Reading time: 7 minutes

In 1352 the crime of treason was defined for the first time in English law. But how were traitors punished in the pre-modern period? In this blog, I’m going to explore some of the more unusual, symbolic and grisly executions of traitors, but also the ways in which royal mercy could pardon traitors.

Hanged, drawn, and quartered

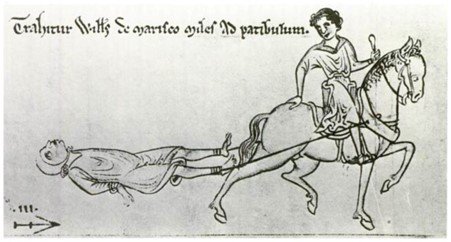

The main hallmark of the execution of traitors was for the individual to be drawn (dragged) to the place of their execution. The first known image of this comes from the 1242 execution of one William de Marisco, implicated in an attempt on Henry III’s life. The image shows him being dragged behind a horse to his execution.

A hurdle (similar to a sled) was later introduced in order to ensure the traitor did not die on the way. It was at the end of the century, however, with the trial and execution of Dafydd ap Gruffydd, when the symbolic – and almost ritual – execution of traitors would be used in the form familiar to us today: hanged, drawn, and quartered.

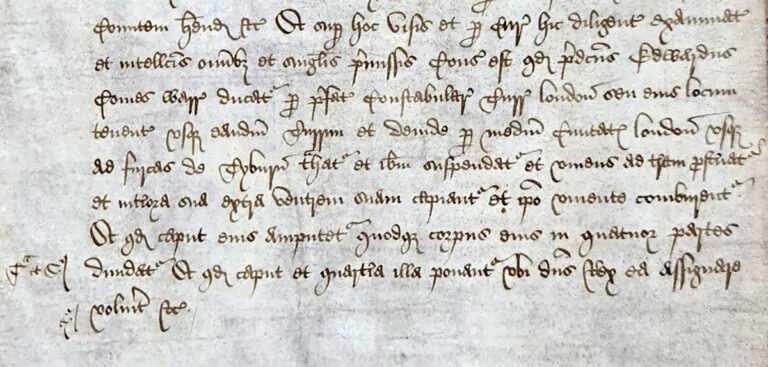

The severity of Dafydd ap Gruffydd’s punishment was almost certainly influenced by Edward I’s anger against the Welsh prince, who had rebelled against him, and each form of his execution was linked to specific crimes. For betraying the king he was to be drawn at the horse’s tail to the place of execution. For killing certain English noblemen, he was to be hanged alive. For committing murders during Easter, he was to be disembowelled (while still alive) and his entrails burned. For plotting the king’s death in different parts of the realm, he was to be quartered and the quarters despatched around the realm to act as deterrents. This was designed to be brutal, and a warning to all those who might consider rebellion against the king, particularly in those locations where the quarters were sent.

A similar symbolic form of execution would be seen in the execution of William Wallace a few decades later, setting a clear precedent for the future execution of traitors. It was not entirely fixed – disembowelling and castration were often, but not always included – but the process of drawing to the execution site, hanging the traitor until they were nearly dead, beheading and quartering were now fixed as the means of executing a male traitor. Women were instead burned to death (a practice which would remain in law until 1790).

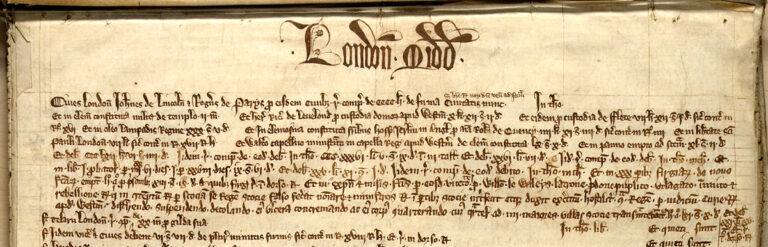

Many of the records in our collection contain details of the sentencing of traitors, often with the marginal annotation ‘T & S’ (referencing the Latin ‘Trahatur et Suspendatur’) recording that a traitor was sentenced to be drawn and hanged, including that of Edward, Earl of Warwick .

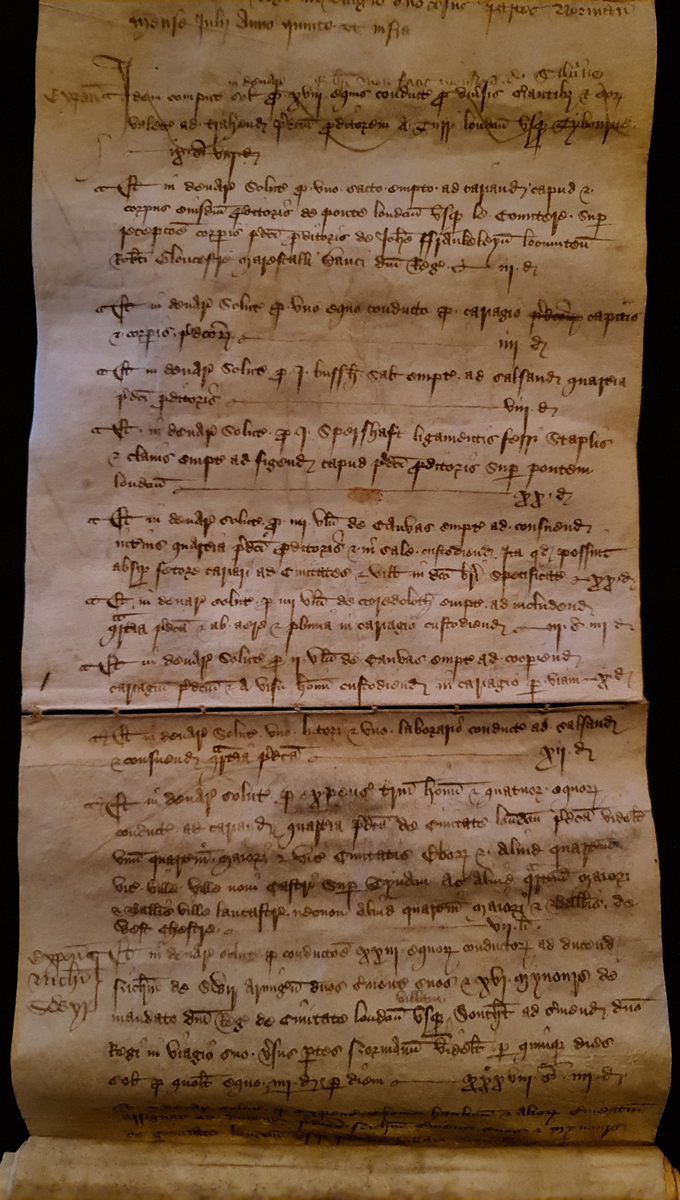

Others, however, record more extensive details. This Exchequer account includes detailed payments made for taking the quartered limbs of a traitor, Henry Talbot, to their intended destinations around the country in 1417. They include a bushel of salt (approximately 30kg) for preserving the limbs, a spear-shaft for fastening Talbot’s head on London bridge, bags and canvas to wrap the limbs in to avoid the stench, and a canvas to cover the carriage so those they passed would not see what was inside.

New forms of execution

The symbolism of a treason execution could also take more unusual forms. The execution of Sir John Oldcastle in 1417 linked two separate forms of execution in symbolic fashion once again. Oldcastle was a lollard, a religious reform movement which spread in the early 15th century , and which was the subject of regular crackdowns by the Lancastrian regime. As a religious movement, the lollard movement was faced by charges of both heresy and treason. Oldcastle’s execution combined both charges. For his treason he was drawn to St Giles’ Field, London (the scene of his abortive rising of 1414), where a gallows had already been erected. Suspended by an iron chain, he was then simultaneously hanged and burned (the traditional means of execution for heresy), as ‘a heretic and traitor to God and the king’, thus ‘paying the penalty of both swords’.

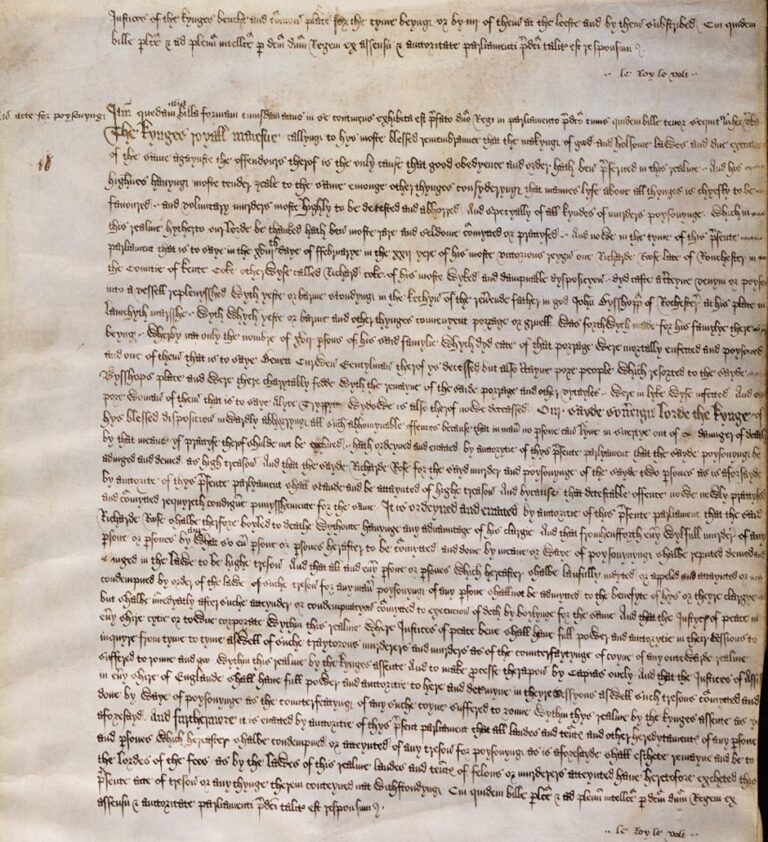

Perhaps the most symbolic and gruesome execution for treason was that of Richard Roose in 1531. Roose had been charged with a new form of treason, attempting to poison the porridge of the Bishop of Rochester, with a new form of execution also introduced in relation to the crime. For poisoning, Roose (and any future poisoners) was to be boiled to death in Smithfield, London, his body placed in a gibbet and symbolically lifted in and out of the water to represent the act of placing the poison in the porridge. This was a visceral, public and horrendous act, intended to act as a powerful disincentive for any would be poisoners.

It would later be repealed by Edward VI (r. 1547–1553) at the start of his reign, along with many other expansions of treason by Henry VIII. You can find out more about Roose and his execution in this thread on our Twitter feed.

Power of the pardon

Violent and symbolic punishments and executions could sometimes be contrasted with displays of royal mercy or mitigation. Noblemen often had their sentence mitigated to beheading, rather than being made to suffer the full horror of the traitor’s death. Anne Boleyn – in probably one of the best known stories of mitigation – had her sentence altered at the request of Henry VIII, from being burned to death to beheading.

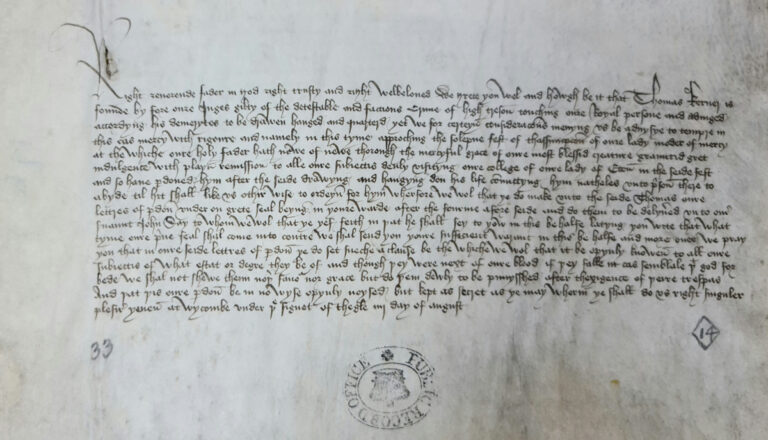

More unusual was the last-minute pardon given to a more obscure figure in the 15th century. Thomas Kerver, a gentleman from Reading in Berkshire, was charged with uttering treasonous words against Henry VI in the precinct of Reading Abbey in 1444, stating that it the realm would have been £100,000 wealthier had the king died twenty years earlier when he was young. Kerver’s alleged crimes were investigated twice in order to try and secure a conviction on all counts.

Eventually sentenced to the usual traitor’s death, Kerver faced execution, but was saved by a last-minute pardon by the pious king on account of the fact it was almost the feast of the Assumption, a feast day when those visiting nearby Eton College could receive papal indulgences. He was not, however, entirely free. The letters which authorised Kerver’s pardon stated that he should be drawn through Berkshire to the gallows, hanged until he was nearly dead, and only then told of his pardon. This was a calculated gesture of mercy, allowing the visual warning to those who might consider uttering similar words that would come from seeing the traitor drawn and hanged, while sparing the bloodshed involved.

Podcasts about treason and torture in the Middle Ages:

Articles you may also like:

Hard Fought: Australia In The Mediterranean Theatre 1940-1945 Conference

Reading time: 3 minutes

History Guild is supporting a conference examining the part played by Australian’s in the Mediterranean theatre of WW2. This conference is presented by Military History & Heritage Victoria in Melbourne, Australia on the 9th and 10th of April 2022. It will be held in person and features a conference dinner on the 9th of April. History Guild is subsidising conference registration fees for students and early career researchers. This will allow more history students to study and research this important part of Australian history.

This article was first published by The National Archives. It is reproduced in accordance with the Open Government Licence v3.0.