Reading time: 11 minutes

In 1926, a newly-unified China had millions of men under arms, but few who could wield them effectively. Determined to make the country ready to defend itself, Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek turned to an unusual ally.

By Morgan WR Dunn

For a decade, officers and experts from Germany’s Reichswehr oversaw the transformation of China’s army. While their plans were never fully realised, they had a significant impact on the war to resist Japanese invasion.

A COUNTRY IN RUINS

In 1911, an impromptu rebellion broke China’s ageing Qing Dynasty apart. But before the new republic could find its feet, the same modernised armies the Qing had established to defend the country splintered into dozens of petty factions, each headed by officers dedicated only to their own power and privilege.

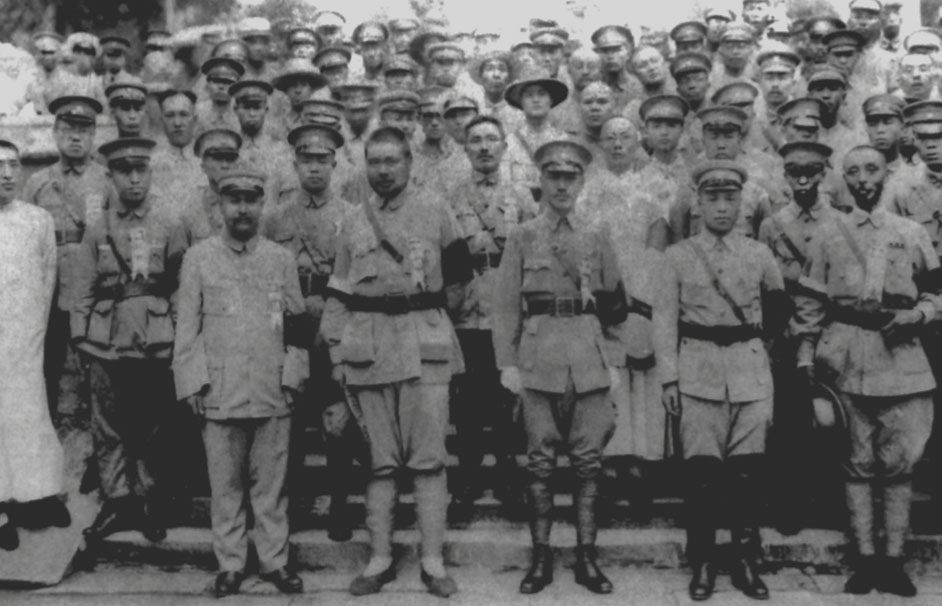

For years, the Warlord Era tore China apart from within. But in 1926, a young Japanese-trained officer, Chiang Kai-shek, leader of the Kuomintang (KMT), or Nationalist Party, devised an ambitious plan. Chiang was commandant of the Whampoa, or Huangpu, Military Academy, a modern school set up by the Soviets, who’d sent a mission to modernise the KMT’s military forces.

Chiang’s Northern Expedition was the beginning of a slow end for the warlords. Within a year he’d defeated many major warlords and captured dozens of major cities. It was then that Chiang ordered the massacre of thousands of members of the Chinese Communist Party, then a faction within the KMT. An infuriated Soviet Union cut their ties with the KMT, leaving Chiang without a vital military partner.

The Northern Expedition was Chiang’s route to power; having got there with military strength, he now relied on it to remain there. But if he was to protect his position and unify China, Chiang would need another tutor.

THE GERMANS ARRIVE

The collapse of Imperial Germany in WWI a decade before had left thousands of skilled officers out of work. Surely, thought Zhu Jiahua, a German-trained scientist in Chiang’s civil administration, these men could help the KMT unite China. So in 1926, he began by contacting Colonel Max Bauer, the first in a string of German officers who would remould China’s defences.

Bauer was an advocate of total war – the focusing of a nation’s full resources on war, ideally under authoritarian rule, with a professional military backed by a robust industrial base. Each of these points appealed to Chiang for several reasons: the first emphasised Chinese unity, the second reflected the Nationalist belief that China must be ruled strictly until it was ready for democracy, and the third would make it self-sufficient in both resources and defence.

Before dying of smallpox after less than a year in China, Bauer promoted industrialisation, the development of air power, and Nationalist propaganda. He also convinced Chiang to move Whampoa (renamed Central) Military Academy to Nanjing, the new capital, and to establish a military intelligence service, formal training programs, and a foreign publicity initiative.

Bauer and his successors were men who’d been intimately involved in rebuilding the shattered German military into an agile, effective force which could, and would, be expanded into the Wehrmacht when the Nazis came to power. They proposed to do the same for China.

A DIRE SITUATION

From 1926 to 1937, German experts analysed every facet of China’s industry, economy, governance, and military, while warning Chiang that much of the reforms needed to expand were out of his reach. Between economic underdevelopment and foreign debt, the country’s finances were in tatters. Chiang would not be able to afford a cutting-edge German-style military unless years of development and reform were undertaken.

But there were two advantages in Chiang’s favour: first, China had vast natural resources, including tungsten and antimony, two metals vital to industry. He also secured the services of a military A-lister in Hans von Seeckt, architect of Germany’s postwar military. A deal was struck: Chinese tungsten for German guns and equipment, with advisers to remodel the Chinese military along German lines.

von Seeckt proposed that the KMT disband ex-warlord units, raise 60 “New Divisions” from scratch along German lines, and Germanise a further 60 into “Reformed Divisions.” Officers would be assigned randomly and conscription would replace ad hoc recruitment, forging a force which would be loyal to the state alone.

By 1930, two training divisions existed, which would later be converted to full-time professional units. The 87th and 88th Divisions, both of which underwent extensive training, cooperated in the first-ever modern military exercises in China, and which were put to the test on numerous occasions against the warlords Feng Yuxiang and Yan Xishan in 1930, the Japanese in 1932, the rebellious 19th Route Army in Fujian in 1933, and the Chinese Red Army in 1934. As the decade drew to a close, these two divisions were the most experienced, well-trained, and relied-upon units in Chiang’s National Revolutionary Army.

But those qualities were yet to face their greatest test. On the night of 7th July, 1937, Japanese and Chinese troops fired at each other at the Marco Polo Bridge in Beijing. It’s been suggested that the incident was staged, but whatever the truth, Japanese rulers hungry for conquest had their pretext for war. Their first target was Shanghai.

THE TEST

Immediately after Japan’s declaration of war, all eyes turned to Shanghai, China’s largest, wealthiest, and most developed city. Shanghai was also critical to the Nationalists’ economic plans and home to thousands of foreigners from Europe, America, and Asia. If Japanese forces could take it, they could strangle access to China’s interior and split the country in two.

It was an impossible position for Chiang: his only chance was to strike quickly and drive them off. Failing that, his army would put up such a spectacular fight, in full view of the world’s representatives, that Western nations would rally to his aid. As he saw it, only his finest troops were up to this daunting task. Alexander von Falkenhausen, von Seeckt’s successor, begged Chiang not to throw away the cream of his army. But the Generalissimo was fighting a different war – a diplomatic war.

Over the course of three months of savage urban fighting, China would pour 700,000 men into Shanghai. Japanese troops, expecting frail warlord units, received a nasty shock when they discovered that they were up against German-trained soldiers more than capable of holding their own.

The 36th, 87th, and 88th Divisions dug in in Zhabei, in the north of the city. They lacked heavy weapons, tanks, air support, and radios. What equipment they did have was of high quality: Chinese-made Mauser rifles, German combat helmets and hand grenades, mortars, Maxim machine guns, and a small number of high-quality artillery pieces.

By October, the 88th Division had become known to the Japanese as “the hateful enemy of Zhabei.” But this reputation came at a gruesome cost. After three months of constant fighting, only 20-30% of the men in the vaunted Germanised divisions were veterans. The rest were raw recruits sent in as hasty replacements.

Moreover, the German divisions weren’t perfect: a report on the first two weeks of fighting revealed many flaws in reconnaissance, combined arms tactics, and equipment. In the face of well-equipped, highly trained, and professionally led Japanese forces, even the most motivated and experienced Chinese troops could not hold out. Even Chiang himself felt that it would take three Chinese divisions to equal one Japanese division in battle.

“The whole Shanghai front,” noted Chiang, “is collapsing, but we must resist Japan to the bitter end and not turn our backs on our original resolve.” The city couldn’t be saved. But the Nine-Power Conference, a meeting of the nations which held a stake in Shanghai, was convening to discuss ways of ending the burgeoning war. If even a token resistance held out in Shanghai, it would strengthen Chiang’s negotiating position and – maybe – convince the West of China’s resolve.

The task would fall to a single understrength battalion of the 524th Regiment, 88th Division. Colonel Xie Jinyuan, a Whampoa-trained officer, commanding 450 men, fortified Sihang (“Four Banks,” for the banks which funded its construction) Warehouse, a heavy concrete structure perfect for a defensive rearguard position. Over the course of six days, Xie’s men held off a Japanese force of twice their number.

The attackers prevailed after a week, capturing the “800 Heroes” (their true numbers are uncertain). In the Battle of Shanghai, as many as 225,000 Chinese soldiers had lost their lives. The finest divisions in the NRA had been gutted.

But the Defense of Sihang Warehouse, the final demonstration of what they’d learned, had given the survivors time to escape and regroup. Chiang and the Nanjing government retreated to the inland city of Chongqing, where they would remain until 1946. The Nine-Power Conference fizzled out without Japanese cooperation. But Chiang’s divisions had nevertheless inspired China to fight back and impressed the world with the country’s determination.

THE REAL SUCCESS OF SINO-GERMAN FRIENDSHIP

The reforms begun by von Seeckt and von Falkenhausen were too late to save China from a decade-long war in which over 15 million lives were lost or taken. When Nazi Germany transferred its friendship to Japan, the German military advisers reluctantly returned home. Chiang considered von Falkenhausen a friend for the rest of his life.

After Shanghai, those few divisions which had been the first steps in their reforms were almost obliterated. The 87th, 88th, and 36th Divisions would all survive, some going on to serve in Burma under the command of Joseph Stilwell. Even if they’d long lost their German character by then, they were still regarded as elite units by Nationalist commanders.

The German mission had other, more far-reaching effects. The emphasis on industry and economy was taken to heart by the KMT, who set up the National Resources Council to exploit resources and expand China’s military industry. By the end of the war, the NRC commanded a workforce of hundreds of thousands. Through it, the KMT controlled mining and metal production, the machinery industry, fuel production, and the chemical sector.

Like the German-trained divisions, it came into being too late to form a true military industry for China, but it did produce enough of the critical resources the NRA would need to buy time. Just as the men sacrificed at Shanghai held off the attack, the NRC kept Chinese troops supplied long enough for a far more effective patron, the United States, to enter the fight.

China would emerge, battered but victorious, from the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1945. But Chiang had never managed to overcome the same problems identified by his German advisers a decade before. Nationalist military strength was too divided by warlord-style factionalism, and too ready to garrison static positions. This left them vulnerable to a far more mobile enemy, Mao Zedong’s Communists, who would topple the KMT in 1949 and drive its remnants onto Taiwan. But on both sides of the Taiwan Strait today, the legacy of the German-trained divisions lives on in the mythical status of the 800 Heroes.

Articles you may also like

Weekly History Quiz No.228

1. Which is the only walled city in North America?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

D-Day succeeded thanks to an ingenious design called the Mulberry Harbours

Reading time: 4 minutes

When Allied troops stormed the beaches at Normandy, France on June 6, 1944 – a bold invasion of Nazi-held territory that helped tip the balance of World War II – they were using a remarkable and entirely untested technology: artificial ports.

To stage what was then the largest seaborne assault in history, the American, British and Canadian armies needed to get at least 150,000 soldiers, military personnel and all their equipment ashore on day one of the invasion.

General History Quiz 171

1. When was the US White House burned by British forces?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.