Reading time: 5 minutes

Nationalism is resurging across Europe, and with it has come increasing attention on the vulnerable outer edges of nations: borders, frontiers, and other marginal zones. Today, some of the frontiers of the Roman Empire are now national boundaries, but in antiquity these spaces functioned very differently from how we understand borders today.

I am part of a large team currently excavating one of these sites, a fort called Halmyris in modern-day Romania. Halmyris was the easternmost fort on the Danube frontier of the Roman Empire, and the first port of call for anyone sailing up the Danube river from the Black Sea. Rather than a place of exclusion and defence, our digs are uncovering how the border of the Roman Empire was also home to sites of cross-cultural encounter and exchange.

By Emily Hanscam, Durham University

The Roman frontier on the lower Danube was one of the most heavily fortified frontiers in the Roman Empire, but it was designed as a permeable boundary, allowing the movement and peaceful interactions of different cultural groups. The frontier was defensive, with hundreds of military installations from legionary fortresses, auxiliary forts and watchtowers, but it also supported trade and large civilian settlements.

This was the region where migratory tribes like the Goths first encountered the Roman Empire, followed by the Huns, Avars, Slavs and Bulgars from the fourth to seventh centuries during the late stages of the empire. This was the primary reason for the density of fortifications on the lower Danube, but it also makes it a region which hosted one of the greatest sustained cross-cultural encounters, occurring at a time of great change. Rome was in decline, and the peoples entering the west via the lower Danube would build the medieval feudal kingdoms of Hungary and Bulgaria among others.

We know about what happened when this permeable frontier failed – as it did in 378AD at the Battle of Adrianople. The Emperor Valens was killed by the Goths, a group he had previously granted asylum to when they asked to move south of the Danube en masse.

But we need to learn more about how it succeeded – who populated the civilian settlements around the forts, and why this region in particular seems to have been favoured for cross-border migration during the Late Roman Empire.

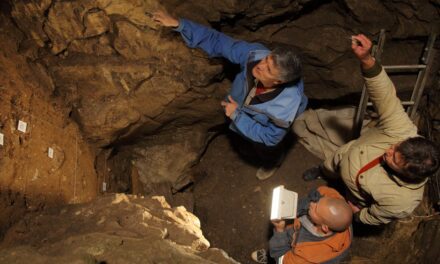

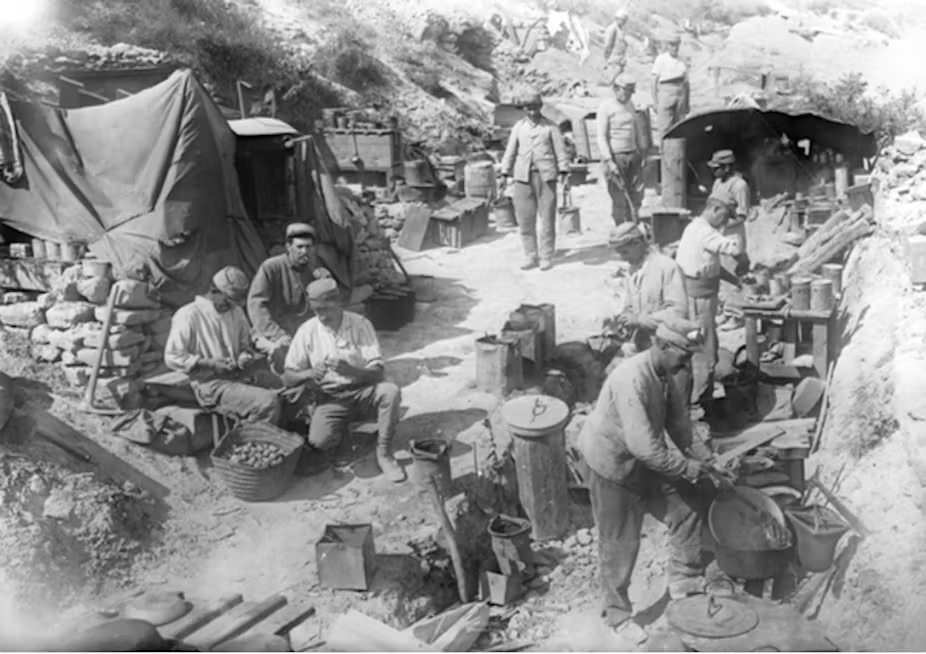

Excavating Halmyris

I have spent six seasons working as an archaeologist at Halmyris. In the past few years, over a hundred students and volunteers from around the world have helped excavate the fort. Since 2013 we have uncovered a number of military structures such as barracks, weapons storerooms, and a bastion with a platform for artillery, most dating between the fourth and sixth centuries. This shows us that Halmyris continued to be important for the defence of the region throughout the Late Roman and Early Byzantine periods, at a time when other forts in the region shifted into fortified civilian settlements.

Halmyris has an unexcavated civilian settlement stretching for acres around the fort, which we began surveying in 2016 and hope to excavate in forthcoming seasons. We might find traces of the migratory people here. Previously we have found a stray Slavic-style pot fragment on the fort, evidence of the sixth and seventh centuries but nothing substantial.

Religious tensions

In 2001, the archaeologist Mihail Zahariade discovered the remains of early Christian martyrs Astion and Epictet in a crypt at Halmyris. These men had been executed by the Romans in 290AD and later reburied in the crypt beneath the basilica built on the orders of Constantine the Great in the early fourth century. They may be the earliest “homegrown” saints of the Romanian Orthodox Church, and provide proof of the early spread of Christianity in the region.

When they were discovered, the church declared Halmyris a holy site, and limited further archaeological work there. The Romanian government opposed this, and instead today only the basilica is officially designated a holy site and will not be excavated further. The crypt is badly in need of preservation, but the lack of funds and competing interests have so far prevented us from conserving the monument.

We joke on the site that whatever we uncover, we hope it’s not another basilica. Humour aside, it is a shame that something so important for Romanian religious heritage cannot be better preserved and valued for years to come as part of the living history of Halmyris, a site situated within a fascinating modern frontier landscape, poised on the margins of the EU.

Frontiers and borders will be increasingly important in the 21st century. Romania itself is a border nation of the EU that may yet face the pressures of significant immigration like Greece and Hungary. How we understand and choose to engage with the frontiers of the past is crucial to how we relate to modern issues of migration. I hope that through projects like those at Halmyris, we can highlight the potential of frontiers to bring people together rather than focus on building new walls, or passing new legislation to keep migrants out.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

Podcasts about archaeology and nationalism

Articles you may also like:

Why we don’t hear about the 10,000 French deaths at Gallipoli

Reading time: 6 minutes

With almost the same number of soldiers as the Anzacs – 79,000 – and similar death rates – close on 10,000 – French participation in the Gallipoli campaign could not occupy a more different place in national memory. What became a foundation myth in Australia as it also did in the Turkish Republic after 1923 was eventually forgotten in France.

FORGOTTEN ANZACS: THE CAMPAIGN IN GREECE, 1941 – BOOK REVIEW

Reading time: 2 minutes

A look at the book Forgotten Anzacs: The Campaign in Greece, 1941 – Revised Edition, by Peter Ewer: the largely unknown story of an Anzac force which fought in Greece during World War II.

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.