Reading time: 6 minutes

When the 2020 Olympic Games in Tokyo were canceled due to the COVID-19 pandemic, it was only the fourth time that international events prevented the games from going forward. Perhaps surprisingly, this was the second time for Tokyo, although 2020 was ultimately postponed a year rather than canceled

By Paul Droubie

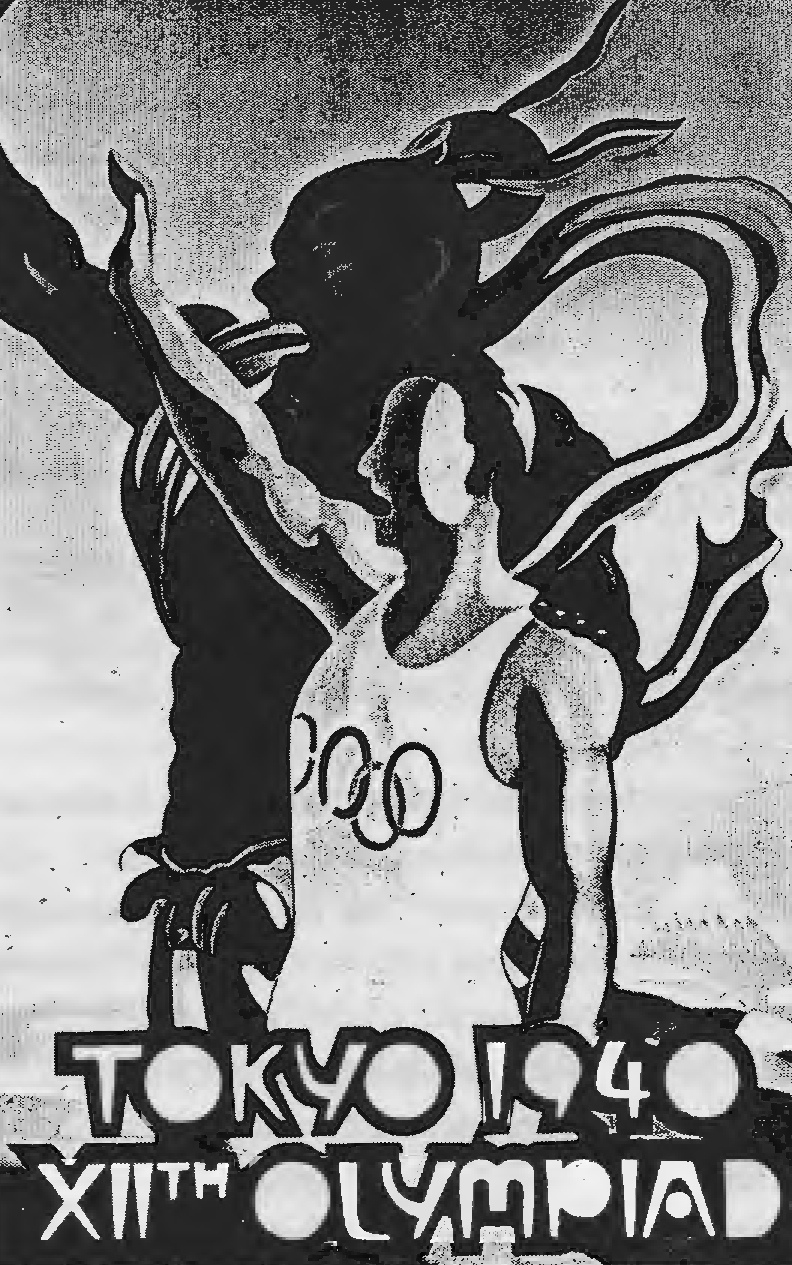

The 1940 Tokyo Summer Olympics, which disappeared like a fantasy to its Japanese supporters, are sometimes referred to as the “Phantom Olympics.” They were to be the first games hosted by a non-Western country and the culmination of years of advocacy, beginning in 1930, by Japanese officials. Along with the 1916 and 1944 Olympiads, the 1940 games are one of only three canceled Olympiads, all due to war. While the 1940 Olympics were ultimately canceled, and the 1940 Tokyo Olympics are described as “canceled,” this is not technically true. The Tokyo games were forfeited when the city, because of issues impacting Japan, voluntarily relinquished its right to host the games. This decision was the product of both conflicting ideological impulses—between nationalism and internationalism—at the core of Tokyo’s bid for the games and material needs related to Japan’s war in China.

Hosting the games in 1940 was as much an ideological project as it was a major sporting event. Domestically, 1940 was an important year for Japan. Large-scale celebrations were planned to mark the 2600th anniversary of the accession of Emperor Jimmu as Japan’s first emperor and the mythological start of the Japanese nation-state. On one hand, these celebrations served to unite the Japanese people through nationalism and loyalty to the state at a time when conflict spread across East Asia. This was especially critical in the years following the 1931 Manchurian Incident, a false flag operation that marked Japan’s seizure of Manchuria, and Japan’s withdrawal from the League of Nations a year later. On the other hand, as historian Sandra Collins has argued, Japanese organizers also saw hosting the Tokyo Olympics as a way to conduct “people’s diplomacy” and “sports diplomacy.” These diplomacies were a valuable part of the games, given growing international criticism of Japan’s actions in Manchuria and increasing isolation from more formal diplomatic venues. They hoped “people’s diplomacy,” which the Olympics proclaim to practice on a person-to-person basis through sports, would show the “real” Japan to Westerners and reduce tensions. As either a nationalist or internationalist project, the Olympics became tied to nationalistic beliefs about the strength and superiority of the Japanese nation.

Tying the Olympics to the anniversary of the Japanese nation, as the games’ advocates did, created tension that was difficult to resolve. Japanese representatives increasingly argued that Japan represented a uniquely modern, yet ancient society, an ongoing trope in Japanese national identity that would also be evident in the nation’s successful bid for the 1964 Summer Olympics. In so doing, they appealed to both Japanese nationalism and Western Orientalism. While the former created increasing tensions with the global community, the latter worked in Japan’s favor.

Hosting the Games in 1940 was as much an ideological project as it was a major sporting event.

Japan’s 1940 Olympic planning fell victim to the fractured and factional nature of Japanese political power, as various government ministries, International Olympic Committee (IOC) members, sports officials, and the city of Tokyo all vied for influence on the Olympic Organizing Committee (OOC). In an era marked by increasing centralization of authority and power in the name of nationalism in Japan, the OOC included multiple members associated with the military. From the start, the OOC emphasized presenting Japanese national identity, tied to the 2600th anniversary of the ascension of the first emperor, while avoiding frivolous excesses that they associated with the West. The IOC became alarmed by what they saw as misuse of the Olympics as a stage for Japanese nationalism. This delayed the creation of the OOC until the very end of 1936, increasing IOC fears that preparations were behind schedule.

Internal conflicts only increased after Japan invaded China in 1937, in what the Japanese euphemistically called the “China Incident,” and the war fueled demands to funnel resources to the military. A June 1938 austerity plan to reallocate financial and material resources to the war in China meant there would be little funding available to the OOC. This meant there would not be sufficient funds or resources for venues, infrastructure, and ongoing costs. Despite limited finances, Japanese supporters of the Olympics argued that the games should continue as planned, since they could be used to counter growing Western criticism of Japanese military action. IOC members, however, grew increasingly concerned about the viability of the Tokyo Games, especially after the British Olympic Committee announced a movement to boycott.

Ultimately, it was this confluence of issues—war, austerity, nationalism, and international opposition—that caused Tokyo, and in reality, Japan, to withdraw its offer to host the games and forfeit the 1940 Tokyo Summer Olympics (and the 1940 Sapporo Winter Olympics). On July 15, 1938, the Japanese Cabinet—not the OOC or Tokyo municipal government—voted to forfeit the Olympics. The next day, Japanese IOC members telegraphed the IOC to inform them that they were forfeiting the 1940 Olympics but intended to apply to host the 1944 games. The IOC quickly awarded the 1940 Olympics to Helsinki, although those games too would be canceled due to the war in Europe. Japanese dreams that the “China Incident” would be rapidly resolved were as illusionary as their dreams of hosting the 1944 Olympics, also canceled due to World War II.

It was this confluence of issues that caused Japan to withdraw its offer to host the games.

Following the war, the Japanese were bitterly disappointed to find themselves excluded from the 1948 Olympics. When the Occupation of Japan ended in March 1952, Tokyo immediately bid again to host the Olympics, arguing that it would provide a chance for the world to see a new and peaceful Japan. This echoed the internationalist arguments for 1940. It also shows how important it was for Tokyo and Japanese officials associated with the Olympic movement to regain a treasured honor that had been forfeited due to wartime, ideological, and political pressures.

The “Phantom Olympics” were discussed by Tokyo officials and the OOC as an unfortunate set of circumstances or implied that Tokyo was owed another chance, which it received when it hosted the 1964 Tokyo Summer Olympics to great fanfare. It is hard to imagine that the specter of 1940 and potentially twice being the host of a canceled or forfeit Olympics wasn’t haunting the minds of the organizers and politicians as they’ve pressed forward with 2021 in the face of strong public resistance.

This article was originally published in Historians.

Articles you may also be interested in

Australia’s first action in the Pacific in World War II a valiant catastrophe

Just before midnight on 7 December 1941, Flying Officer Peter Gibbes stepped off the train at Kota Bharu on the coast of northeast Malaya after a long, tiring journey up the peninsula from Singapore. Gibbes, an airline pilot in peacetime, had been newly posted to the Royal Australian Air Force’s 1 Squadron, which in the […]

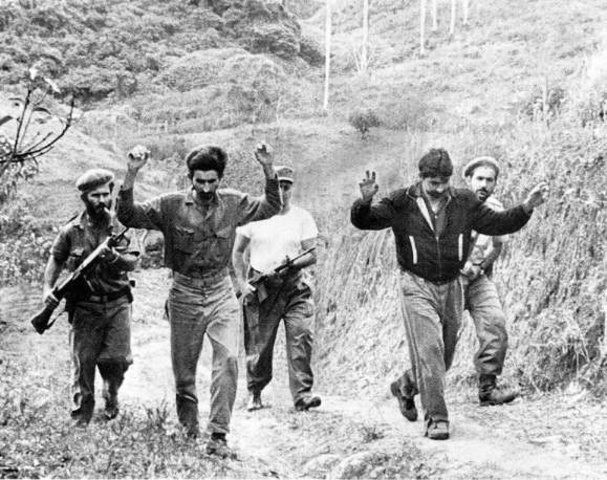

Hubris and Miscalculation: The failure of the Bay of Pigs invasion

HUBRIS AND MISCALCULATION: THE FAILURE OF THE BAY OF PIGS INVASION By Michael Vecchio The threat of Nazi villainy had been defeated, however another authoritarian threat rapidly placed over half of Europe behind what Winston Churchill called an “Iron Curtain”. The Soviet Union’s aggressive brand of Communism startled much of the Western world, but perhaps […]