Reading time: 5 minutes

The size of the first population of people needed to arrive, survive, and thrive in what is now Australia is revealed in two studies published today.

It took more than 1,000 people to form a viable population. But this was no accidental migration, as our work shows the first arrivals must have been planned.

By Corey J. A. Bradshaw, Laura S. Weyrich, Michael Bird, and Sean Ulm

Our data suggest the ancestors of the Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islander, and Melanesian peoples first made it to Australia as part of an organised, technologically advanced migration to start a new life.

Changing coastlines

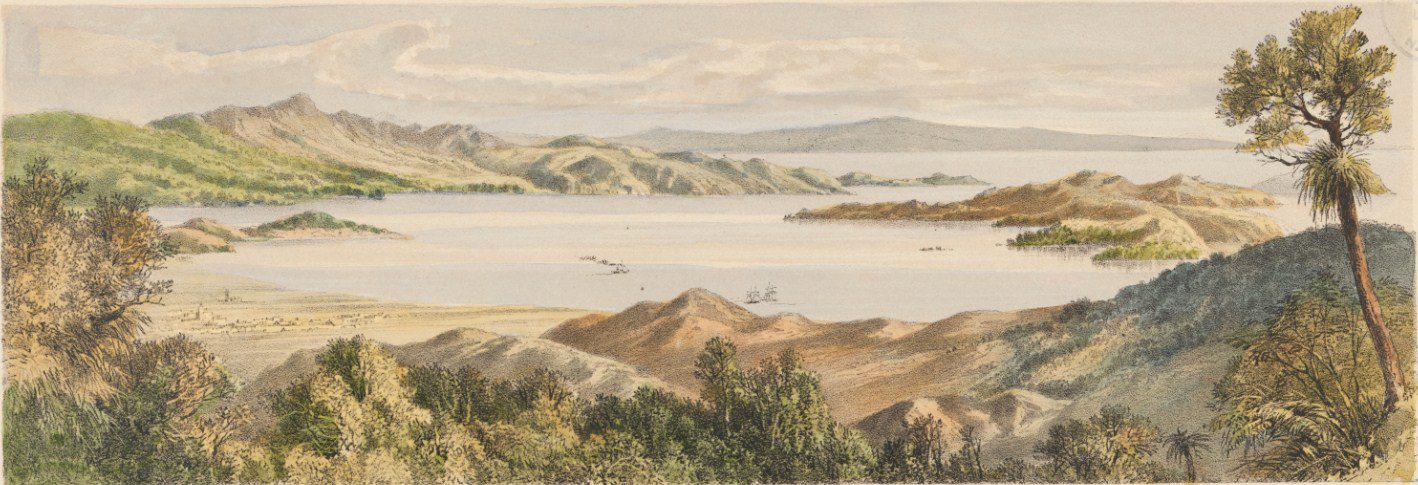

The continent of Australia that the first arrivals encountered wasn’t what we know as Australia today. Instead, New Guinea, mainland Australia, and Tasmania were joined and formed a mega-continent referred to as Sahul.

This mega-continent existed from before the time the first people arrived right up until about 8,000-10,000 years ago (try this interactive online tool to view the changes of Sahul’s coastline over the past 100,000 years).

When we talk about how and in what ways people first arrived in Australia, we really mean in Sahul.

We know people have been in Australia for a very long time — at least for the past 50,000 years, and possibly substantially longer than that.

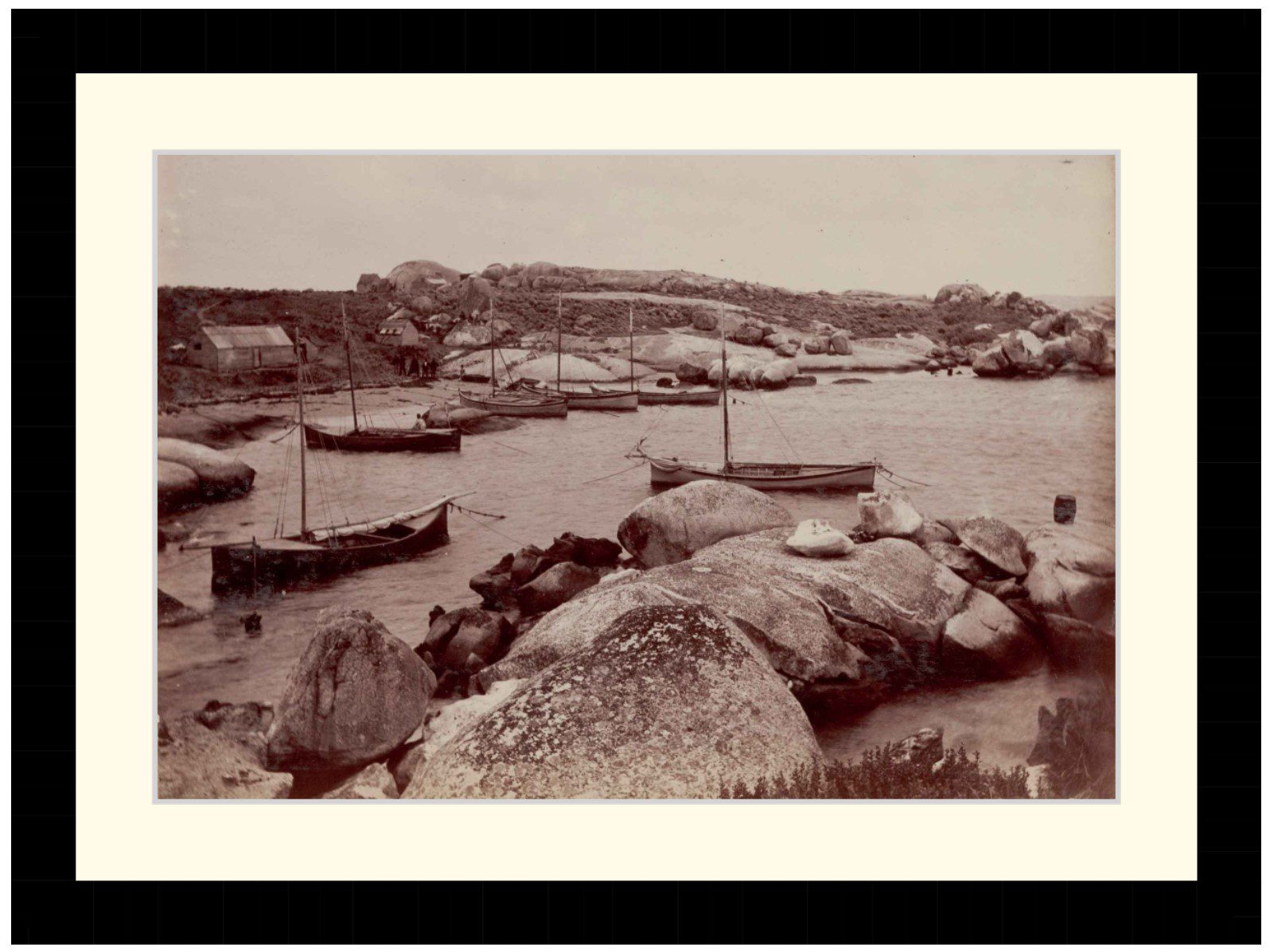

We also know people ultimately came to Australia through the islands to the northwest. Many Aboriginal communities across northern Australia have strong oral histories of ancestral beings arriving from the north.

But how can we possibly infer what happened when people first arrived tens of millennia ago?

It turns out there are several ways we can look indirectly at:

- where people most likely entered Sahul from the island chains we now call Indonesia and Timor-Leste

- how many people were needed to enter Sahul to survive the rigours of their new environment.

First landfall

Our two new studies – published in Scientific Reports and Nature Ecology and Evolution – addressed these questions.

To do this, we developed demographic models (mathematical simulations) to see which island-hopping route these ancient people most likely took.

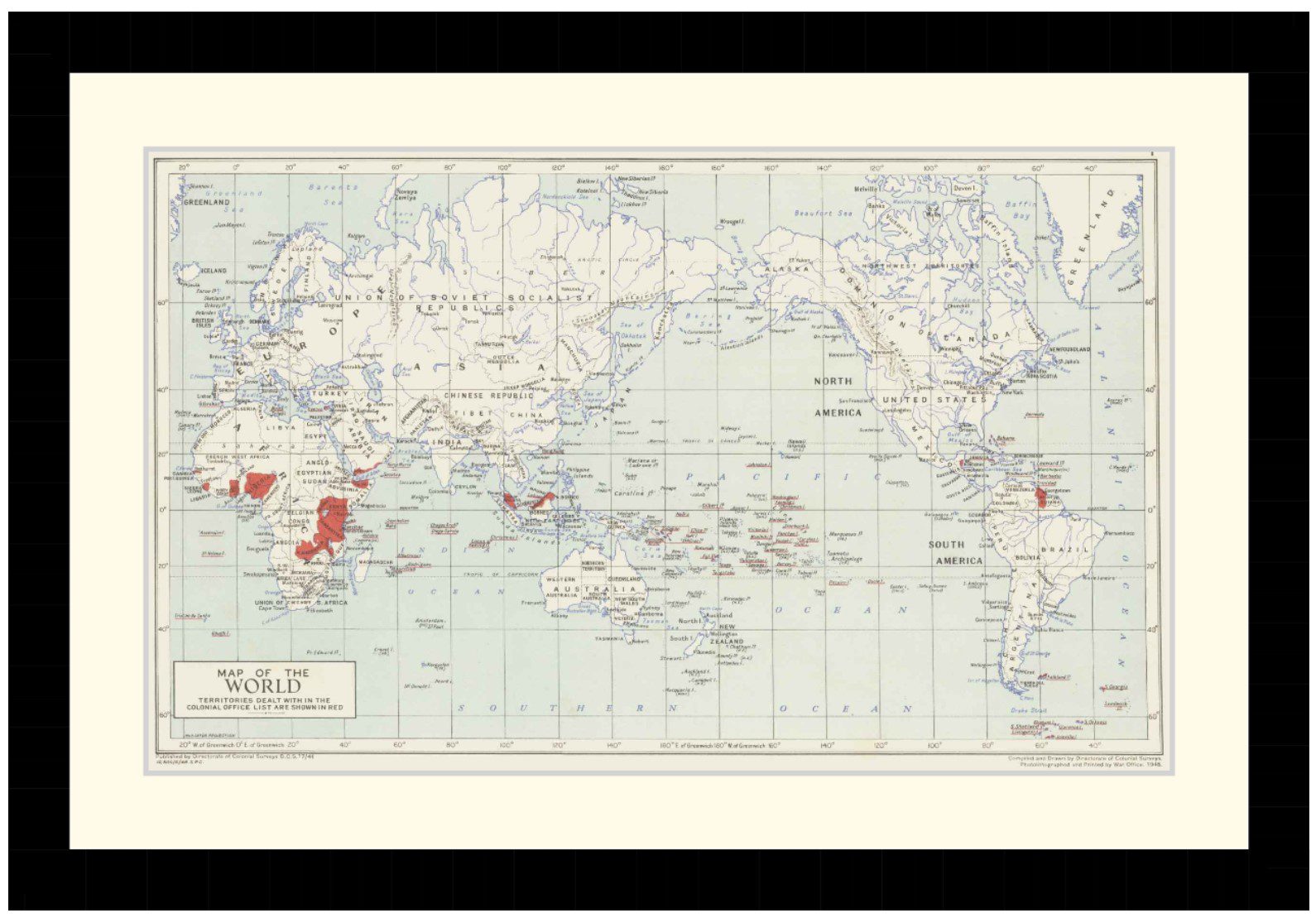

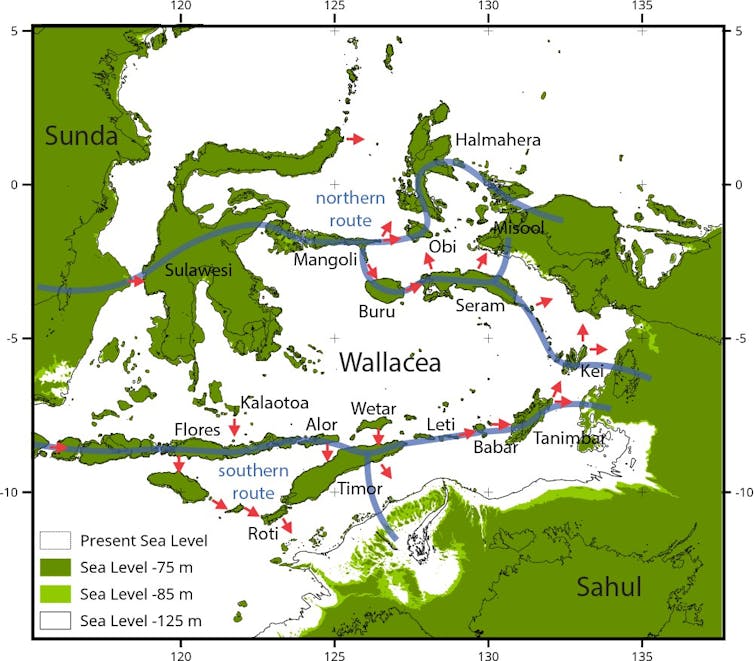

It turns out the northern route connecting the current-day islands of Mangoli, Buru, and Seram into Bird’s Head (West Papua) would probably have been easier to navigate than the southern route from Alor and Timor to the now-drowned Sahul Shelf off the modern-day Kimberley.

While the southern route via the Sahul Shelf is less likely, it would still have been possible.

Modelled routes for making landfall in Sahul. Sea levels are shown at -75 m and -85 m. Potential northern and southern routes indicated by blue lines. Red arrows indicate the directions of modelled crossings. Michael Bird

Next, we extended these demographic models to work out how many people would have had to arrive to survive in a new island continent, and to estimate the number of people the landscape could support.

We applied a unique combination of:

- fertility, longevity, and survival data from hunter-gatherer societies around the globe

- “hindcasts” of past climatic conditions from general circulation models (very much like what we use to forecast future climate changes)

- well-established principles of population ecology.

Our simulations indicate at least 1,300 people likely arrived in a single migration event to Sahul, regardless of the route taken. Any fewer than that, and they probably would not have survived – for the same reasons that it is unlikely that an endangered species can recover from only a few remaining individuals.

Alternatively, the probability of survival was also large if people arrived in smaller, successive waves, averaging at least 130 people every 70 or so years over the course of about 700 years.

A planned arrival

Our data suggest that the peopling of Sahul could not have been an accident or random event. It was very much a planned and well-organised maritime migration.

Our results are similar to findings from several studies that also suggest this number of people is required to populate a new environment successfully, especially as people spread out of Africa and arrived in new regions around the world.

The overall implications of these results are fascinating. They verify that the first ancestors of Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islander, and Melanesian people to arrive in Sahul possessed sophisticated technological knowledge to build watercraft, and they were able to plan, navigate, and make complicated, open-ocean voyages to transport large numbers of people toward targeted destinations.

Our results also suggest that they did so by making many directed voyages, potentially over centuries, providing the beginnings of the complex, interconnected Indigenous societies that we see across the continent today.

These findings are a testament to the remarkable sophistication and adaptation of the first maritime arrivals in Sahul tens of thousands of years ago.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Articles you may also like

Supernova in the East V – Dan Carlin’s Hardcore History

Dan Carlin has just released the latest in his epic Supernova in the East podcast series. Well worth working your way through, earlier episodes of this series are here too if you need to catch up or start from the beginning. Supernova in the East V. Can suicidal bravery and fanatical determination make up for […]

Cretan Resistance During WW2

Reading time: 8 minutes

One of the more impressive feats of arms during the second World War was the way in which the people of Crete fought a guerrilla campaign against the German occupation force. With help from the allies, the Cretans — men, women and even children — fought a brutal and bloody campaign against the invader. In this article, we look at what happened through the eyes of some of the people who participated, Cretan, British and Australian.

The Life of Clara Barton – Volume 1 – Audiobook

THE LIFE OF CLARA BARTON – VOLUME 1 – AUDIOBOOK By William E. Barton (1861 – 1930) Clarissa Harlowe Barton (December 25, 1821 – April 12, 1912) was a pioneering American nurse who founded the American Red Cross. She was a hospital nurse in the American Civil War, a teacher, and a patent clerk. Since nursing […]

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.