a French and British one, or Russian or Ottoman, but of all combatants. Thus the brilliance of Remarque’s work is not only that it humanizes the so called “antagonists” but provides a most universal and damning commentary on war’s utter uselessness.

In this newest film adaptation, viewers are brought on a most graphic and barbaric journey. Though it is seen through the eyes of a young German soldier, the colours of the uniform do not ultimately provide any sense of immunity. Instead a portrait of state sanctioned insanity is presented, where millions are sent to a certain death in the name of a most perverse sense of glory for the fatherland. Where director Edward Berger deviates from the source material is only in his addition of the behind the scenes negotiations held to reach an uneasy peace.

READ MORE: THE MOST LOVED AND HATED NOVEL ABOUT WORLD WAR I

Featuring bleak and explicit cinematography, the utter horror of combat is not sanitised for viewer’s eyes. Chosen as Germany’s selection for Best International Film at the 95th Academy Awards, the film does not stumble in its frank and hellish portrayal not just of the battlefield, but of the perverted obstinance of high command.

Aiming to create an informative frame around the scenes of unending chaos, this 2022 version sidesteps some of our main character’s story, in favour of a more general viewpoint of a soldier’s suffering. Indeed Remarque’s novel and the previous film versions focus more on the experience of soldier Paul Baumer, particularly his training and brief return home, where this new film keeps the action almost completely on the battlefield.

Still Edward Berger, and fellow filmmakers Lewis Milestone and Delbert Mann, who directed the 1930 and 1979 adaptations respectively, all channelled Remarque’s frank and unflattering tone. The cost of claiming but a few yards of land was the massacre of a generation.

I see how peoples are set against one another, and in silence, unknowingly, foolishly, obediently, innocently slay one another.

Erich Maria Remarque

The central theme of All Quiet on the Western Front, the novel, and its cinematic adaptations is; no amount of perceived territorial gain or patriotic glory can ever justify a direct encounter with bloodshed. For many of these soldiers did indeed leave as boys but would not return as men. And so, Erich Maria Remarque’s extraordinary testimony continues to prove its everlasting relevance today.

Through his most remarkable literary work and the very affecting film versions, including this 2022 adaptation, Remarque’s lamentable tale persists in having raw effects on all who heed the warning. November 11th approaches once more, but will the guns really stop firing? Or is it part of our human inclination to kill, despite all the ominous alarms of the past.

Indeed as the British poet and fellow soldier Wilfred Owen wrote in his own work:

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungsMy friend, you would not tell with such high zest

Wilfred Owen

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori (It is sweet and proper to die for one’s country)

In All Quiet on the Western Front, we have an important document of remembrance, admonition, and despair, in the hope that perhaps one day November 11th will indeed be the first day of endless days of peace.

Podcast episodes about All Quiet on the Western Front

Articles you may also like

What lies behind the war in Tigray?

Reading time: 7 minutes

At the core of the current war between the Ethiopian central government and the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front is the realignment of politics and the contest for political hegemony. In my view, it is about Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed allying with the Amhara to destroy Tigrayan power. This is an attempt to consolidate his position and that of his Amhara supporters.

Northern Ireland, born of strife 100 years ago, again erupts in political violence

Sectarian rioting has returned to the streets of Northern Ireland, just weeks shy of its 100th anniversary as a territory of the United Kingdom. For several nights, young protesters loyal to British rule – fueled by anger over Brexit, policing and a sense of alienation from the U.K. – set fires across the capital of […]

What Vietnam and Iraq should teach Canberra

Reading time: 7 minutes

If we learn more from losses than wins, then the Canberra system has much to gain from examining its lousy performance in the processes that took Australia to war in Vietnam and Iraq. For Australia, both wars were all about the alliance with the United States. Both were wars of choice, although the regional implications Canberra read into Vietnam meant it was closer to a war of necessity than Iraq.

Both wars exemplify the Prime Minister’s most profound prerogative and Parliament’s lack of power. The entry to both showed the Canberra system performing below its best, revealing again the truth that artifice and farce often attend the most serious of moments of government.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.