Reading time: 6 minutes

At Christmas 1939, Britons had been able to maintain a semblance of normality. The blackout prevented displays of lighted Christmas trees in front windows, but there was no rationing and Britain’s key ally, France, remained unconquered behind the allegedly impregnable Maginot Line.

Following the fall of France, the evacuation at Dunkirk and the Battle of Britain, Christmas 1940 was much bleaker – the first real wartime Christmas. It took place in the middle of the Blitz. In December, the Luftwaffe attacked Southampton, Bristol, Sheffield and Leicester. Manchester took heavy pounding on the night of December 22/23 and again on Christmas Eve. Rationing was beginning to bite hard as the German occupation of Europe and blockade by U-boats cut off important sources of supply.

By Tim Luckhurst, Durham University

As Historian Angus Calder reminds us, in a blatant but compelling propaganda film produced by the Crown Film Unit, Christmas Under Fire, the American correspondent Quentin Reynolds described the atmosphere as the Ministry of Information wished it to be depicted.

“This year” began his script, “England celebrates Christmas underground … The stable in Bethlehem was a shelter too.”

But the nation was determined that its children should enjoy the festive season and Reynold’s sonorous tones insisted that Britain remained “unbeaten, unconquered, unafraid”. The use of carols from King’s College Choir reminded Britain – and the world – that precious traditions endured.

Scrooges and Santas

Contemporary newspapers give a fuller flavour of the public mood. In the mass circulation Daily Mirror on December 16, columnist Kathleen Pearcey worried that women readers might feel guilty about enjoying the festive season. “The idea that giving or going to a party in war time puts you in the Fifth Column Class is fast dying out”, she explained. “To have fun, to dress up, to laugh and play games is sense. It’s Christmas and the only man who matters is coming home on leave.”

The popular left-wing daily did not ignore the hardships imposed by strict rationing. Three days before Christmas, “Voice of the People” columnist Stuart Campbell demanded that the minister for food, Lord Woolton “start a clean-up drive on the people who are making us pay for the war through our stomachs”. Campbell warned that food racketeers were “The Scrooges of 1940.” He accused them of treating Christmas as “a good time to make money” by ratcheting up prices so that only the wealthy could afford festive treats.

But hardship was a reality. Practical gifts such as gardening tools and fertiliser were popular Christmas gifts. In a modest gesture of official generosity, the tea ration was doubled for one week. Imported luxuries such as wine were available only to the wealthy. Nevertheless, the Mirror’s editorial on Christmas Eve insisted:

Nothing except the trump of Doomsday will ever prevent the English people from determining to be “merrie” at Christmas… In this second Christmas of the second war to end war, we hope they will succeed.

Stille nacht

The Conservative establishment Daily Telegraph insisted that life was difficult in Hitler’s Germany too. It republished dispatches sent from Berlin by American correspondents. A story originally filed for the New York Times and reprinted in the Daily Telegraph on Christmas Eve 1940 revealed that Christmas shopping was difficult in the capital of the Reich: “Many articles that in normal times are bought as gifts are not available under the totalitarian war economy.”

The popular Conservative paper Daily Mail took a candid approach. Its Christmas Eve editorial lamented:

We shall not hear the once familiar church bells tomorrow … They are muted, waiting for a sterner call, the summons (please God that it may never come) to defend our homes against the invader.

It was a potent reminder that, despite a morale-boosting recent victory for outnumbered British forces against the Italian Tenth Army at the Battle of Sidi Barrani in early December, the UK was fighting for survival. The Soviet Union remained linked to Nazi Germany by the non-aggression pact of August 1939. The continued presence of American correspondents in Berlin confirmed the reluctance of the US president, Franklin D Roosevelt, to lead his country into war.

On Christmas Eve, the Daily Mail advised its readers that their “first thought” must be for those “to whom no respite of any kind from duty is possible at Christmas or any other time until peace is won”. It identified them as “The RAF, the Royal Navy, men of the Merchant Service, troops under arms, anti-aircraft men at their guns, the Home Guard, ARP Services, wardens and firemen, doctors and nurses.”

The Times, meanwhile, offered a sincere call to Christian piety and reminded its influential readership that while “Christmas makes us realise keenly that war takes away many of life’s pleasant accessories”, our more serious nature should compel us to understand “how trivial these deprivations should seem when the destiny of the world is at stake, how willingly our small sacrifices should be made and how unworthy are grumbles about them.”

From bombed Manchester, the liberal Manchester Guardian offered a glimpse of how the still-new technology of radio could overcome the challenges of distance. It estimated that more than 300 million listeners throughout the British Empire and USA would hear a special BBC broadcast on Christmas Day. Broadcast as “Christmas Under Fire”, this innovative programme united British servicemen around the world.

The Guardian noted that soldiers in Palestine would be heard singing the carol O Come All Ye Faithful “from among the olive trees and vineyards near Bethlehem”.

The Guardian’s report also drew attention to the continuing consequences of mass evacuation. Listeners to Christmas Under Fire would also hear “bombed out London mothers, their children and friends” thanking “their hosts at the end of their first war time Christmas dinner in the country”.

Back in Britain’s battered cities, many families would spend Christmas Eve in air raid shelters.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Podcast about Christmas during the Blitz

Articles you may also like:

Richard O’Connor and Operation Compass: Britain’s Comeback in the Desert

Reading time: 8 minutes

Early in the Second World War, when Britain’s empire stood alone, one man was responsible for the early successes which broke the myth of Axis invincibility. His name was Richard O’Connor.

Neutral and Nervous – A History of Sweden’s Now Broken 200-Year Streak of Neutrality

Reading time: 6 minutes

For over 200 years, Sweden has been one of the few neutral states in Europe. From the Napoleonic Wars and Sweden’s declaration of neutrality in 1812 to today, many conflicts have arisen right on its borders.

Despite this, Sweden (until its joining with NATO in 2024) has successfully navigated neutrality, avoiding two world wars and many other conflicts throughout the 20th Century.

But how did Sweden manage to stay neutral throughout the 1900s with two world wars on its doorstep, and why did it become neutral in the first place?

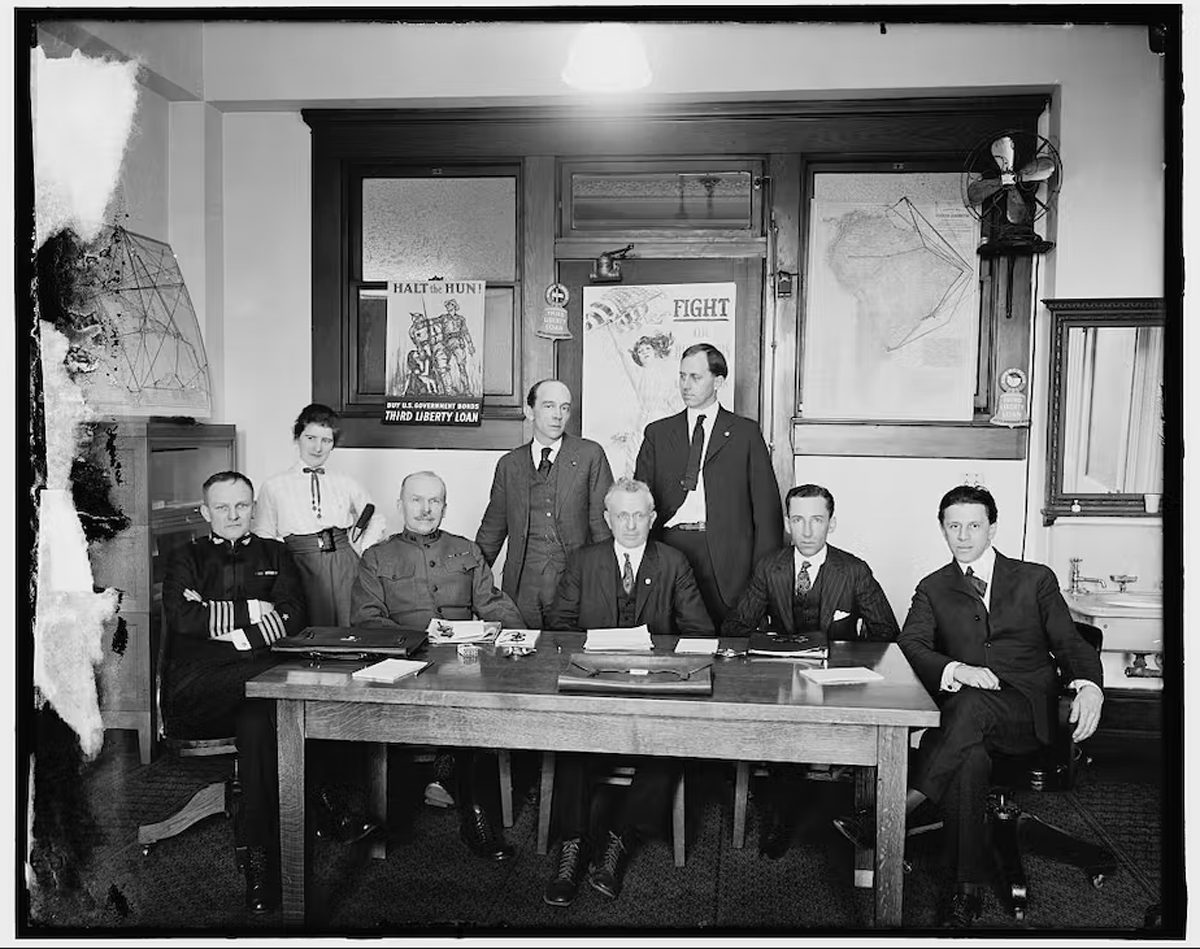

How Woodrow Wilson’s propaganda machine changed American journalism

Reading time: 8 minutes

When the United States declared war on Germany 100 years ago, the impact on the news business was swift and dramatic.

In its crusade to “make the world safe for democracy,” the Wilson administration took immediate steps at home to curtail one of the pillars of democracy – press freedom – by implementing a plan to control, manipulate and censor all news coverage, on a scale never seen in U.S. history.

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.