Dispatches from Red Square: reporting Russia’s revolutions then and now

Reading time: 9 minutes

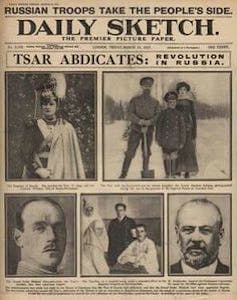

“No news from Petrograd yesterday”, was the headline in the Daily Mail on March 14, 1917. The story – or non-story – which followed, was only a few dozen words: “Up to a late hour last night the Russian official report, which for many months has come to hand early, had not been received”, it ran. So why publish it? The non-appearance of the daily news bulletin from the Russian government had led the Mail’s writer, trying to prepare a report in London, to suspect something was going on.

It was.

During the silence, the last tsar, Nicholas II, had abdicated and centuries of autocracy had come to an end in Russia. Correspondents in Petrograd were only able to tell their stories later. Russia’s links to the world were cut off. Donald Thompson, a pioneering news cameraman from the United States, later related his experience at the telegraph office: “The old lady in charge … told me not to waste my money – that nothing was allowed to go out.”

By James Rodgers, City, University of London

Despite the difficulties they faced, at the end of the Soviet era – as at its dawn – journalists, both international and Russian, shaped the world’s understanding of the events that would influence the rest of the century. My current research, prompted both by my former career as a correspondent in Russia and my academic interest in the history of journalism, involves the study of archive material from Russia’s revolutionary years.

On August 19 1991 – 25 years ago this month – a group of senior Soviet officials declared that they had taken power. The coup leaders said that the then leader of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), Mikhail Gorbachev, was unable to carry out his duties on the grounds of ill health. In fact, they were dismayed at the direction his policies were taking and sought to stop them. Gorbachev was trying to save the Soviet system by reforming it. The conspirators saw his policies as a betrayal of Marxist-Leninist principles.

The coup was unconvincing from the start, even if troops did obey instructions to position themselves at important locations. The headquarters of TASS News agency was one of them. The coup leaders understood very well that they needed to control the media in order to convince the country, and the world, that they had succeeded, and were serious.

Read More: FOUR DAYS IN AUGUST: THE SOVIET UNION’S FINAL BLOW

Swan Lake and circuses

Despite the fact that the media were much more easy to control a quarter of a century ago – especially in a totalitarian state, albeit one which had seen considerable liberalisation – the plotters did not do this well. Screening Swan Lake on the main television channel was fine as far as it went. Continuous TV news was still a novel concept outside the United States and the Soviet Union never experimented with a version of CNN.

In any case, the coup leaders could not have counted on the support of the news media. The “glasnost” (openness) policies of the “perestroika” (restructuring) period, as Gorbachev’s reforms had been called, had been kind to journalists. Newspapers, radio, and television were able to report on, and discuss, issues which had previously been forbidden. Gorbachev had understood that he needed the enthusiastic backing of the media to mobilise his reforms. He gained their support by giving them unprecedented freedom.

Something similar was true for Western media. There were still travel restrictions, like not leaving the Moscow region without permission. Generally, however, there were unprecedented opportunities for news-gathering.

There were new ones for distribution, too. That summer I was working for Visnews (soon after to become Reuters Television). The agency had been given the ability to send material to London from its Moscow bureau, rather than from Soviet TV headquarters. The link ran through Soviet TV, but material sent that way was not censored, however negative. I do, though, remember a phone line going dead once when, during a conversation with a friend in London, I expressed the view that life for ordinary Muscovites was hard.

Crucially, as the coup of August 1991 continued and eventually crumbled, journalists in the Soviet capital retained contact with the outside world. Among the material they sent was footage of a press conference for the international news media. The sight of the supposed new leader of the Soviet Union, Gennady Yanayev, trembling apparently from nerves, the effects of strong drink, or both was so enduring that it was remembered in his obituaries almost two decades later.

The other image from those days was that of Russia’s first elected leader, Boris Yeltsin – then the president of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR) – standing on a tank to defy the coup leaders. However future generations will judge him, Yeltsin made his mark on Russian history by making sure the country would not return to Marxism-Leninism. This was a key moment in that process – the picture appeared across the world. Yeltsin presumably knew how it looked, coming – as he did – from a Russian political tradition that had become good at making its leaders appear in a favourable light.

Back in 1917, the Bolsheviks would probably have found a way to hold on to power – but the much diluted version of totalitarianism which clung on in 1991 could not. On the eve of the Soviet era the media had been easier to control – during the revolutionary year of 1917, shutting down the telegraph link between Petrograd and the rest of the world was sufficient to shut down news – as the Daily Mail headline demonstrated.

Interested observers

So, different though the beginning and end of Soviet power were, they had some features in common. First, they fascinated the West. At one level, the reason is obvious: self interest. When revolution rocked Russia during World War I, its allies were deeply concerned that unrest would mean the Russian Army no longer wanted to fight. The Reuters correspondent in the Russian capital knew this:

The first duty of a British correspondent in these days of national upheaval is to assure his compatriots that ‘Russia is all right’ as a friend, ally, and fighter. The very trials she is undergoing will only steel her heart and arms.

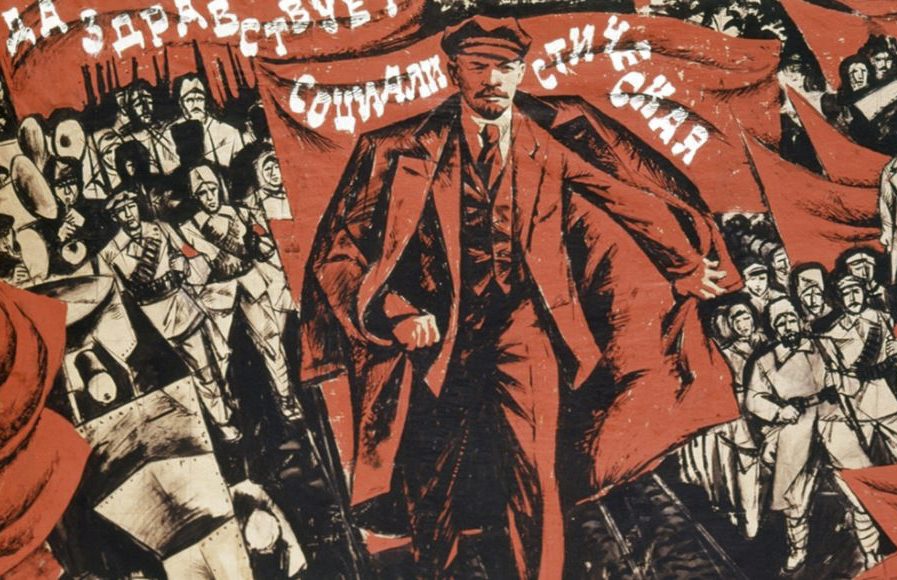

The optimistic message which ran in British newspapers following the initial upheaval proved to be ill-founded. Later that year, Lenin would seize power with a promise of “peace, land and bread” and by 1918, Russia was out of the war with Germany and on its way to war with itself.

In 1991, the hope was that Russia no longer wanted to fight: not a Cold War, at least. That proved to be the case. Now, though, some argue, given confrontation over Ukraine and Syria, this ceased to be the case some time ago.

The second level of the West’s fascination transcends self interest. For much of its history, Russia has been seen as a mysterious, sometimes menacing, presence at the edge of Europe. For all it has influenced European and world history, relatively few outsiders ever visit.

Apart from diplomats, whose job it is to observe, and interpret – but always represent the interests of their country – journalists are the main conduit through which we have come to know about Russia.

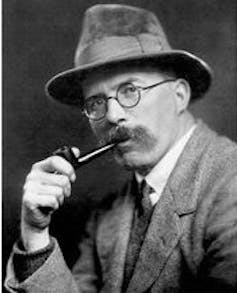

Journalists may have less responsibility, but have more insight. In 1917, Arthur Ransome – more famous today as the author of children’s books – and his contemporary Morgan Philips Price, are two whose reporting is still well worth reading today. That is not because it was perfect, but because it had an understanding which was often lacking elsewhere.

Both understood that Bolshevism was there to stay. Their judgement may have been influenced by personal and professional loyalties – Ransome was very well connected within the new hierarchy (he married Trotsky’s secretary).

Philips Price, meanwhile, furious at the censorship which gagged his reporting, wrote a pamphlet which the Bolsheviks were happy to circulate to promote their cause – Philips Price was “held to be liable for treasonable activities and aiding the ‘King’s enemies’”. In the event he was never charged with treason but his work was censored. Whatever their motives, both Ransome and Philips Price challenged the conventional wisdom – this being at the time that Lenin’s regime would soon crumble – and by doing so got the story right.

Ignore at your peril

Something similar happened with Western perceptions of Russia when the Soviet regime finally did fall apart in 1991. Perhaps relieved that the Cold War was over, the West failed fully to understand the humiliation which Russia felt. The last British ambassador to the USSR, Sir Rodric Braithwaite, explained at Chatham House in 2011:

We keep on failing to understand the nature of the trauma that hit all Russians in 1991. At the end of 1991, Russians were starving; the other superpower, they were starving, and I mean that literally, and we were giving them food aid.

That humiliation eventually had political consequences. The current Russian president, Vladimir Putin, has built his popularity on his image as a tough leader unwilling to do the West’s bidding. Both at the beginning, and the end, of the Soviet period, Russia headed in directions the West did not expect and came not to welcome.

As long as Russia remains both remote and relevant, informed and thoughtful reporting will be a vital part of our understanding – “dutiful British correspondents”, “King’s enemies” and all.

This article was originally published in The Conversation

Articles you may also be interested in

The wild decade: how the 1990s laid the foundations for Vladimir Putin’s Russia

Reading time: 6 minutes

By securing victory in a national vote on constitutional changes, Vladimir Putin could now remain president of Russia until 2036 if he chooses to stand again. After 20 years in power, the narrative of Russia’s chaotic 1990s remains core to Putin’s legitimacy as the leader who restored stability.

The Russian Revolution

For most people, the term “Russian Revolution” conjures up a popular set of images: demonstrations in Petrograd’s cold February of 1917, greatcoated men in the Petrograd Soviet, Vladimir Lenin addressing the crowds in front of the Finland station, demonstrators dispersed during the July days and the storming of the Winter Palace in October. What happened in the Russian Revolution? These […]

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.