Reading time: 13 minutes

When a plan to overthrow English rule in Ireland was foiled in the 1860s, hundreds of Fenian rebels were arrested and convicted. A handful of those were condemned to transportation to Australia with no hope of pardon or of ever seeing their families again.

By Morgan W. R. Dunn

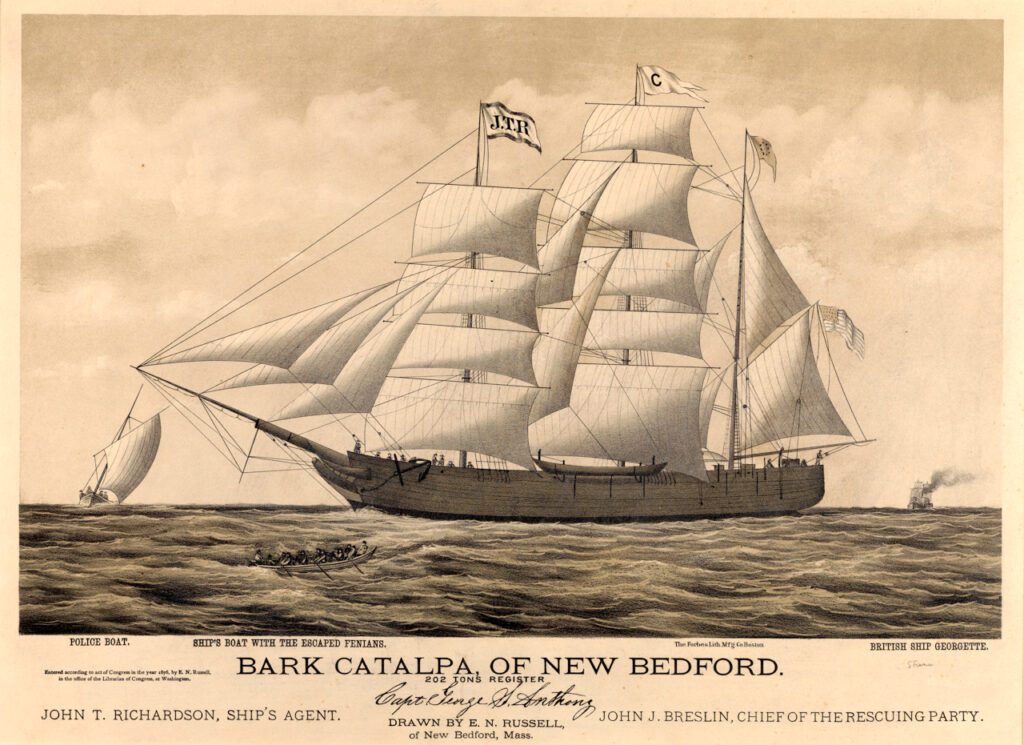

Moved by their plight, a radical Irish journalist championed a daring plan to send a ship, the Catalpa, around the world to spirit the convicts to safety.

The Fenian Plot Foiled

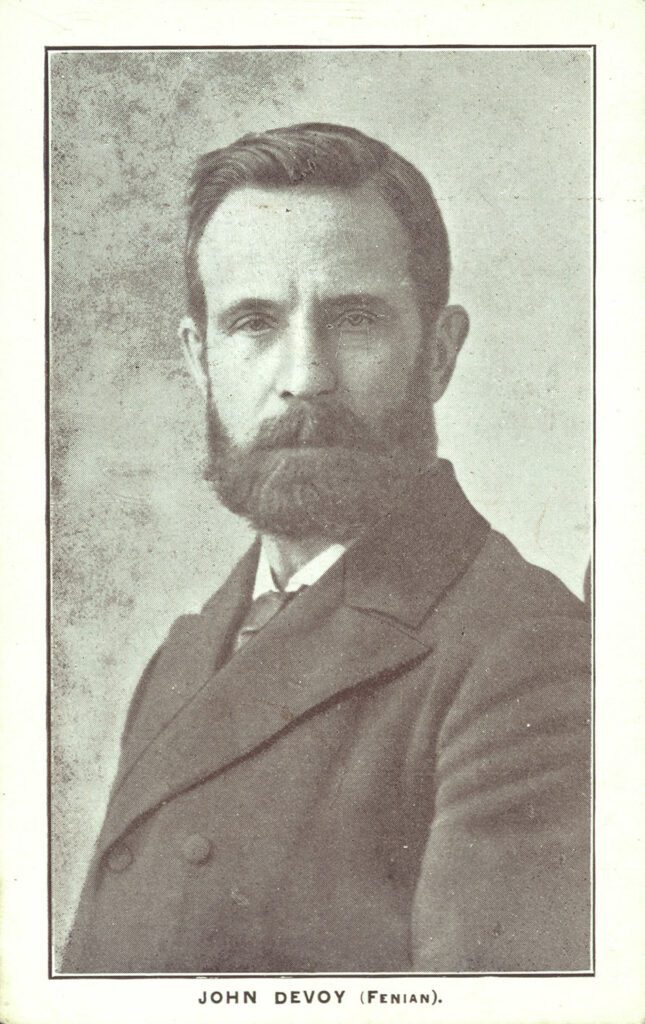

After five years in Portland Prison, John Devoy was released and banished from England. Devoy was a Fenian, a rebel against English rule in Ireland named for the warrior companions of the mythical Irish hero Fionn mac Cumhaill. In 1866, Irish veterans of the American Civil War were seen as a force with which to finally achieve Irish independence. Fenian leadership was hesitant, and informers soon alerted British authorities to the plot. Over the next two years, Devoy and hundreds of others were arrested.

Among those the Fenians had recruited were Irish soldiers in the British Army. Civilians were sentenced to 15 years’ imprisonment; 16 arrested soldiers, however, were court-martialed and sentenced to death.

When Devoy and the other civilians were released and exiled under amnesty in 1871, “the Duke of Cambridge, Commander-in-Chief of the British army, interposed an objection against the military prisoners and his word was law with his august cousin Queen Victoria. Releasing these Fenian soldiers, he said, would be subversive of discipline in the army.”

Instead, the soldiers’ sentences were commuted to a punishment which was even then fading from British law: transportation to Australia. Eight were given life sentences.

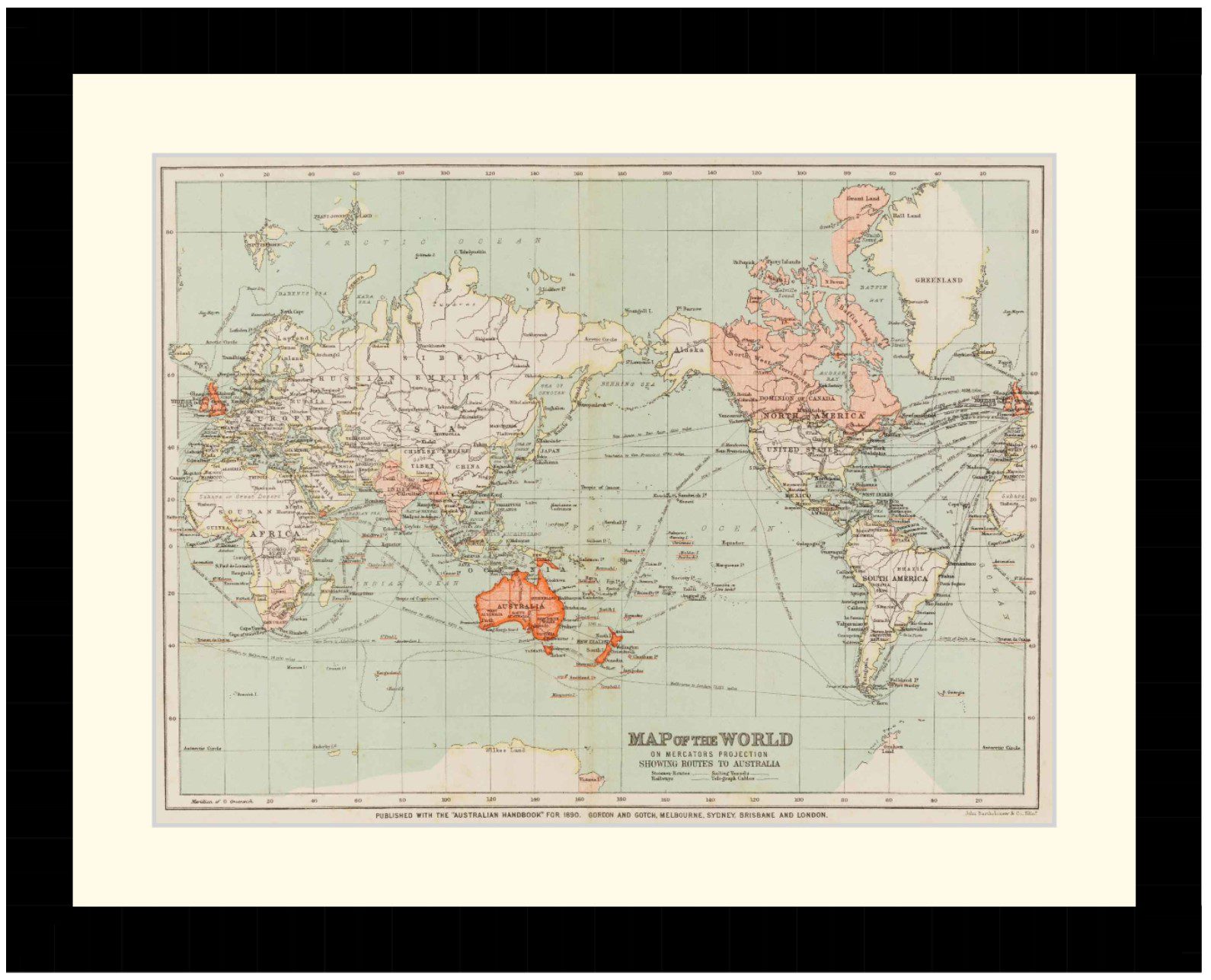

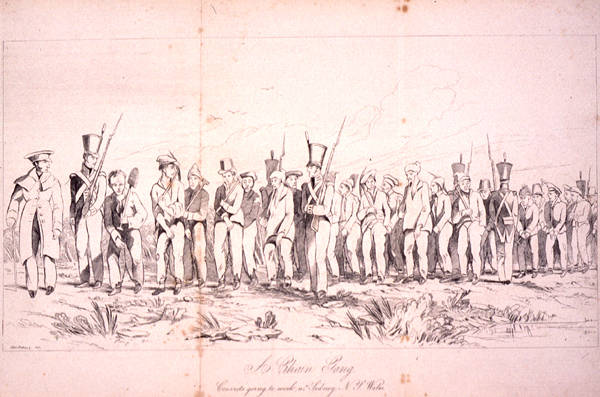

In October, 1867, 280 prisoners, including 62 Fenians, among them the convicted soldiers, were chained and loaded aboard the convict ship Hougoumont. Three months and 11,000 miles later, the Hougoumont disgorged its human cargo at Fremantle, Western Australia, on 10th January 1868. It would be the last ship ever to transport prisoners to the continent.

The Fate of the Military Fenians

In New York, Devoy recalled, “a public reception was given to them under the auspices of the Clan-na-Gael” (a US-based Irish republican organisation). The “military Fenians,” on the other hand, were assigned to work gangs for hard labour.

The Fenians stood apart from the dwindling convict population of Australia. The rarity of political prisoners in Australia was illustrated by statistician L. L. Robson: “one-half to two-thirds of the convicts carried previous convictions. Eight in ten were thieves, and only a minuscule fraction could be classed as political offenders.”

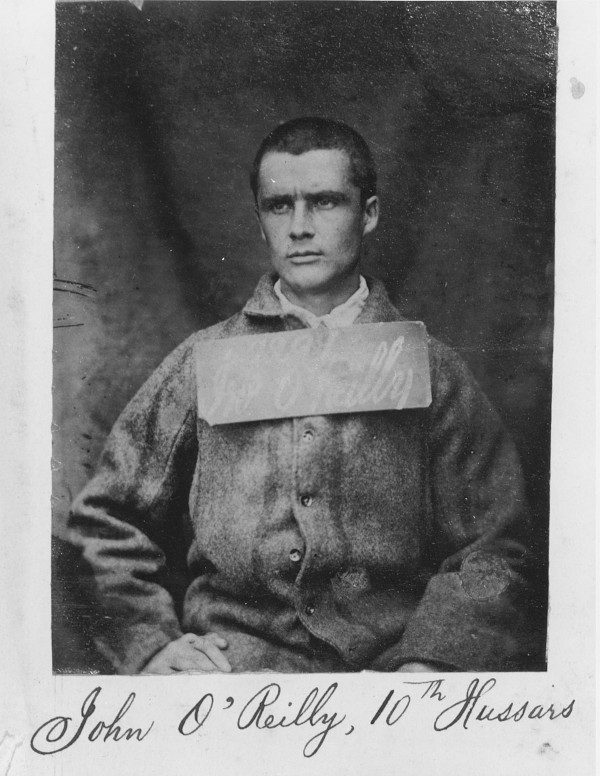

John Boyle O’Reilly, a veteran of the 10th Royal Hussars, drew attention by refusing to cut down a tuart tree as part of a road construction gang near Bunbury. This eventually led to his promotion to trustee, a prisoner with administrative duties and freedom of movement. He was thus able to escape aboard the American whaler Gazelle, reaching Philadelphia in November 1869.

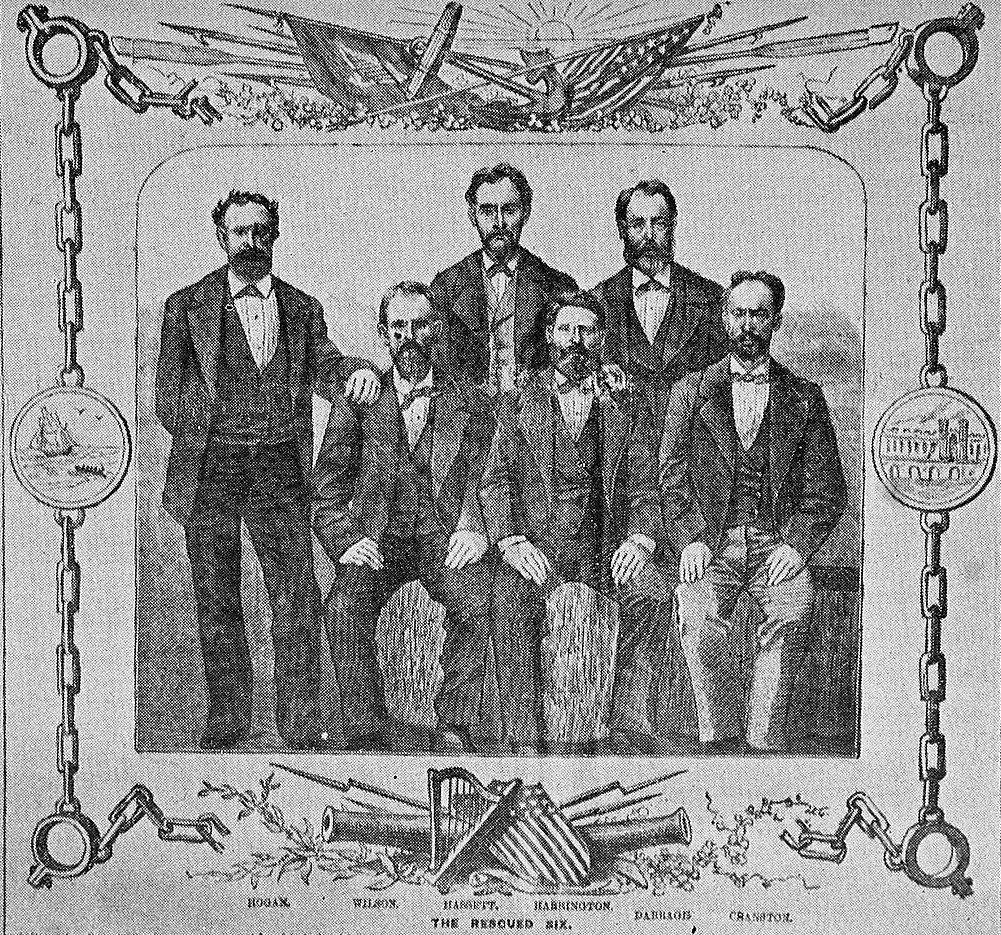

Sergeant Major Thomas Darragh of the Queen’s Royal Regiment had less considerate treatment: Governor Dr. John Hampton informed his staff that Darragh was “not a Fenian but a military prisoner and you will treat him as an ordinary felon.”

Martin Hogan worked in a Perth quarry and walked off the job away from an abusive warder. Michael Harrington, the oldest of the group and a veteran of the Indian Rebellion of 1857, was assigned to general labor, as was Robert Cranston, of the 61st Regiment of Foot. Thomas Hassett, a veteran of the 24th Regiment of Foot, absconded for 10 months and was then sentenced to six months’ solitary confinement and three years’ hard labor. James Wilson enlisted at 17 to escape arrest for beating a policeman.

In February 1869, and again in 1871, the House of Commons granted a free pardon to all the Fenians transported to Western Australia. The 16 military prisoners were excluded. O’Reilly, Darragh, Harrington, Hassett, Cranston, and Hogan faced the prospect of never again seeing their homes or families, enduring years in shameful exile doing backbreaking work.

A Voice from the Tomb

In 1871, Devoy received a letter from Hogan, who described the harsh punishment and his wish to get away. For three years, Devoy could only canvass supportfor a plan to aid the convicts.

Finally, in 1874, Wilson smuggled a desperate letter to New York:

“Dear Friend, remember this is a voice from the tomb. For is not this a living tomb? In the tomb it is only a man’s body that is good for worms, but in the living tomb the canker worm of care enters the very soul… We ask you to aid us with your tongue and pen, with your brain and intellect, with your ability and influence, and God will bless your efforts, and we will repay you with all the gratitude of our natures… our faith in you is unbound. We think if you forsake us, then we are friendless indeed.”

Stung by Wilson’s lament and conscious that it was for him and the other Fenian leaders that the soldiers had been transported, Devoy approached the July 1874 Clan na Gael convention and requested that something be done. This time, the delegates agreed.

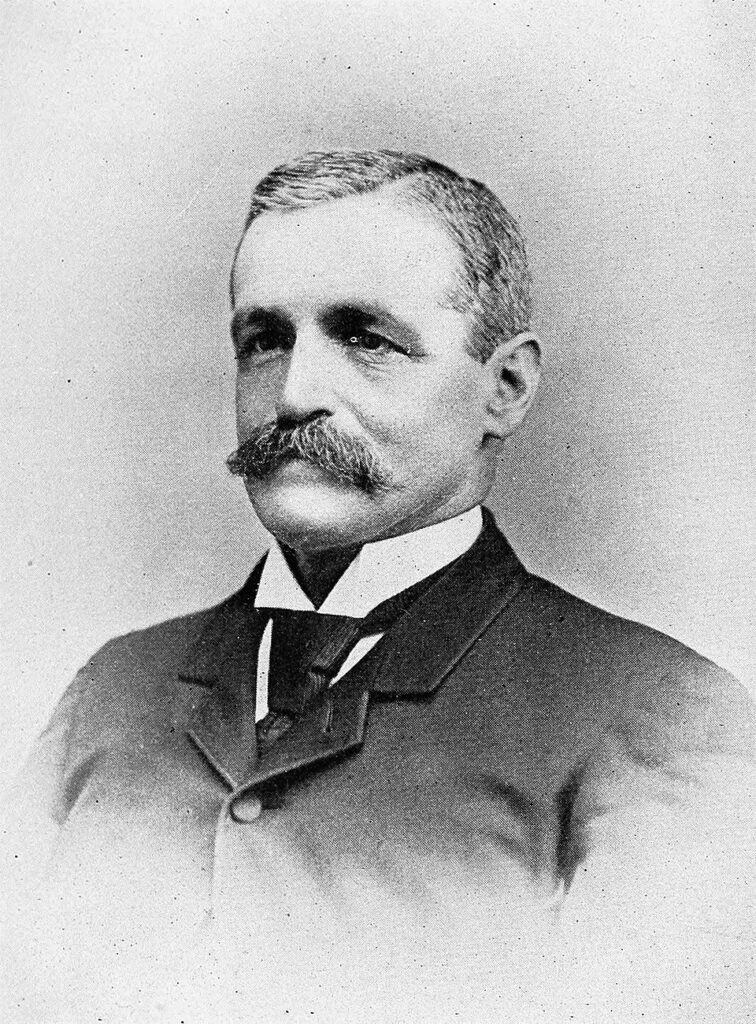

Thomas Fennell, a pardoned Fenian who’d left Western Australia in 1871, suggested a merchant ship be chartered and sent across the Pacific to retrieve the men. The ship they settled on was the Catalpa. Purchased through subscriptions for $5,250, it was to be captained by George S. Anthony of New Bedford, Massachusetts.

“Though built originally as a whaler,” Devoy recalled, “the Catalpa had for some years previously been engaged in the West India trade, and several important changes were necessary. A blubber deck had to be constructed, she had to be coppered, whaling boats had to be built. Some sails, an anchor, a chronometer, as well as all accessories for a whaling expedition such as oil, watercasks, harpoons, bomb-lancers, medicine chest, etc., were also provided.”

In April 1875, the vessel was finally ready and a Clan na Gael representative, Dennis Duggan, appointed to the crew as carpenter. Two more Fenian agents, John Breslin and Thomas Desmond, traveled separately to Australia to prepare the escape.

Escape to the Catalpa

Anthony hunted whales in the Atlantic for five months, and from the Azores proceeded to Australia. Breslin, as American businessman “James Collins,” and Desmond, under the name Johnson, reached Fremantle on 16th November 1875.

Desmond took a job in Perth, while Breslin became known as a respectable millionaire, moving into the upper circles of Western Australian society. He even befriended Fremantle prison’s superintendent and the colonial governor, Sir William Robinson, who gave him a tour of the prison. Breslin alerted Wilson through Fenian ex-prisoner William Foley, telling the prisoners that “We have money, arms and clothes; let no man’s heart fail him, for this chance may never come again”.

Delayed by desertion and bad weather, the Catalpa dropped anchor off Bunbury on 29th March 1876. Captain Anthony and Breslin immediately met, and settled on Easter Monday, 17th April 1876, as the date of the escape.

Aboard the Catalpa, the crew were kept busy overhauling the ship to buy time. Rockingham, near Perth, was chosen as the point of departure when it became known that a Royal Navy gunboat was near Bunbury.

On the morning of the 17th, the six Fenians able to escape were working outside the walls of the prison. Cranston told a warder that he, Wilson, and Harrington had been detailed to move some furniture in the governor’s house. Darragh, Hassett, and Hogan walked in the direction of their worksite. Just after 8 o’clock, Cranston, Wilson, and Harrington were picked up in a carriage driven by Desmond. Breslin then picked up Darragh, Hassett, and Hogan in another.

The party tore over 20 miles (30 km) south to Rockingham Pier, where Captain Anthony awaited with one of his whaleboats, arriving just after 10:30. The quick progress was partly due to disguises provided by Breslin and Desmond and their status as trusted long-serving men, constables of the convict establishment. When they reached Rockingham, however, they were spotted by local farmer James Bell, who alerted the formal authorities to the escape.

A Heated Pursuit

Once the party was aboard, Anthony gave the order to “’Out oars and pull for your lives! Pull as if you were pulling after a whale!” The Catalpa was anchored miles off the coast in international waters, through which the boat would have to travel for much of the rest of the day. A squall struck the boat at about 7 o’clock that evening, breaking the mast. Finally, after a harrowing night on open water, they spotted the whaler again at 7 o’clock the next morning and rowed furiously for it.

As they were drawing close, Desmond spotted what he quickly realised was the SS Georgette, a coastal steamer which Governor Robinson had commandeered to pursue the fleeing prisoners. The whalemen armed themselves; the prisoners lay down in the hull. Unnoticed, they saw the Georgette move off and again made for the Catalpa.

By 2 pm, they were finally closing in when they saw an armed police cutter approaching. The two vessels raced to reach the whaler first; the whaleboat won, coming alongside at 3 o’clock as the men “scrambled on board in double quick time” within sight of their pursuers.

The order was given to weigh anchor and move off. But on the morning of the 19th, the Georgette, freshly refueled and rearmed under a British naval ensign, steamed ahead of the Catalpa and fired a shot across the bow. A tense exchange followed, with the Georgette’s captain demanding the prisoners’ return.

“‘I give you fifteen minutes to consider,” said the captain in Devoy’s account, “and you must take the consequences; I have the means to do it, and if you don’t heave to I’ll blow the mast out of you.’”

“Captain Anthony shouted a reply pointing to his flag. ‘That’s the American flag; I am on the high seas; my flag protects me; if you fire on this ship you fire on the American flag.’”

The pursuers hesitated and made a final demand after the 15 minutes were up, but they obeyed Governor Robinson’s strict orders not to start an international incident. At 9:30 am, beaten, they turned back for Fremantle.

A Victory for Fenianism

Word of the successful escape reached O’Reilly in June, overjoying Irish Americans. Four months to the day after the final encounter with the Georgette, on 19th August 1876, the Catalpa pulled into New York to a heroes’ welcome.

The following month, The Pilot, the newspaper O’Reilly edited, reported that:

“On the 1st inst. [1st September], a grand entertainment was given in Music Hall for the benefit of the released prisoners… nearly every seat on floor and galleries was filled.” Five of the six escapees were present, with James Wilson represented by William Foley, his contact in Fremantle.

None of the Catalpa Six ever returned to Ireland. Although exiled from British domains for the rest of their lives, they spent those lives as free men. Robert Cranston married and settled in Philadelphia. Thomas Hassett married and became a saloon keeper in New York. Michael Harrington also married and became a police officer in New York City. Martin Hogan moved to Chicago, married, had a daughter, and became a painter. Thomas Darragh became a teamster and died in Philadelphia in 1912.

John O’Reilly continued working at The Pilot, and had notable success as a novelist, lecturer, and poet.

John Devoy, the coordinator of the escape, carried on agitating for Irish independence for decades. He returned to Ireland in 1924, by which time 26 of Ireland’s 32 counties had become the autonomous Irish Free State.

For years afterwards, Western Australians embraced a song which celebrated the escape of the Catalpa:

A noble whale ship and commander,

Called the Catalpa they say,

Came out to Western Australia,

And took six poor Fenians away.

So come all you screw warders and gaolers,

Remember Perth Regatta Day;

Take care of the rest of your Fenians,

Or the Yankees will steal them away.

Frustrated authorities allegedly attempted to suppress its singing. They failed.

Podcast Episodes about the Catalpa Prison Escape

Articles you may also like

Menin Road – Podcast

In 1917, General Haig began what would become known as the Third Battle of Ypres, with the intention of capturing the village of Passchendaele. But getting to the village would require a series of bite-and-hold battles. In September, the 1st and 2nd Australian Divisions, along with British and South African Divisions, launched the third in the series of assaults, at Menin Road. For the first time in history, two Australian divisions would be fighting side-by-side. If they were to ever have this chance again, they would have to prove just how formidable they could be.

‘I want to scream and scream’: Australian nurses on the Western Front were also victims of war

The revival of interest in Anzac since the 1980s has depended in part on the repositioning of soldiers as victims. We rarely celebrate their martial virtues, and instead note their resilience, fortitude and suffering. This shift in emphasis opens up more promising space for the inclusion of women. Nurses were not warriors – they were […]

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.