TONGERLONGETER — THE TASMANIAN RESISTANCE FIGHTER WE SHOULD REMEMBER AS A WAR HERO

Reading time: 3 minutes

Australians love their war heroes. Our founding myth centres on the heroism of the ANZACs. Our Victoria Cross recipients are considered emblematic of our highest virtues. We also revere our dissident heroes, such as Ned Kelly and the Eureka rebels. But where in this pantheon are our Black war heroes?

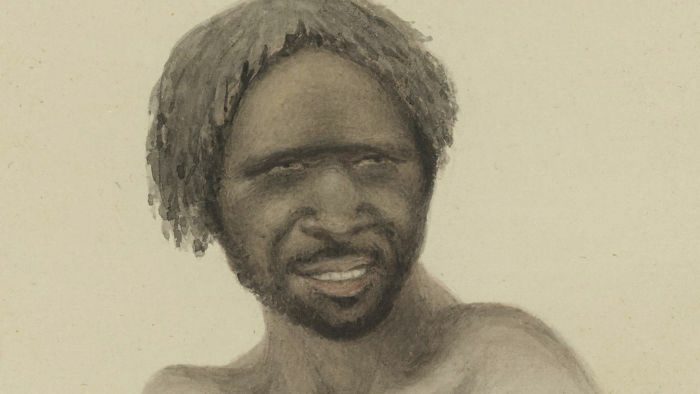

If it’s underdog heroism we’re after, we need look no further than the warriors who resisted the invasion of their homelands between 1788 and 1928. And none distinguished himself more than Tongerlongeter — the subject of a new book I have written with historian Henry Reynolds.

By Nicholas Clements, University of Tasmania.

Tongerlongeter’s story

In Tasmania’s “Black War” of 1823–31, Tongerlongeter led a stunning resistance campaign against invading British soldiers and colonists. Leader of the Oyster Bay nation, he inspired dread throughout the island’s southeast. Convicts refused to work alone or unarmed, terrified settlers abandoned their farms, the economy faltered and the government seemed powerless to suppress the violence.

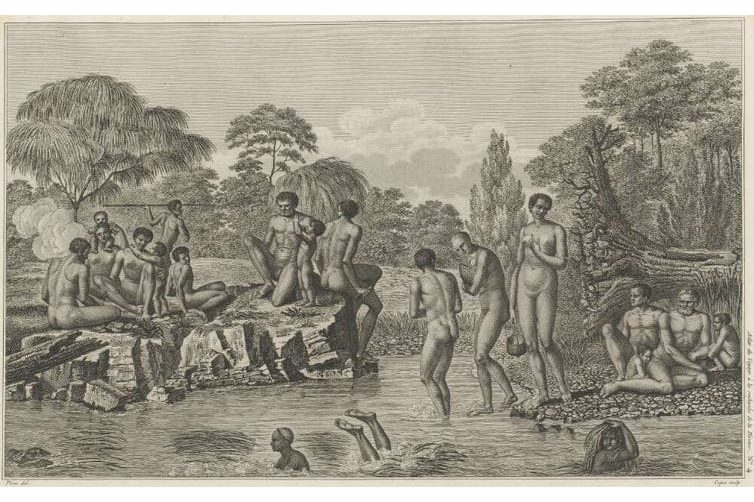

It was a legacy Tongerlongeter could never have imagined in 1802, when his people encountered the French explorers under Nicolas Baudin on Maria Island. Having never heard of foreign lands or peoples, they concluded the pale-faced visitors were ancestral spirits returned from the dead. If zombies are an apt comparison, they were soon to experience a zombie invasion.

The British established their first settlement at Risdon Cove, opposite today’s Hobart, in 1803. Only from the 1820s did settlement accelerate up the fertile valleys of the southeast. Tongerlongeter initially restricted his warriors to targeted retribution, but as the violence intensified, all stops were pulled.

By night, Tongerlongeter and his people were vulnerable to ambushes. Gangs of frontiersmen and sealers killed hundreds of men and abducted countless women and girls. Tongerlongeter’s first wife was taken in just such an ambush.

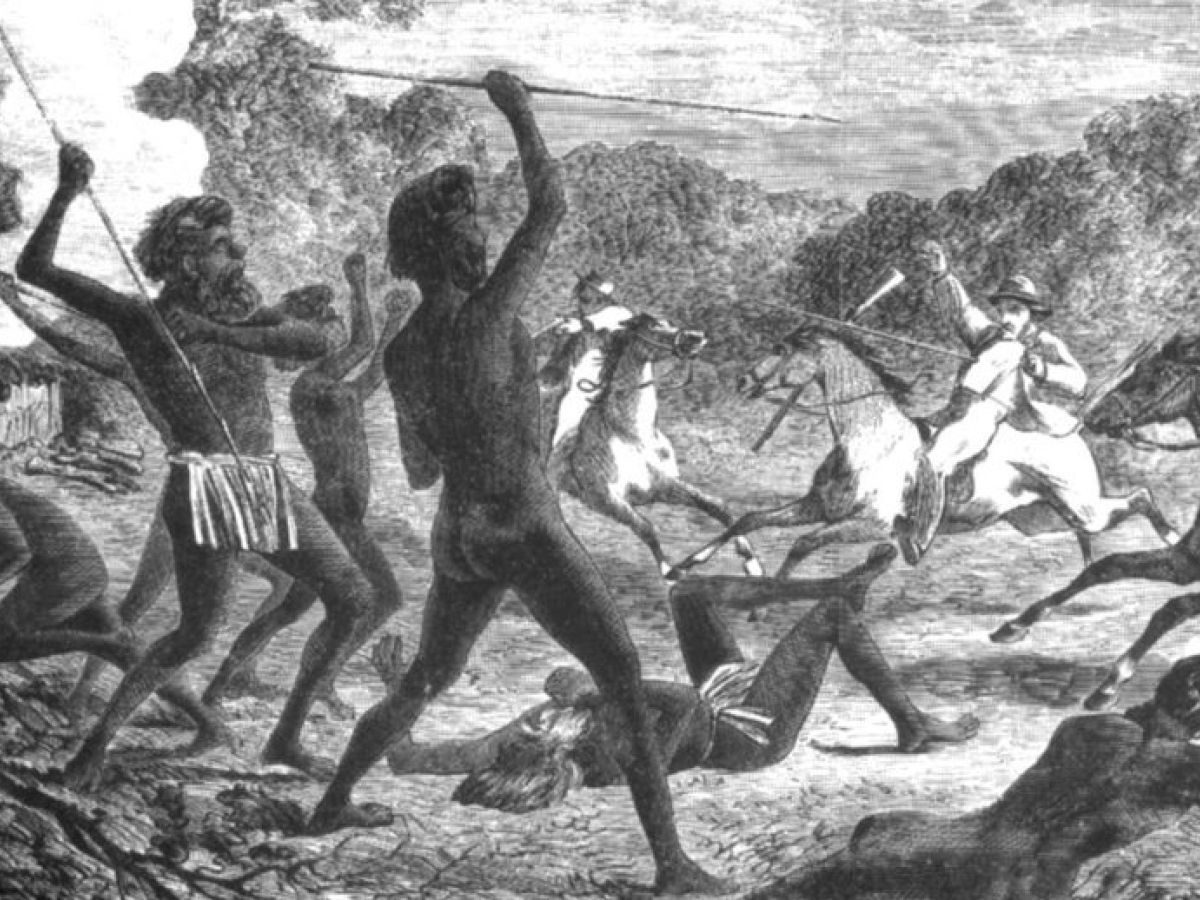

Being wary of evil spirits, Tongerlongeter’s people never attacked by night. But from sun-up to sun-down, exposed colonists lived in constant fear of attack. Using sophisticated tactics such as reconnaissance, decoys, flanking and pincer manoeuvres, sabotage, and arson, Tongerlongeter’s war parties attacked hut after hut, and often several at a time.

Trained from infancy in the arts of war, Aboriginal warriors carried out guerrilla operations with extraordinary discipline and strategy. Apart from soldiers, most colonists were woefully unprepared to face such assailants. Typically, warriors would surround a hut, then kill its occupants, plunder whatever they wanted, and set it alight. Then they “simply vanished”, outwitting even mounted pursuit parties.

In 1828, as the body count rose, Lieutenant Governor George Arthur declared martial law. Vigilantes had long “hunted the blacks” with impunity; now they did so legally.

While such measures took a devastating toll, Tongerlongeter and his allies, the neighbouring Big River nation, only intensified their resistance, making 137 documented attacks in 1828, 152 in 1829, and 204 in 1830. Each year they refined their tactics. Some settlers insisted the colony should be abandoned.

This article was originally published in The Conversation

Articles you may also be interested in

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.