Reading time: 8 minutes

Our knowledge of the ancient world owes a lot to chance discoveries. Here, we share the stories of some of the most important and unlikely finds from ancient Western history.

By Claudia Hooper, University of Melbourne

Unearthing a secret scroll, tablet, stone or parchment filled with important revelations about the past is an archaeologist’s dream.

Chance finds, like the Dead Sea Scrolls – which contain some of the oldest known manuscripts of the Hebrew Bible and were discovered by Bedouin shepherds – have shed unique light on life and thought in ancient times.

Here, we ask University of Melbourne classicists, historians and archaeologists to list some of the most important of these fortunate discoveries and the stories behind them.

They range from the keys to forgotten scripts from Ancient Egypt and the time of Troy, to lost poems, philosophies and even a legal text book. We owe their preservation not only to luck, but to the fastidious and obsessive geniuses who uncovered and deciphered them.

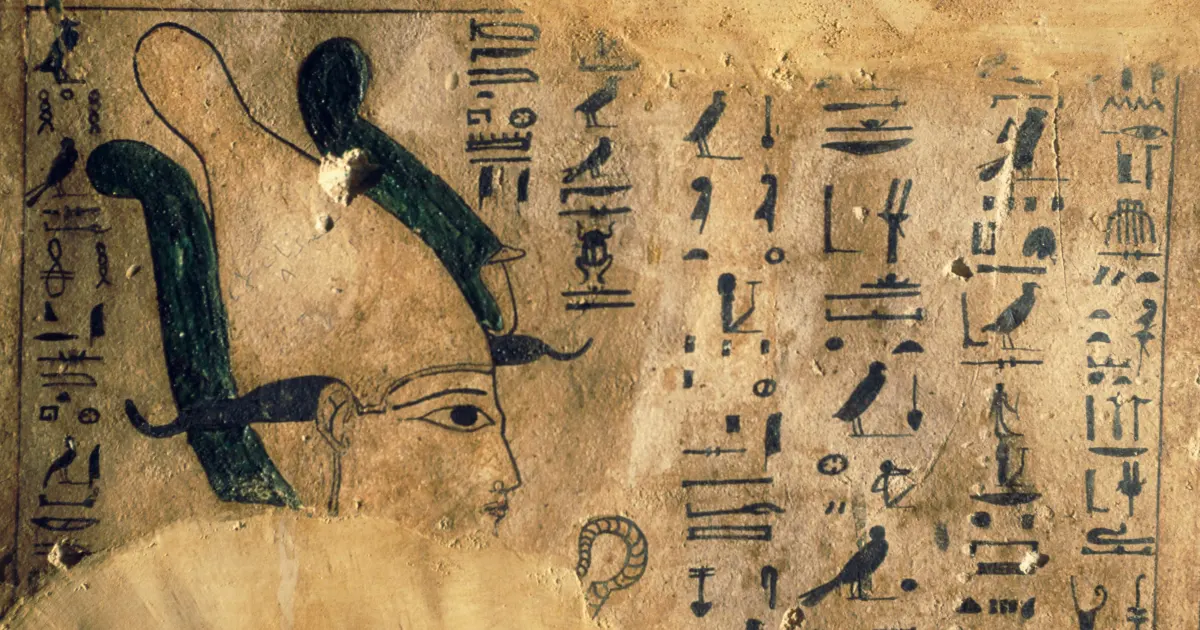

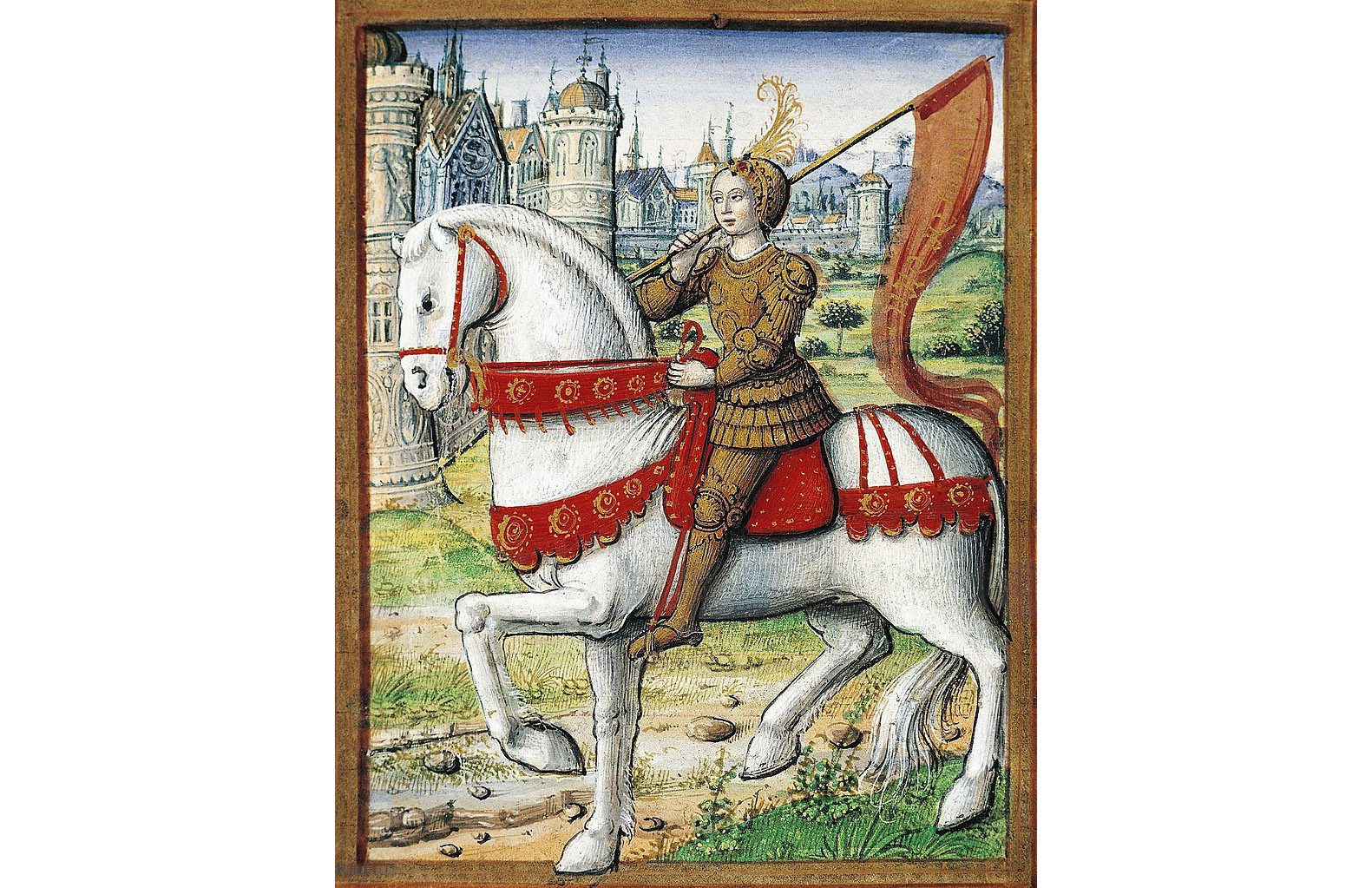

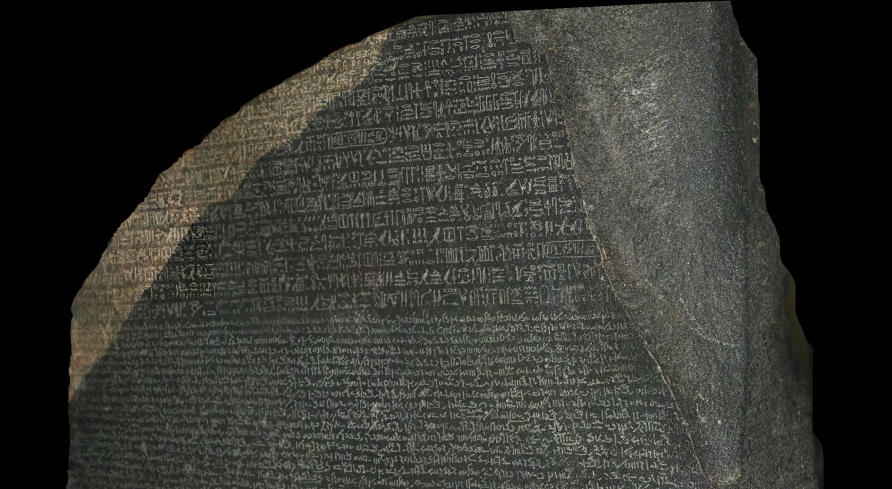

DR BRENT DAVIS: THE ROSETTA STONE

The story of the Rosetta Stone starts with Napoleon Bonaparte, who invaded Egypt in 1798 on one of his many campaigns to become master of the world.

In 1799, a group of French soldiers working near the town of Rosetta in the Nile Delta tore down an ancient Egyptian wall so they could use the stones to repair a French fort. One of these stones was the Rosetta Stone, an inscribed slab of granite now in the British Museum.

The stone is inscribed in three different scripts: the top section is in full hieroglyphs, the middle section is in Demotic (a cursive form of hieroglyphs), and the bottom section is in Greek which, of course, could easily be read.

Scholars quickly realised that the stone contains the same text written three times, once in each script.

Everyone saw that this stone might unlock the secret of hieroglyphs—as indeed it did. In 1822, the brilliant French scholar Jean-François Champollion made a major breakthrough in deciphering the hieroglyphic portion, giving birth to the modern field of Egyptology.

PROFESSOR TIM PARKIN: THE INSTITUTES

The Institutes, a legal textbook written by the Roman jurist Gaius in or around 161 CE, is the most substantial legal work to survive from the time when Roman law was at its height as a science.

It is one of the most important sources for understanding how Roman society actually worked, but Gaius’ work had all-but disappeared until a chance discovery in 1816.

The Danish-German statesman, banker, and historian Barthold Georg Niebuhr was searching through Christian manuscripts at the cathedral library in Verona when he noticed that a legal text had been partly scrubbed out on the parchment and overwritten with the Epistles of St Jerome.

The palimpsest proved to be an almost complete version of Gaius’ Institutes – some 250 pages of Latin text.

The work is vitally important for legal scholars because it fills in a gap of more than a millennium in our knowledge of Roman law. To this day Gaius is required reading for students of Roman law (and indeed, in some universities, for all law students).

But it is also hugely important for historians because in the Institutes Gaius observes how the law worked in reality in the second century AD.

For example, noting that a woman whose father has died is legally subject to a male guardian irrespective of her age (unlike a man who became independent from age 14 years), Gaius observes that the law is silly because women are just as capable as men and that the law was often ignored in practice anyway.

For my work on ancient Roman society, Gaius is one of the single most important texts to have come down to us.

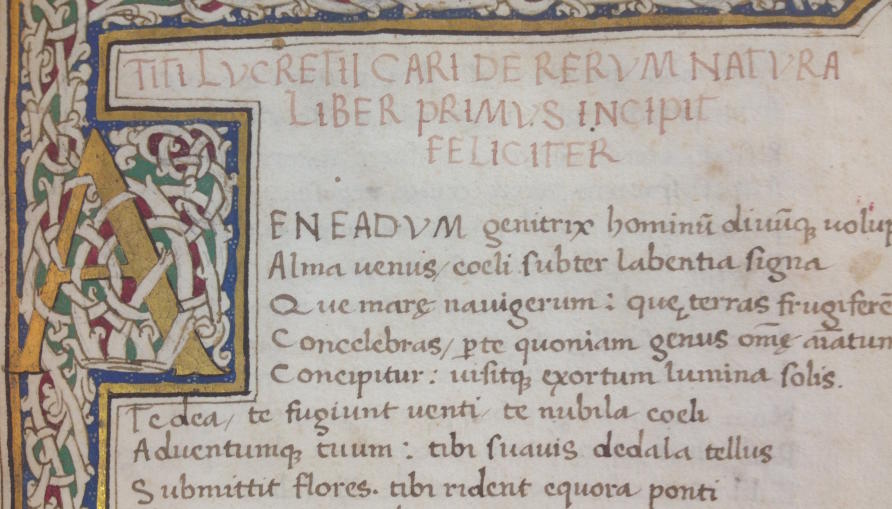

DR JOHN WILKINS: DE RERUM NATURA

In 1417, Gian Francesco Poggio, a papal secretary, was hunting for ancient manuscripts in a German monastery when he found a ninth century copy of the Roman poet Lucretius’ De Rerum Natura (On the nature of things).

The long, six-volume poem was at once heretical and revolutionary because it preserved key parts of the lost thought of ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus, whose reputation at the time was as a glutton and atheist.

Indeed, Epicurus’ name had even become the Hebrew word for atheist.

Lucretius’ poem discussed the nature of the physical world, including atomism (the idea that everything is made up of very small objects ), the creative role of chance events and the complete lack of interest by the gods in anything that might happen in the physical world.

It was clearly dangerous stuff, but by writing careful forewords to Poggio’s discovery disavowing Epicurus, scholars were able to spread Lucretius’ work without getting themselves tied to a pyre.

While it turns out that other libraries had copies of De Rerum Natura, at the time of Poggio’s discovery the ideas in the poem, while not exactly forgotten, had been suppressed.

The preservation and dissemination of Lucretius’ work would inspire both philosophers and painters, and go on to influence many early modern thinkers and naturalists as modern science emerged from the Middle Ages.

Without Lucretius’ influence, neither the Enlightenment, nor modern science, may have been possible at the times they happened.

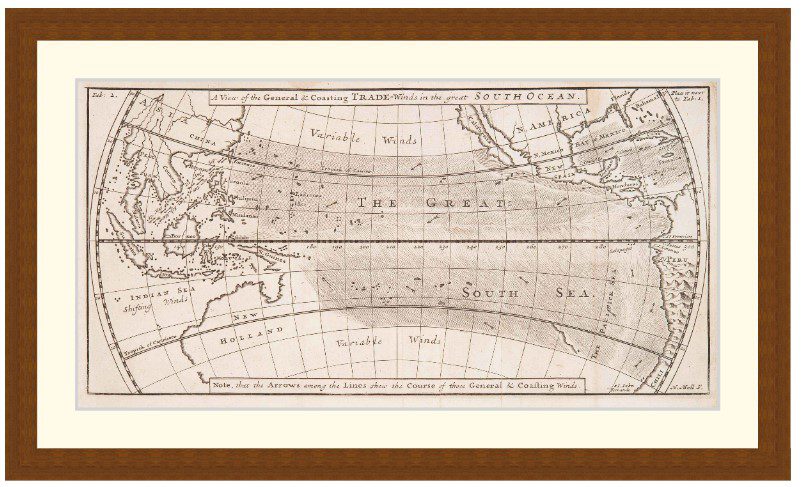

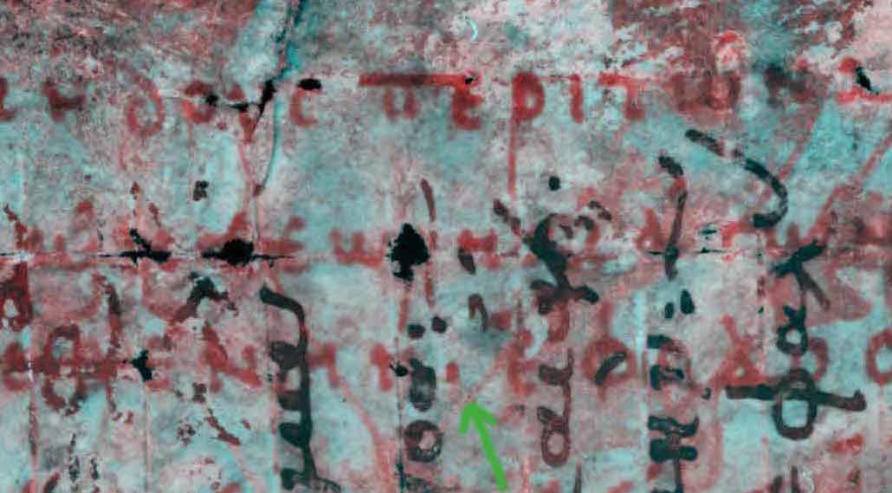

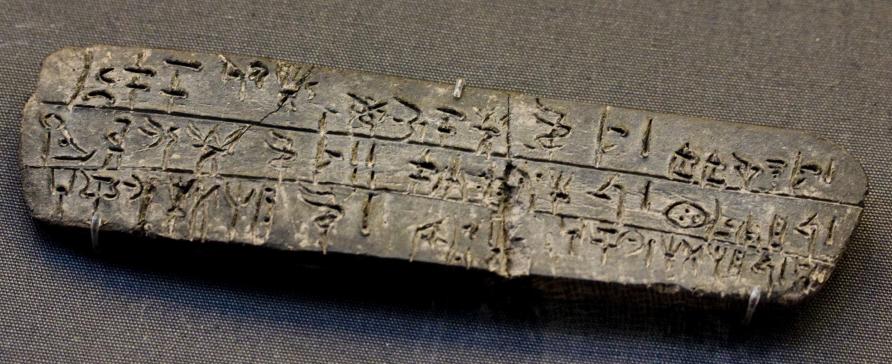

PROFESSOR LOUISE HITCHCOCK: LINEAR A AND B

One of the last frontiers in the discovery and decipherment of ancient texts are the Aegean scripts Linear A and Linear B. These are the scripts of the Minoan, Cypriot and Mycenaean civilisations of ancient Greece – Homer’s Age of heroes.

The decipherment of Linear B, an early form of Ancient Greek preserved mostly on clay tablets, was dramatically announced in a famous 1952 radio announcement on the BBC by architect and war time codebreaker, Michael Ventris.

As a fourteen-year-old, young Ventris had heard Sir Arthur Evans – the discoverer of the Knossos palace on Crete fabled as the home of the Minotaur – present a lecture on the Linear B texts, and made it his lifetime dream to decipher it.

Linear B dates to the era of Mycenaean palaces around 1500 to 1200 BCE, and pushes the study of classical languages back into the Bronze Age, the time before the Trojan war.

However, these are not texts recording events or deeds by famous people. Rather they are temporary administrative palace documents consisting of allocations of goods or labour to the likes of smiths, temples, ships, cloth workers, and chariot makers. They give us valuable insights into the structure of the Mycenaean political system, as well as trade, manufacturing, and the economy.

But the language written in the earlier Linear A script is yet to be deciphered.

It originated on Crete initially as a hieroglyphic or pictographic script around 1900 to 1700 BCE and is preserved on clay tablets, stone libation tables, gold jewellery and even on magic bowls inscribed with octopus ink.

DR JAMES H.K.O. CHONG-GOSSARD: SAPPHO’S POEMS

“My knees, that were once swift for the dance like little fawns, do not carry me. I lament this often, but what can I do? To be ageless when one is mortal, is not possible.”

So writes the incomparable ancient Greek poetess Sappho in the late 7th century BCE in the “Tithonus poem”, a gem of only twelve lines that speaks to us across centuries of the sadness of ageing.

But fragments of the poem had long been lost, including these beautiful lines, and it is only because of a material similar to papier-mâché that they have been preserved for publication in 2004.

The original fragments of the poem had survived on papyri from 2nd to the 3rd century CE Roman Egypt, and had been unearthed at Oxyrhynchus in the early 20th century.

But, in 2002, the Cologne Papyrus Collection acquired from a private collector papyri that preserved the rest of Sappho’s poem.

These missing fragments had survived as “cartonnage” – a hard material comprising papyri, linen and plaster that was used in ancient times as book covers and mummy cases.

Another rediscovered Sappho poem first published in 2014, the “Brothers Poem,” was similarly preserved in cartonnage and was only uncovered when the papyrus fragments were separated by dissolving the cartonnage in warm water.

Some 2,600 years ago, Sappho lamented that people cannot be ageless, but the continual re-discovery of her words is proving the agelessness of her poetry.

This article was originally published in Pursuit

Podcasts about accidental archaeological discoveries

Articles you may also like:

General History Quiz 198

1. What was the codename given to the 1940 Dunkirk evacuation?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

Christmas History Quiz 2024

1. Where did the custom of decorating a Christmas tree originate?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

The text of this article is republished from Pursuit in accordance with their republishing policy and is is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivatives 3.0 Australia (CC BY-ND 3.0 AU).