Reading time: 6 minutes

The image of “The Viking” has always been a colourful one in the minds of society, with fear-inducing images conjured of blonde-haired, blue-eyed barbarians, and pillaging and plundering their way through Europe on a history-changing quest to conquer. This almost mythical collective interpretation of horned helmets and terrifying ships is certainly a popular one. However, recent explorations have brought to light new insights to shift these perceptions, altering the history books and allowing us to look with better clarity at the era between 750 CE and 1050 CE.

A turning point in historical understanding took place in 2020, when new findings published by Nature challenged our long-standing collective image of what being “A Viking” truly meant. In a six-year undertaking by experts from the University of Cambridge and the University of Copenhagen, a large-scale DNA sequencing effort took place across Europe, yielding results that not only answered questions raised by historians, but also offered new insights, and prospective areas for further study.

By Madeleine Lily

As part of this research, the specialist teams gathered remains from various Viking burial sites across Europe. Notably, not just Scandinavia, but many places beyond in which Viking activities had been pinpointed. From these endeavours, a total of 442 Viking Age genomes were gathered and tested, including samples from men, women, children and babies. Using new technologies DNA was gathered from the teeth and petrous bones from these remains, and the findings have been illuminating.

Perhaps the key takeaway from this research was the revelation that Vikings were a more diverse group than initially thought. For the first time, DNA evidence has been able to establish what the warriors looked like, with many having black or brown hair, from foreign-originating genetic influences dating even further back than before the Viking age itself. Out with the perception of those blonde-haired, blue-eyed soldiers, and in with the idea of medieval diversity, with DNA stretching as far as southern Europe and Asia, as reported by the University of Cambridge.

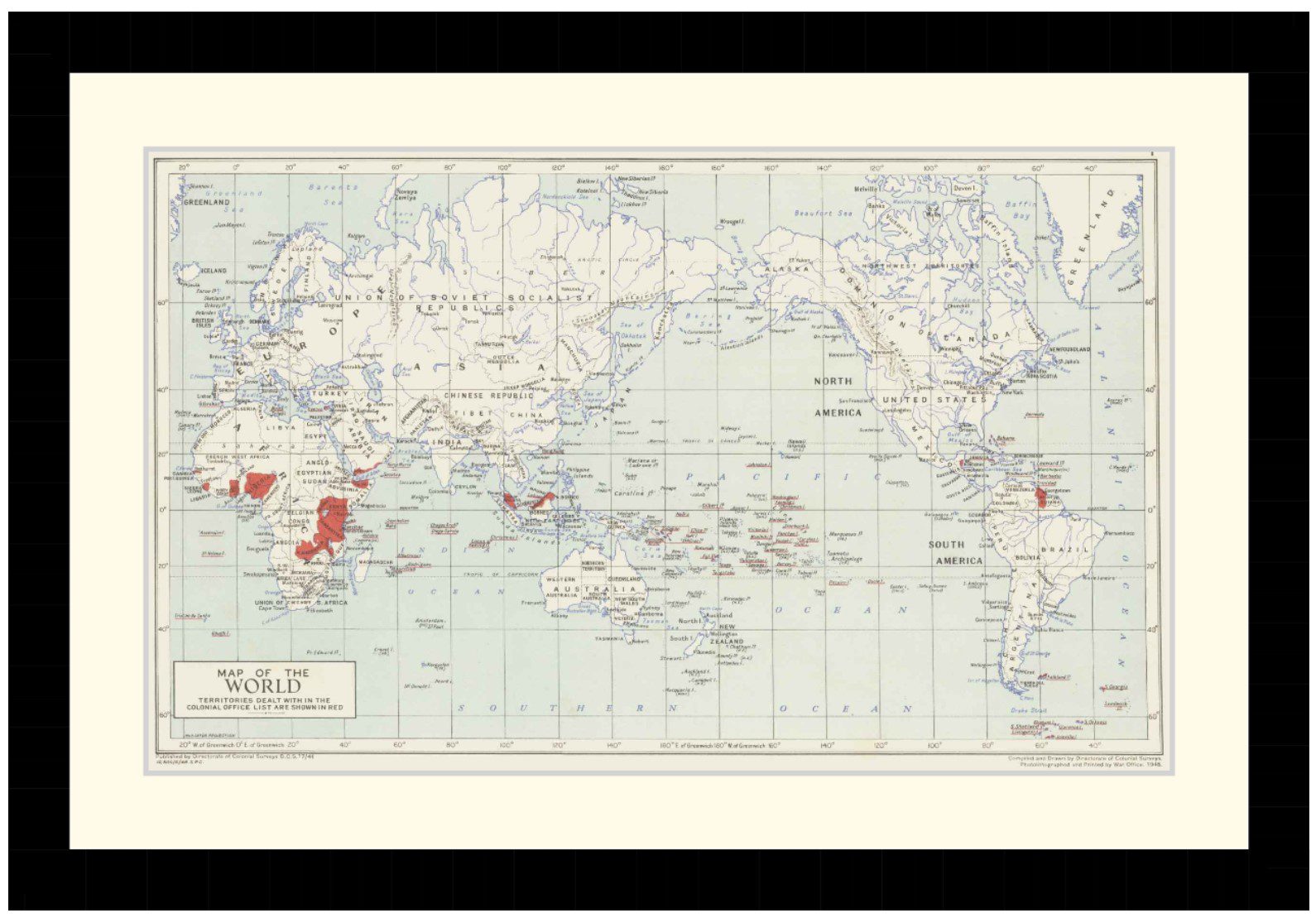

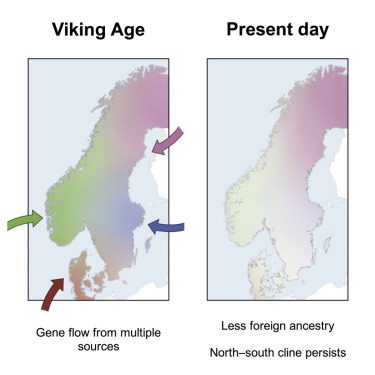

So, how did this gene diversity come to be? Well, the answer lies in migration. Established as a key part of Viking study, we’ve all seen the maps of Europe embedded in each history book, often with arrows radiating from the north across their neighbouring countries: a trajectory of settlements and the culture, genetics, language, and lifestyles they carried along the way. Now, thanks to this recent study into gene flow throughout Viking age Europe, a clearer picture has emerged as to where these voyages took place.

From the DNA results, specialists were able to confirm that Viking parties from the different areas of Scandinavia each chose separate areas of Europe to migrate to. Specifically, the patterns followed Vikings from Denmark heading to England; Norwegians into Ireland, Iceland, and Greenland; and those from what is now Sweden towards the Baltic regions. Before the proper analysis of evidence, these trajectories had not been confirmed.

However, the movement doesn’t stop there. Most intriguingly, ancestry was traced from other European countries back into Scandinavia itself during the Viking period. For instance, data from this study published by Cell indicate gene flow heading from the British-Irish Isles back into Scandinavia both during and before the Viking era, as well as from further afield. This discovery is explored in interesting detail by History Guild here, and it goes to show that the blending of cultures was largely due to not only migration, but also because of trading and other interactions which took place on Baltic shores.

Fascinatingly, these same studies have also revealed that these high levels of non-local ancestry found among Viking-era Scandinavians does not correlate with those of later ages. In fact, more people may have Viking heritage than previously realised, thanks to the diversity recently evidenced.

Moving back towards the exploration of what it meant to be a “Viking,” these studies have also raised elements to challenge our perceptions even more. While it is true that the concept of a “Viking” is rooted in Scandinavian culture, as explored by Science, it may be more appropriate to view the term as a role, rather than a matter of heredity.

For instance, the discovery of non-genetically Viking male remains in Orkney, Scotland was surprising, considering they were resting in a traditional Viking burial site with various memorabilia related to the period. The Cambridge study discovered groups such as the Picts operating in Viking ways, without any genetic crossover. It was not uncommon for warriors from across the continent to adopt Viking ways, making the term more of a social identity or lifestyle. For some, it was a family matter, evidenced by the notable discovery of four Viking brothers buried together in an Estonian cemetery having perished on the same day, as part of the same raid.

In many ways, this moving link offers more of a familiar insight, rendering the Vikings in a more human image in our collective imagination. Perhaps, in further challenge to pre-existing perceptions, there’s beauty to be found here too. For instance, a research project undertaken by The National Museum in Copenhagen dated glass fragments to between 800 to 1100, placing dazzling and unique glass windows in Sweden, Denmark, Norway and northern Germany during the Viking era. As discussed in The Archaeologist, this quashed stereotypes of barbarity, bringing culture and artistry into their story.

Looking forward to the future of Viking Age study, it’s hard to predict what other revelations may come to light. This 2020 DNA study may have answered some historical disputes, however there are still further questions that remain unanswered. In 2021, evidence reported by Nature placed Viking presence in the Americas in 1021, almost 500 years before Christopher Columbus arrived. Further exploration of this migration, along with debates regarding colonisation to the east, still lie ahead.

In conclusion, allow us to consider what the word “Viking” actually means. Defined by Britannica, the term comes from the Old Norse word “víkingr,” meaning “pirate, raider.” One wouldn’t limit the notion of a “pirate” or a “raider” to a specific nationality or region, but instead to a lifestyle, or a job description. It’s funny, because through the years the notion of “The Viking” has been considered a term of race, a heredity, a collective term for horn-helmeted barbarians, who pillaged and plundered their way out of Scandinavia into the unsuspecting remainder of Europe. Now, thanks to recent discoveries and technological advancements, our perceptions have been challenged, resulting in a clearer understanding that perhaps the term “Viking” would be better interpreted in a way its etymology has suggested all along.

Podcast episodes about Viking migrations

Articles you may also like

Ruin Ridge – Podcast

During the 1st Battle of El Alamein the 9th Australian Division was tasked with the capture of Ruin Ridge. Despite heavy fighting during the opening stages they achieved some of their objectives, but their successes obliged General Rommel to divert large numbers of troops to contain the Australian advance. The fighting then became desperate, leading to heavy casualties and the near decimation of one battalion.

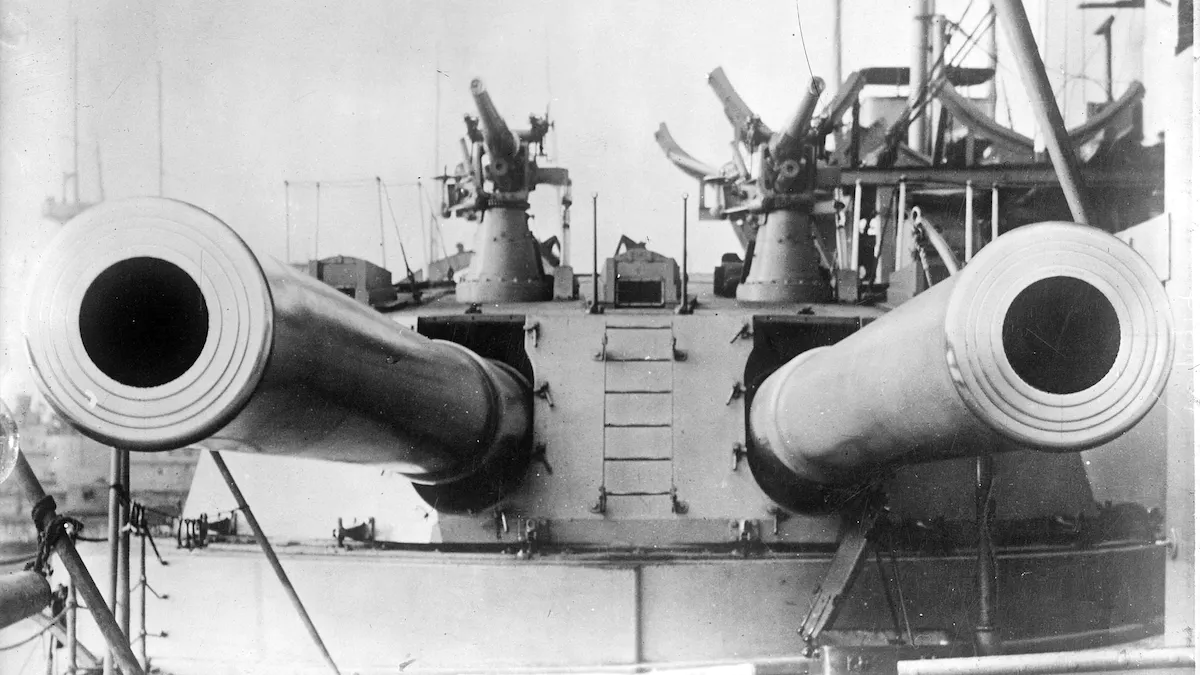

Maths swayed the Battle of Jutland – and helped Britain keep control of the seas

Reading time: 5 minutes

If you’re about to fight a battle, would you rather have a larger fleet, or a smaller but more advanced one? One hundred years ago, on May 31 1916, the British Royal Navy was about to find out if its choice of a larger fleet was the correct one. At the Battle of Jutland – as the major naval battle of World War I is known in English – these choices were unusually influenced by mathematics.

General History Quiz 213

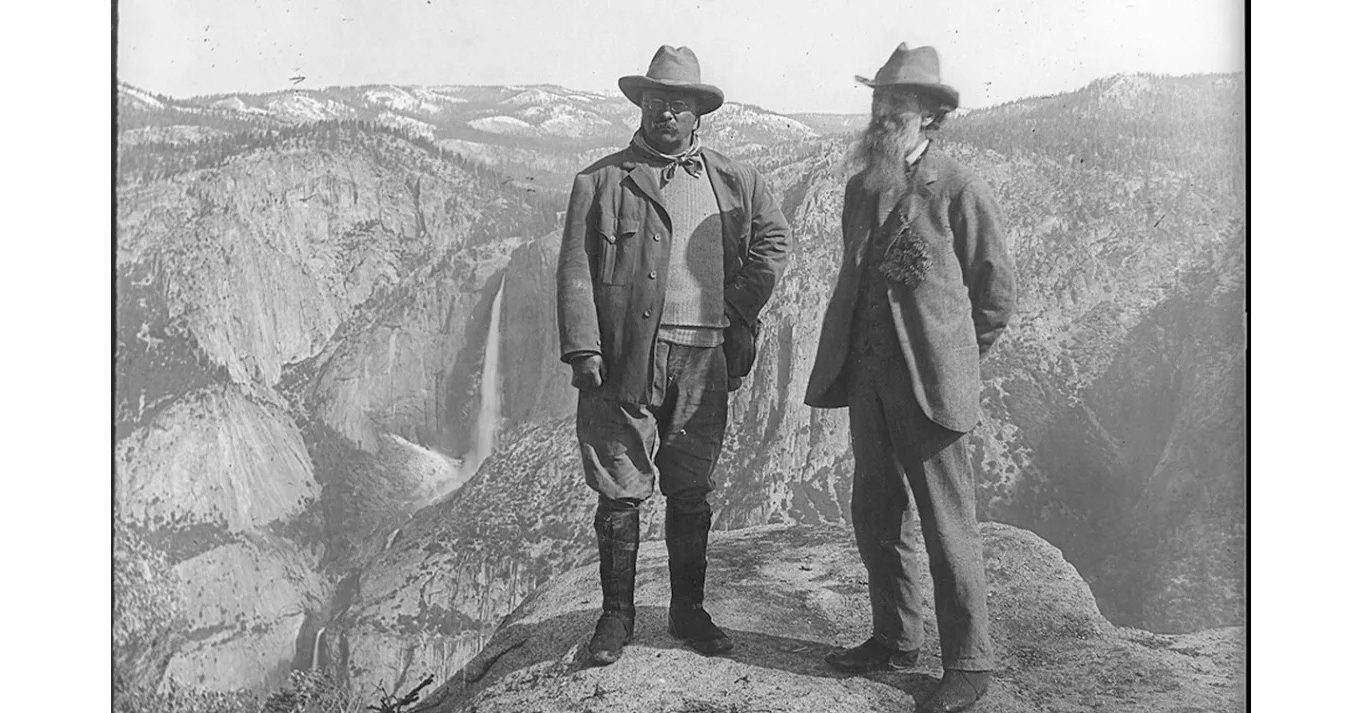

1. What was the relationship between Theodore Roosevelt and Franklin D. Roosevelt?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.