Reading time: 7 minutes

A browse through any military history book will no doubt bring up titles of famous officers, often bearing unusual, surprising, or sometimes downright hilarious nicknames. In many cases, it’s clear where the sobriquet originated, while other examples hold a less-obvious significance.

By Madeleine Lily.

However, a study into the topic highlights a trend emerging from these nicknames, with many bearing elements of respect or admiration hidden behind each amusing adjective. Here are some of the greatest examples of historical nicknames, including how each notable figure came to inherit such unique monikers.

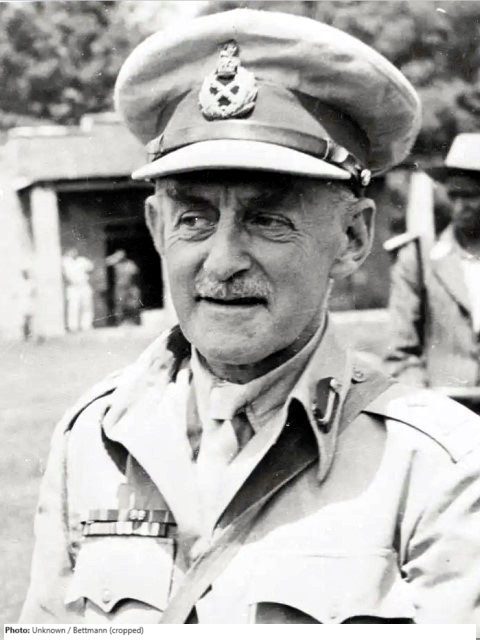

To start, we consider Major General Robert “Looney” Hinde (1900-1981), who was given that nickname as a nod to his unique personality. A courageous Scottish officer, Hinde was noted for his involvement in “madcap pranks”. His daughter fondly remembered a story about him that she told the Scottish Daily Mail. During the 1944 Battle of Villers-Bocage he stumbled upon a rare caterpillar. Hinde paused to study it and excitedly asked his headquarters staff ‘anyone got a matchbox?’. When a subordinate suggested that they had more important tasks to attend to, Hinde exclaimed, ‘Don’t be such a bloody fool… you can fight a battle every day of your life, but you might not see a caterpillar like that in 15 years.’

His eccentricity also played in his favour, in 1947 he was detained by a Russian patrol while wandering along the border of the British and Soviet sectors of Berlin with a pair of binoculars. After explaining that he was simply birdwatching he was released with an apology.

It’s interesting, that while “Looney” may strike some as a rather disrespectful choice of adjective to use, it would appear the moniker was issued with only kindness and fond affection – a sentiment which appears to transpire throughout many examples of military bynames.

Nicknames held by contentious figures throughout history often carry additional heft, which is why names such as “Old Blood and Guts” can be construed in as many different ways as its holder himself. US World War II General George Smith Patton (1885-1945) was quoted by the St. Louis Post Dispatch in accepting this gory title: “that’s all right; it serves its purpose.”

While conjuring graphic images of war itself, this nickname perhaps calls to light the tenacity with which Patton led during his command of both the US 7th Army and the US 3rd Army through France post-D-Day. However, while effective, it’s fair to conclude that not everyone agreed with his methods, and controversies surrounding the general continued even after his death.

A nickname not too dissimilar to Patton’s was held by Australian General George Alan Vasey (1895-1945,) who was referred to as “Bloody Vasey” by his men. However, it was less Vasey’s leadership style which earned him this nickname, more his colourful language of choice.

A story from the Battle of Greece describes this perfectly through a quote from Vasey:

Here you bloody well are and here you bloody well stay. And if any bloody German gets between your post and the next, turn your bloody bren around and shoot him up the arse.

Brigadier George Vasey, commander of the 19th Brigade at the Thermopylae line.

Both these “Bloody” examples show how officers receive their nicknames, they’re directly bestowed upon them by their soldiers themselves. While this does show a level of familiarity between an officer and his troops that is concerning to some militaries, it shows that both Patton and Vasey spoke the language of their soldiers.

Another commander whose colourful choice of vocabulary gave him his nickname was Brigadier General Frank ‘Howlin’ Mad’ Howley (1903-1993). He was particularly noted for the screaming matches he engaged in against the Soviets when he was responsible for the American occupation zone of Berlin.

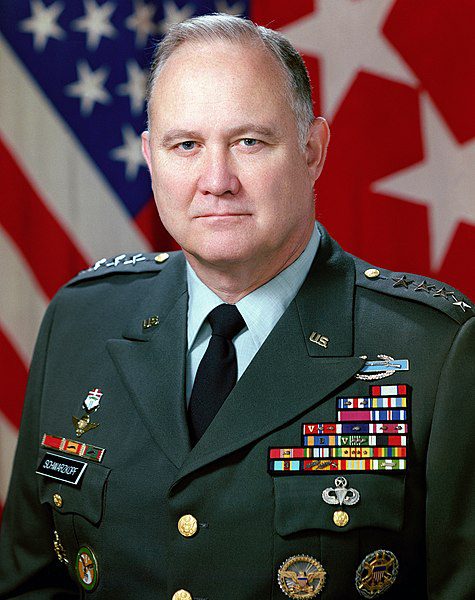

General Herbert Norman Schwarzkopf Jr. (1934-2012). An officer with a powerful temper who accepted no compromise, Schwarzkopf agreeably took on the nickname “The Bear.” However, it was perhaps the rhythmic punch of his second nickname, “Stormin’ Norman,” which lives on most famously.

Nicknames have also been seen to travel across opposing sides in war. The German field marshal Erwin Rommel (1891-1944) had the nickname “der Wüstenfuchs” (or “Desert Fox,”) owing to his stealthy surprise attacks in the field. While this nickname was bestowed upon Rommel by his troops, the English adopted the same name for him in their own camps. Considering that nicknames are often derived from either fear or affection, it’s interesting to consider that a degree of respect was involved in this nickname becoming more widespread.

British Lieutenant-General William Gott (1897-1942) also earned himself a nickname inspired by his German foes. “Strafer Gott” was a play on the slogan “Gott strafe England” (“God punish English”) used by Germany in World War I, so the use of this stolen enemy nomenclature almost appears to be an act of reappropriation by the English side.

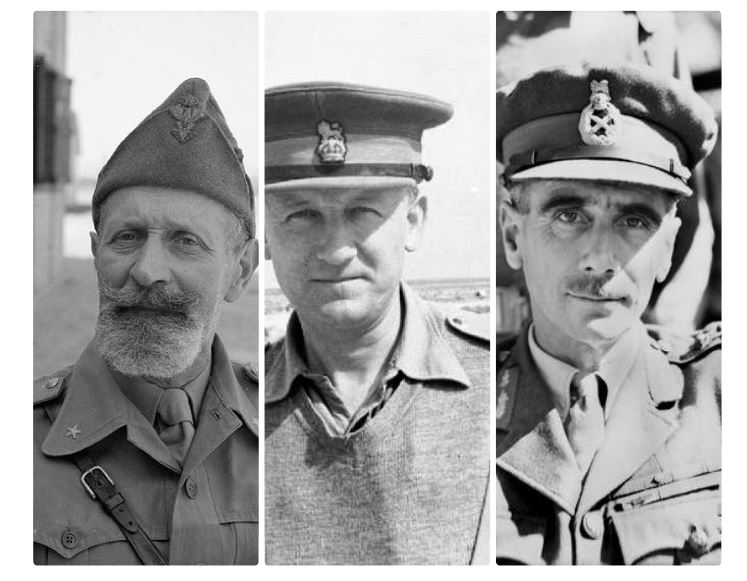

Perhaps the most basic nicknames are those that were born from the physical features of their bearer. Italian Lieutenant General Annibale Bergonzoli (1884-1973) was known as “barba elettrica” (“Electric Whiskers”) thanks to his striking beard, while Australian Major General Arthur Allen (1894-1959) went by “Tubby” due to his build, similarly to Field Marshal Henry ‘Jumbo’ Wilson (1881-1964). Another prime example would be the 1st Duke of Wellington Arthur Wellesley (1769-1852), who was affectionately referred to as “Old Nosey,” in reference to a particular protruding facial feature.

Unsurprisingly, “Old Nosey” was not the only nickname held by Wellington during his command. Many reports will tell you that “The Iron Duke” was another powerful choice. One might assume this name references his unwavering rule or power, perhaps? Maybe not. According to the Wellington Collection, it was less his personality which gained him the name, more instead the fact that he installed iron bars on his Apsley House residence to prevent mob attacks during his service as Prime Minister.

Of course, when we think of “Iron” Prime Ministers of Great Britain, “The Iron Lady” Margaret Thatcher (1925-2013) also comes to mind. However, it was notably her unwavering politics and leadership which earned her this name, rather than her use of the metal within her household.

So, the element that unites all of these examples is that the military nicknames were, in most cases, bestowed upon the bearers by their soldiers. Of course, not every commander is awarded a nickname, thus reflecting a degree of either affection, or even perhaps revulsion felt towards them. Anyone in-between would not warrant a nickname.

Podcasts about Military Nicknames

Articles you may also like

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.