Reading time: 5 minutes

The Rosetta Stone laid the groundwork for our understanding of Ancient Egyptian language and culture when French scholar Jean-François Champollion cracked its code in September 1822. But the Rosetta Stone isn’t the only unsolved puzzle out there. Since the discovery of the Indus Valley Civilisation in the 1920s, the Indus Valley Script has remained an enigma, resisting all attempts at decipherment. From the origins of the civilisation to the reasons why the script remains undecoded, and what the future may hold, unlocking the Indus Valley Script could reveal important insights into one of history’s great ancient cultures.

By Nina Colleen Sumner

Exploring the Indus Valley Civilisation

The Indus Valley Civilisation (also known as IVC or the Harappan Civilisation) is described as a Bronze Age civilisation that lasted from 3300 BCE to 1300 BCE. The IVC existed in the northwestern regions of South Asia, extending from what is modern day northeast Afghanistan to Pakistan and northwest India. The Indus civilisation’s settlements spanned an area greater than that of Ancient Egypt at its peak. Indus jewellery examples have been found as far as Mesopotamia (around 1,500 miles away), highlighting its connection to the wider world through trade.

The Indus cities were sophisticated for the time, being built on a grid pattern with drains that carried sewage from homes emptying outside the city walls. While this demonstrates the significance of the Indus civilisation, there are still mysteries being discovered — and many left to uncover. Over time, scientists have continued to unlock the secrets of the Indus Valley Civilisation, human bones found by archaeologists have been the subject of two new studies, in which researchers “have found intriguing clues to the makeup of one city’s population.” For example, bones have revealed that many of the deceased found in a Harappan cemetery are from people who grew up outside of the city, revealing significant immigration to the city.

Dissecting the challenges involved

Not much is known regarding the language (or languages) of the Indus Valley Civilisation. The language of the IVC is referred to as the Harappan language, though the language is officially considered ‘unknown.’ As a result, the language is unclassified, though it’s possible that it could belong to the Dravidian language family. This, however, is only a slice of the theories and hypotheses out there. Bahata Ansumali Mukhopadhyay, an independent researcher who has analysed historical evidence regarding language. Mukhopadhyay went on to find that words used for ‘elephant’ in the Bronze Age Mesopotamia were borrowed from ‘pilu,’ a Proto-Dravidian word for elephant — this is noted to be “prevalent in the Indus Valley Civilisation.” Mukhopadhyay’s research, published in Nature Humanities and Social Sciences Communications “indicates the possibility of Proto-Dravidian speakers migrating from Indus valley to South India,”.

The Indus script was mainly written with signs that could symbolically convey meanings to people of different dialects, and languages, across Indus settlements. Over one hundred attempts have been made by scholars across different fields to try and decode the Indus script, all without success. There are a number of theories surrounding the language, potentially linking it to Sanskrit, Dravidian, Mesopotamian, or even Egyptian. However, it’s also pointed out that the script may not be in any one language, either, further complicating its already puzzling nature.

There are many challenges and various theories involved in trying to decipher the Indus Valley Script. Some researchers argue that the inscriptions weren’t even “true writing,” but perhaps something more of “an alternate symbolic system similar to emblems,” which may convey more generalised meanings. The Indus inscriptions themselves range from symbols that resemble animals (such as bulls or elephants) to simpler markings such as lines. When considering all of the characters that have been found, it’s explained that researchers have compiled between 400 and 700 distinct signs. Most inscriptions are rather brief, composed of an average of just four or five signs, the longest example, on the other hand, contains 30 characters.

An ongoing project

What’s also important to remember is that along with expert guidance, modern technology could also play a big role in making new breakthroughs. Better databases of texts and new computational methods for finding patterns among the script bring to light technology that may help to one day crack the code — or at least make some progress. In 2019 MIT researchers developed an algorithm “informed by patterns in how languages change over time.” The idea is to align words from a lost language in order to match their counterparts in a language that is already known, effectively ‘translating’ what may be possible to understand. The technology was tested on a language that took epigraphists nearly six decades to decipher (the language is known as Linear B, or the earliest form of Greek), in order to see if the technology could do what humans did but faster — ultimately producing results with “remarkable accuracy.” While technology highlights a future for the decipherment of the Indus script, it’s essential to realise that human research is still imperative to decoding the enigma.

The Indus Valley Civilisation is remarkable for a civilisation that existed over 4,000 years ago. There are still a great many aspects of this civilisation that are unknown. However with luck, diligent research and the application of new technology we can hope that the Indus Valley Script will be deciphered soon.

Articles you may also like

The History of Gunpowder: From Elixir of Life to the Revolution of Warfare

Reading time: 6 minutes

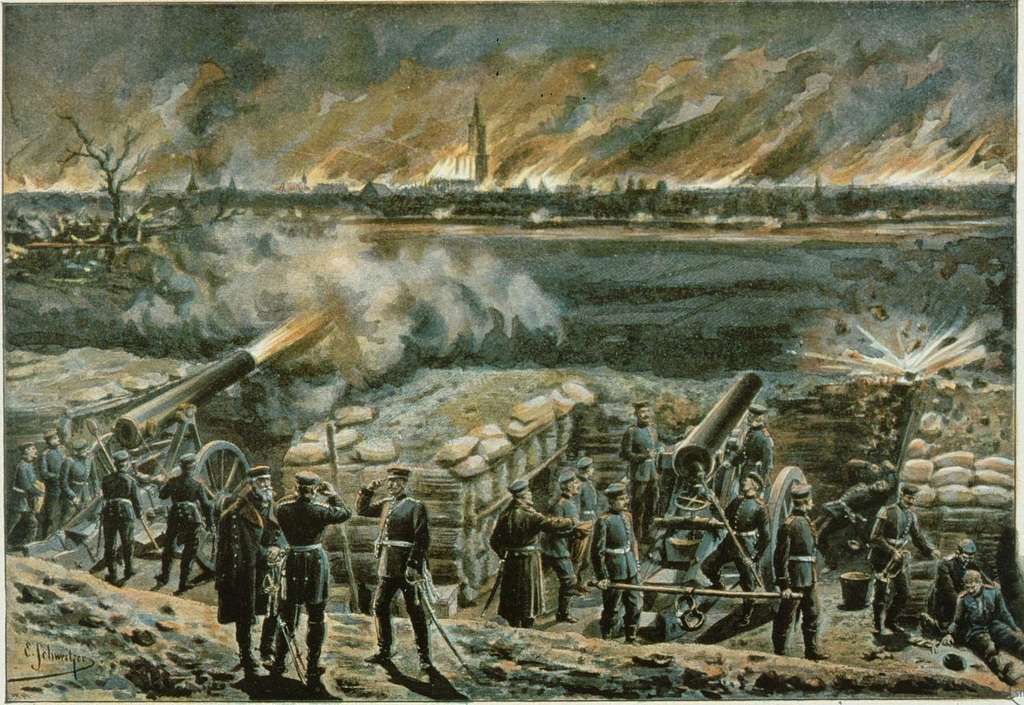

One of the most famous materials in history, gunpowder is largely responsible for European dominance in the 20th Century, the fall of Constantinople’s impregnable walls, and much more.

Yet this devasting and destructive powder did not materialise into rifles and cannons in Europe in the 14th and 15th Centuries. Rather, it was discovered initially in China, several hundred years prior, by alchemists searching for, ironically, the elixir of life.

So how did gunpowder go from a powder for immortality in 9th Century China, to the fiery fuel of guns in Europe and the Middle East over 500 years later?

Remembering Sachsenhausen-Oranienburg

REMEMBERING SACHSENHAUSEN-ORANIENBURG By Rachel Horne. 35 kilometres north of Berlin, you will find the Nazi concentration camp of Sachsenhausen-Oranienburg. Some particularly well-known figures were imprisoned here, including the Prime Ministers of Spain and France, and the wife and children of the crown prince of Bavaria. Joseph Stalin’s oldest son was also interred at Sachsenhausen, before […]

Maths swayed the Battle of Jutland – and helped Britain keep control of the seas

Reading time: 5 minutes

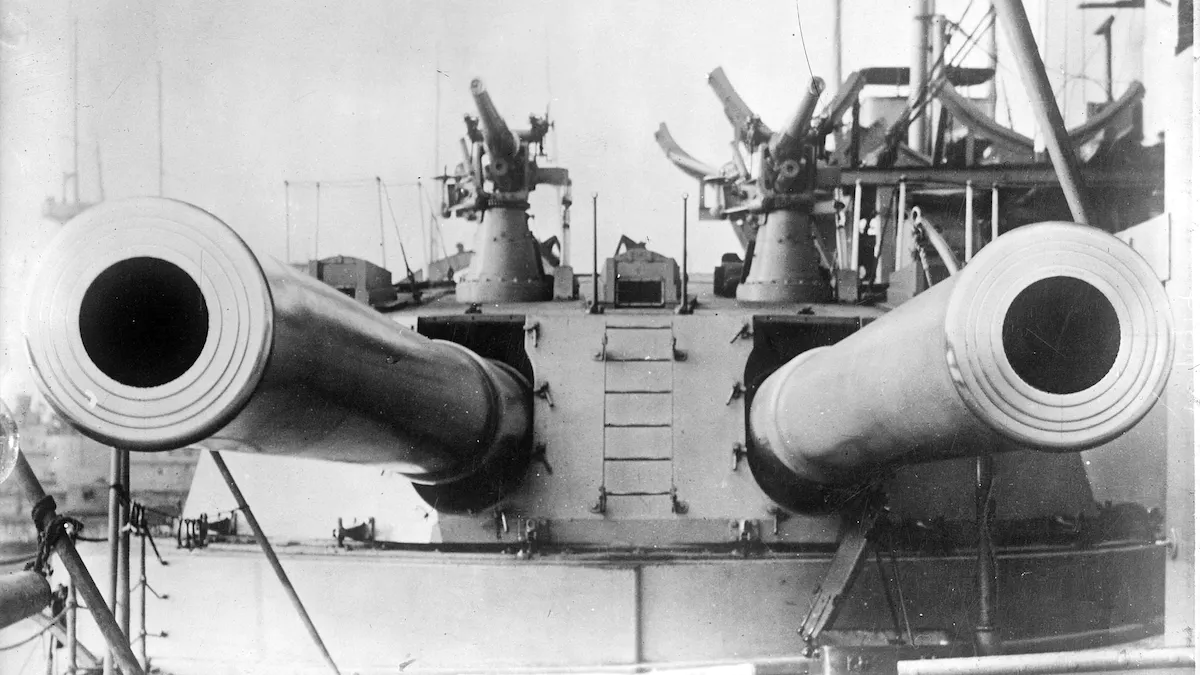

If you’re about to fight a battle, would you rather have a larger fleet, or a smaller but more advanced one? One hundred years ago, on May 31 1916, the British Royal Navy was about to find out if its choice of a larger fleet was the correct one. At the Battle of Jutland – as the major naval battle of World War I is known in English – these choices were unusually influenced by mathematics.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.