Reading time: 6 minutes

Is cheating at the Olympic Games a symptom of modernity? Do recent scandals involving athletes signal the decline of the Olympic idea?

While in antiquity instances of bribery remained the exception – and were heavily punished – there’s plenty of evidence to suggest that attempts to manipulate the outcome of the competitions are as old as the Games themselves.

By Julia Kindt, University of Sydney

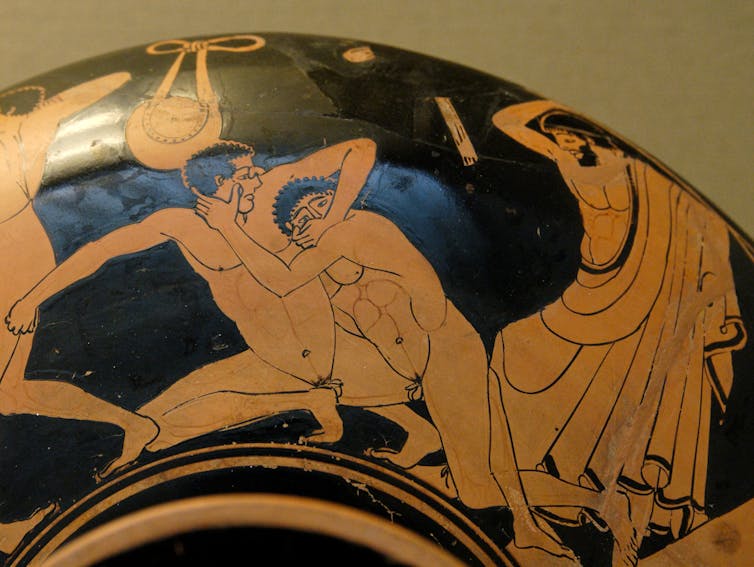

Take the example of Damonikos of Elis. One father of a young and promising athlete bribed the father of his son’s opponent to ensure his offspring a victory in wrestling. Both fathers were found out and fined.

Or consider the case of the Athenian Kallipos, who bribed his opponents to secure victory in the pentathlon. He, too, was caught out and a heavy fine was imposed on him and on those who had accepted the bribe.

Athens, however, refused to pay and even boycotted the Games. It took the intervention of the Delphic Oracle to resolve the situation: Delphi announced that no more oracles would be delivered to the Athenians until the they had paid up.

Such attempts to influence the outcome of the Games confirm that the competitive streak ran strongly through ancient Greek culture. In a world where few believed in an afterlife, this-worldly glory mattered immensely. And what better opportunity to show off than competing with others before an audience from all over the Greek world?

From 776BCE on, the Greeks gathered every four years to celebrate the Olympic Games and compete in a number of disciplines, including the foot race, boxing and various equestrian skills. The Games became part of an elaborate festival circuit, which also featured competitions in trumpet-playing and the recitation of poetry. Even beauty contests – for men! – are attested, albeit not at Olympia itself.

Scandal in the sanctuary

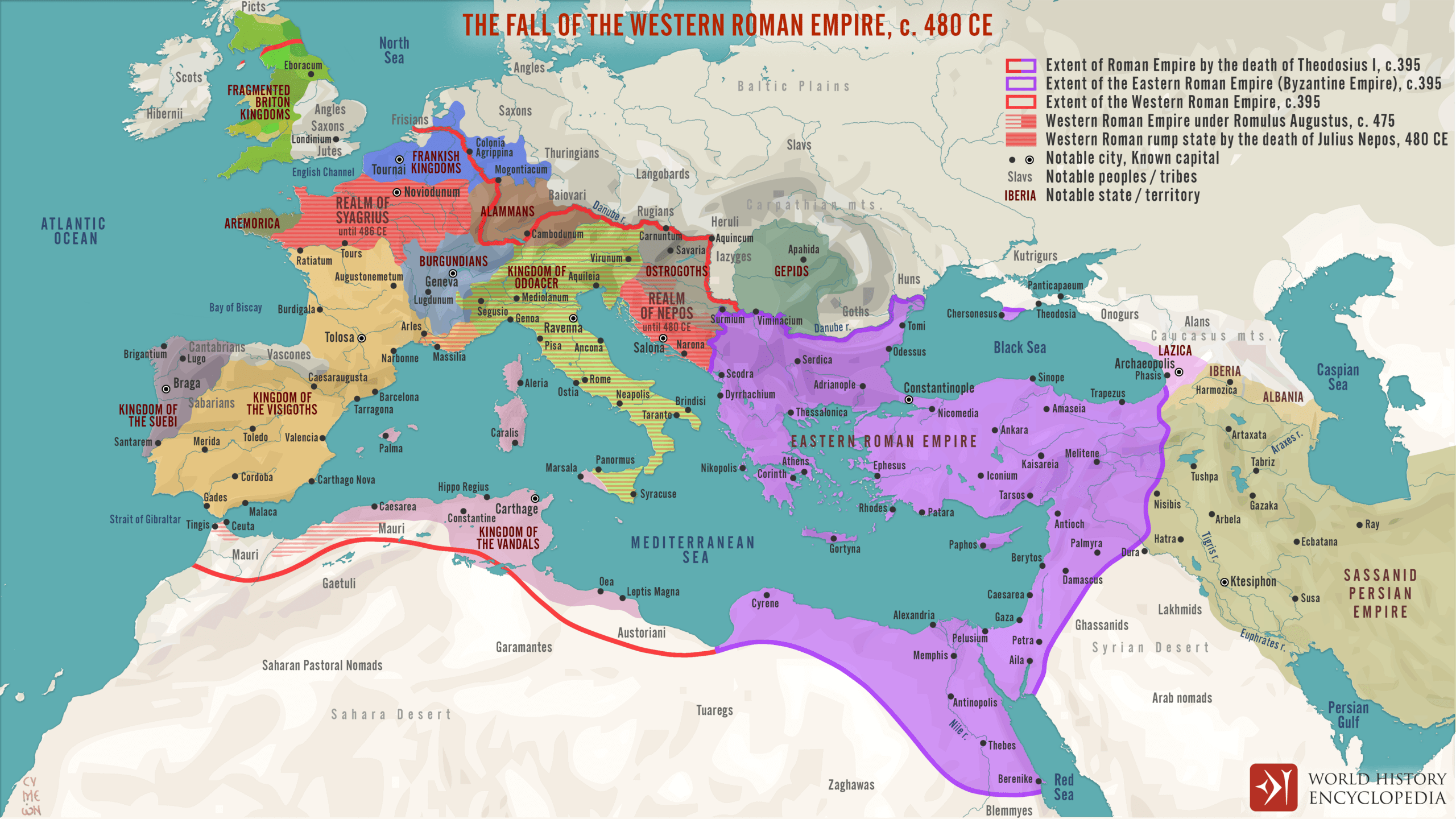

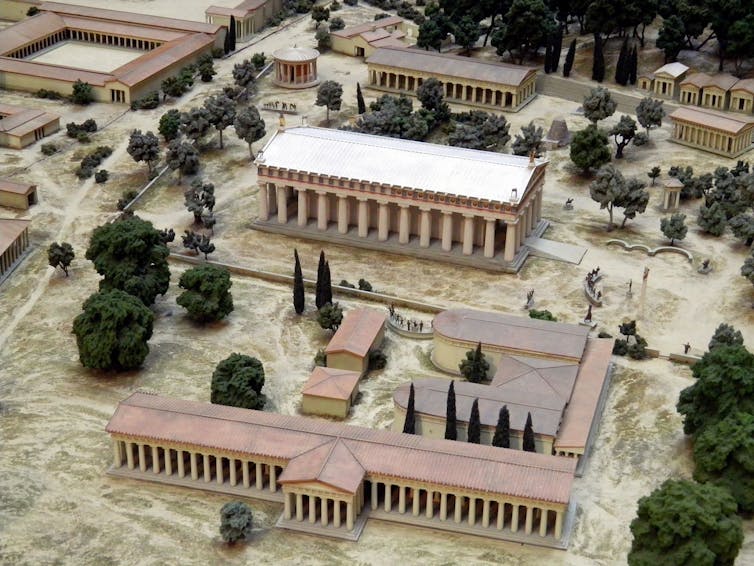

The ancient Games were celebrated not in a city called Olympia but at the sanctuary of Olympic Zeus on the western Peloponnese. They were organised by the city of Elis, which tended the site and provided the hellanodikai (judges) every four years to oversee the proper conduct of the Games.

The competitions were part of a lavish festival to honour the most powerful of the Greek gods and featured sacrifices, processions and dedications. Yet the religious setting did not necessarily ensure a more solemn and respectful attitude on the part of the participants. While most of the athletes stuck to the rules, some were prepared to do whatever it took to secure victory.

The Alexandrian boxer Apollonius arrived at the Games too late and was banned from competing. He claimed that bad weather had made it impossible for him to arrive on time. This was a straight lie: it turned out that Apollonius was late because he had secured himself a nice payout at some other Games.

What happened next was even more outrageous. In the words of the author Pausanias:

In these circumstances the Eleans shut out from the games Apollonius with any other boxer who came after the prescribed time, and let the crown go to Heracleides without a contest. Whereupon Apollonius put on his gloves for a fight, rushed at Heracleides and began to pummel him, though he had already put the wild olive on his head and had taken refuge with the umpires. For this light-headed folly he was to pay dearly.

As in the modern world, who was allowed to compete was crucial; in the ancient world, this meant (for most of the history of the Games) exclusively free Greek males. That was the theory, at least. In practice, there were times the citizens of a particular city were excluded from the Games for misconduct. This is why a Boeotian man once claimed to be from Sparta.

Women were not allowed even to visit the sanctuary during the Olympic Games, let alone compete. They had their own Games, the so-called Heraia. Once a young athlete’s mother managed to sneak in by masquerading as his male trainer. When her son secured the victory, she got overly excited and blew her cover.

Even the judges were not beyond reproach. In the equestrian disciplines, the owner of the winning horse took victory. A certain Troilos was able to win two contests over which he presided as judge. He apparently did not find this problematic: a bronze plaque boasts of his achievements to the rest of the Greek world.

The Eleans subsequently changed the rules, and judges’ horses were no longer allowed to compete.

Fines and prizes

At Olympia, competitors found to be cheating had to pay a hefty fine. The sanctuary featured a row of statues of Zeus – the so-called Zanes – that were financed by these fines and put on display for all to see. Visiting in the second century AD, Pausanias was still able to tell who had financed which statue and for what reason.

Even in the ancient world, it seems, cheating didn’t pay.

So what was at stake? The winner took all. Coming second or third did not rate and brought no public recognition. The winning athlete at Olympia received a crown of olive branches – at Delphi, fresh celery.

If this seems hardly worth the fuss, more lavish rewards waited at home in the form of cash, free meals and numerous public honours. Some winners also received life-size statues erected at Olympia or in their home town, or both.

The possibility of exploiting the Games for political ends and the opportunities for personal aggrandisement were not lost on the ancients: Emperor Nero moved the Games from AD 65 to AD 67 so that he could enter the competitions in chariot racing – which he did, with a ten-horse team.

During the race, the overly keen emperor fell from his chariot and was unable to finish. Nevertheless, Nero was awarded the crown. The officials simply argued that had the accident not happened, the Roman emperor would surely have won.

Nero’s Olympic “achievements” were later removed from the public records and the Games of AD 76 declared null and void. The intervention had been too obvious, particularly after it emerged that Nero had paid the judges a hefty bribe and also awarded them Roman citizenship.

Cheating, bribery and scandal, it seems, were part of the Games right from the start – as were attempts to prevent them. They are not a sign of the decline of the Olympic idea in the modern era, but part of human nature.

For better or worse, it seems, the absolute will to succeed can be absolute indeed and in antiquity just as today ambition cuts both ways, bringing out the best and the worst in people.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Podcasts about the ancient Olympics

Articles you may also like

Weekly History Quiz No.215

1. Troops from which Allied nation spearheaded the 1942 Dieppe raid?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

Weekly History Quiz No.271

1. When was the first Sino-Indian War?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.