Reading time: 5 minutes

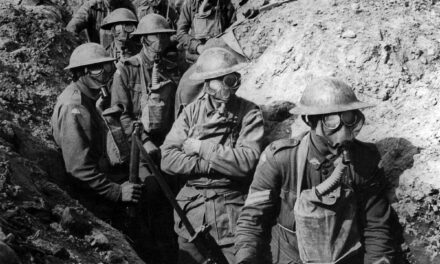

The story of the intelligence war in South Africa during the Second World War is one of suspense, drama and dogged persistence. South Africa officially joined the war on 6 September 1939 by siding with Britain and the Allies and declaring war on Nazi Germany.

South African historians have largely overlooked the intelligence war, partly because of the apparent paucity of reference sources on it. This lack of attention prompted me to investigate the matter further. The result was my book Hitler’s Spies: Secret Agents and the Intelligence War in South Africa.

By Evert Kleynhans, Stellenbosch University

The book offers a new perspective on this lesser known episode of South African history.

After six years of research at various archival depots in South Africa and the United Kingdom, I was able to provide a fresh account of the German intelligence networks that operated in wartime South Africa. My book also details the hunt in post-war Europe for witnesses to help the South African government bring charges of high treason against those who aided the German war effort.

My research shows how, during the war (1939 to 1945), the German government secretly reached out to the political opposition in South Africa, the Ossewabrandwag (oxwagon sentinels). This group was founded as an Afrikaner cultural organisation in Bloemfontein in 1939. During the war, the movement became decidedly anti-imperial and increasingly militaristic. The government regarded it as the proverbial “enemy within”.

The Germans were especially interested in naval and political intelligence. Accurate naval intelligence on ships from Europe and the Far East rounding the Cape of Good Hope, South Africa’s southernmost point, would allow German submarines to attack them.

Political intelligence could further help the Germans to spread sedition within the then Union of South Africa. At the time, this was a dominion – a self-governing entity within the British Empire with English and Afrikaner populations. German agents were dispatched across the globe during the war to collect military and political intelligence. These agents undermined the overall Allied war effort to varying degrees of success.

Hitler’s spies in South Africa

A network of German agents was established in South Africa with the help of the Ossewabrandwag. These agents used a variety of channels to send coded messages to German diplomats in neighbouring Mozambique for onward transmission to Berlin. Due to the neutrality of Portugal during the war, Mozambique, then a Portuguese colony, was a safe haven for German agents and diplomats in southern Africa.

By mid-1942 a radio transmitter was built by the Felix Organisation with the help of the Ossewabrandwag and located near Vryburg, a large farming town in what is now South Africa’s North West province. The Felix Organisation was headed by the agent Lothar Sittig and was the premier German intelligence organisation in wartime South Africa. This radio transmitter eventually allowed for direct, two-way radio contact between agents and Berlin.

But the cooperation between the Ossewabrandwag and the German agents did not go unnoticed.

Through the combined efforts of the South African authorities, all illicit wireless communications between South Africa, Mozambique and Germany were intercepted and decoded.

The British and South African authorities were thus aware of the full extent of contact and cooperation that existed between key members of the Ossewabrandwag and the German agents operational in South Africa. They planned several unsuccessful raids on the illicit radio transmitter near Vryburg. These largely failed due to the dubious loyalties of some of the members involved.

This is evidenced by the existence of several British Security Service (MI5) case files at the National Archives of the United Kingdom. These are filled to the brim with documentary evidence detailing every minute aspect of this episode in South African history.

Consequences

Following the war, the South African authorities were anxious to charge known war criminals, traitors and collaborators. Missions headed by the state prosecutors Rudolph Rein and Lawrence Barrett were established to interview key suspects and collect evidence with the view of bringing criminal charges against known South African traitors and collaborators.

The Barrett Mission was particularly interested in the charismatic leader of the Ossewabrandwag, Hans van Rensburg. He, along with a trusted inner circle, acted as the nodal point for German agents operating in wartime South Africa. A case of high treason was built against Van Rensburg.

The case was terminated following the 1948 electoral victory of the National Party, which would go on to formalise apartheid. Van Rensburg disappeared from the political scene in South Africa soon thereafter. The Ossewabrandwag movement was dissolved in 1952.

It seems the post-war drive towards greater Afrikaner unity proved more important than charging fellow Afrikaners with high treason, despite the overwhelming evidence against them.

After 1948 there was a determined move towards reconciliation within the Afrikaner community. This culminated in the formal establishment of the Republic of South Africa in 1961.

With the passage of time these wartime events all but vanished from the South African collective memory. Gatekeeper mentality at archives, missing documents and the removal of key evidence from public circulation combined to stymie further research on this topic. The high treason docket against Van Rensburg, for instance, was deposited at the National Archive in Pretoria in 1948. It was placed under embargo for an undisclosed period. This document has since gone “missing”.

My book proves, however, that the missing narrative on the intelligence war in South Africa can be reconstructed.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Podcasts about German Spies in South Africa

Articles you may also like

How the world failed West Papua in its campaign for independence

Reading time: 6 minutes

At the UN, West Papuan activists sought the support of African delegates who they believed were likely allies. They argued West Papua and Africa shared a history of racial oppression and a desire to see the end of colonialism in all its forms.

The Only Two Submarines to Sink Enemy Ships Since WW2

Submarines played a very important role in WW1 and WW2 but there has only been successful in combat twice since then. This video examines these two engagements.

The East River Column: the rebels who helped Second World War prisoners of war

Reading time: 13 minutes

The underground resistance group the East River Column played a vital role opposing Japanese forces around Hong Kong during the Second World War. Their activities provided a lifeline for Allied prisoners of war, who they aided with support, shelter, and a means of escape.

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.