The Militia and the AIF

Reading time: 10 minutes

Imagine you’re a young 20 year old bloke. You’ve just struggled across sixty miles of some of the toughest terrain on earth. You’ve had bugger all training, your weapons are obsolete because you’re “just Militia” and all the best stuff is being used by the Second AIF in North Africa. But here you are on the pointy end of the attempt to defend Australia from direct attack. In front of you, heading your way, is the Japanese Army which has just swept through Malaya, captured Singapore, bungled General MacArthur out of the Philippines and have not known defeat so far in this war.

It’s all down to you and your mates, other young blokes from down Victoria way, with just a smattering of experienced older soldiers. How are you feeling about now? Not real flash I bet.

At the outbreak of war in 1939, Australia raised an all-volunteer force of troops for deployment overseas alongside British and Commonwealth Forces against Germany. As in 1914 many young Australians rushed forward to join this new force, to show they were worthy to stand alongside their ANZAC (Australian and New Zealand Army Corps) fathers, or for the sense of adventure, or simply because it paid well and was maybe even an escape from a less than exciting life.

But for some, running off and fighting overseas didn’t seem like such a great idea. It certainly hadn’t done many favours for the original ANZACs, many of whom were still suffering from their service. But these young fellas still felt a sense of duty and a desire to do their bit should Australia be threatened. So many joined the militia units spread across the country.

As you would expect there was a bit of antagonism between the AIF and the militia. The militia could not be compelled to fight overseas, which led the AIF troops to give them titles such as chocolate soldiers (or chocos for short), insinuating they’d melt when it gets too hot, or koalas – not to be exported or shot at.

Enter Japan

So for a while, as far as the militia units were concerned, everything was going well. The war was all the way over there and Australia wasn’t directly threatened in any way. But Japan was increasingly developing into a threat and the Government and military hob nobs suddenly started feeling a little insecure about the lack of forward defence of Australia. It was decided that a garrison force should be stationed in New Guinea to at least provide some sort of token attempt at defence.

But who to send? Couldn’t send the AIF. They were busy elsewhere. So who else? Ahh the Militia. “But”, I hear you ask, “I thought you said they couldn’t be compelled to fight overseas.” And you’d be right. But as part of the spoils of WW1, Australia was granted certain rights over the former German territory of New Guinea. This worked out well for the aforementioned Government and military hob nobs, because that technically meant it was Australian soil and therefore the militia could be sent to defend it. The sneaky buggers.

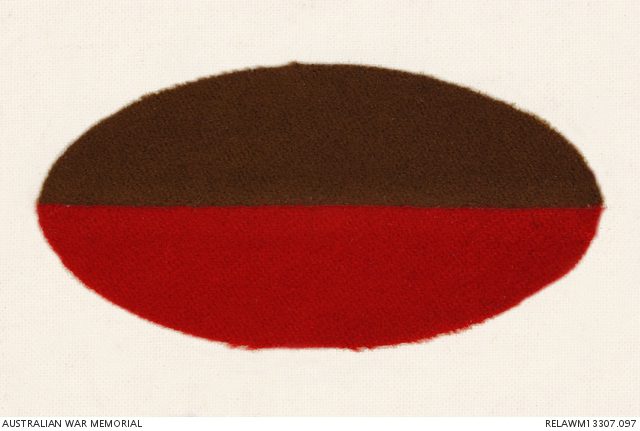

The vanguard of the militia, 200 soldiers from the 15th Battalion, landed in Port Moresby in mid-1940 and the 49th Battalion followed in March 1941, absorbing the original 200 men. The 53rd Battalion, and our lead protagonists, the 39th Battalion, arrived in January 1942, less than a month after Japan began a series of attacks across the Pacific and South-East Asia. Together they formed the 30th Brigade.

The 39th Militia Battalion was formed in Victoria in October to November 1941 from various local militia units. The difference between these two Battalions could not have been more striking. The junior and senior officers of the 39th were determined that their men would be as battle ready as they could be made. They were drilled regularly, given what weapons training could be arranged and the men grew to have confidence in themselves and their leaders.

The 53rd on the other hand had leaders who were content to have the troops digging holes, unloading ships and just being general labour around the Port. Their officers seemed to treat it all as a bit of a lark. When push came to shove the predictable result happened, the 53rd performed relatively poorly. But as Napoleon once said, there’s no such thing as bad troops only bad officers. So unlike some other commentators, I’m not going to bag the troops and will leave it at that.

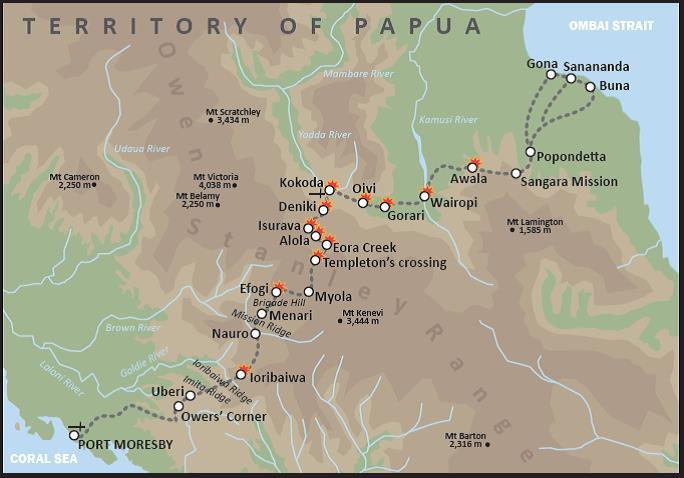

While stationed in Port Moresby the militia troops had their first taste of warfare when Japanese bombers began targeting the port facilities, in a softening up prior to a planned invasion. The landing was prevented by the Allied victory at the Battle of Coral Sea and a subsequent Japanese landing was thwarted at the Battle of Milne Bay. Being denied their first option, the Japanese decided an overland attack was required. The allied forces also foresaw this and decided to send a force to guard the airfield at a little plantation village known as Kokoda, about midway across the Owen Stanley Ranges.

With their only available choices being the 39th, 49th or the 53rd Battalion, the 39th got the nod. I’ve stumbled across a document titled Fighting in New Guinea – Narrative of the 39th which states:

“The 39 Bn had been in New Guinea about seven months. All ranks had trained hard in the same manner as other bns, had prepared and occupied beach posns and exercised constantly in patrol and movt. They had more than a nodding acquaintance with Jap bombs and had experienced the thrill of seeing Jap fighters crash in flames as a result of their machine gun fire.”

“All this had created an aggressive attitude in the minds of all ranks. Firstly they had become sufficiently familiar with the country to dominate their environment and feel more or less at home in the bush. Secondly they wanted to get the Jap on the end of their foresights. They wanted to meet him and beat him.”

Stirring stuff, but is probably more of an effort of a commander to talk up his troops than an accurate reflection of the feelings of the troops. First up, no one dominates the Owen Stanley Range. And although I have no doubt they were in an aggressive frame of mind and determined to do their best, I can’t imagine too many of them were as enthusiastic to meet the Japanese as is portrayed here. I shall return to this quote later in the article to hopefully explain what I think was going on when this was written. But for now – troops confident, happily going to meet the enemy.

The 39th was combined with the Papuan Infantry Battalion to form Maroubra Force. B Company of the 39th led the way into the mountains carrying pretty close to 20 kilos each of personal equipment, weapons and ammunition. 20 kilos doesn’t sound like too much, but after two days of carrying that weight up and down 1,000 feet ascents and descents, it became clear that if they were going to arrive at the destination in anything resembling fighting condition, then the load would need to be lightened. Native carriers took up the burden in what would become one of the enduring features of the New Guinea campaign – villagers working hand in hand with soldiers taking supplies up and eventually taking wounded back.

The First Battles

After six days struggling through the jungles and over the hills, the troops finally came out of the mountains and onto the plains with the forward-most elements reaching Awala. There they met up with a carrying party bringing in supplies which were landed at Buna shortly before the Japanese landed just to the North at Gona.

On 23 July, B Company, under the command of Captain Sam Templeton, met the Japanese for the first time. Knowing the Japanese would soon be heading their way in strength, B Company destroyed a bridge over the Kumusi River. They saw a patrol of roughly 50 enemy on the opposite bank and opened fire, killing a number of them and the survivors retreated.

It was a good start to proceedings but was to be short lived. Hundreds of Japanese marines soon began to cross the river, and the small band of Australians was never going to hold them off for long.

The first of many strategic withdrawals was made to a position at Oivi where Templeton set up an ambush. The Company managed to halt the Japanese advance throughout the afternoon, but by early evening it was clear the Japanese were working their way around the flanks and Captain Templeton took it upon himself to make his way back to Battalion HQ to ask for reinforcements. He didn’t make it.

For the remainder of the Company, it was obvious the position was about to be surrounded and they had to either get out or be annihilated. A native lad named Sanope led them down a small track and after a day and half they were able to re-join the main track near Denika.

39th Battalion at Kokoda

Meanwhile, with the little village of Kokoda and its airfield secure for the time being, a platoon of D Company was flown in along with the commander of the 39th, Lieutenant Colonel William Owen. Owen took command of about 80 men from B Company who had been left at the village and prepared to defend against the imminent Japanese assault. They set up their main defensive position on a spur line on the eastern side of the runway.

The Japanese attack came on the evening of 29 July. The initial assault came in during the late afternoon with trumpet calls and shouting as the Japanese soldiers surged towards the defences. After a brief, but violent encounter, sometimes hand-to-hand, the Japanese fell back.

Then, under the cover of darkness the main attack came in, with a quieter approach along the spur line. This would be the standard Japanese tactic throughout the following campaign. Launch a probing attack of sufficient size to oblige the defenders to open up with everything they have, determine the defensive layout and then send in the main attack while attempting encirclement.

The defenders resisted strongly with rifle and machine gun fire. A steady stream of grenades were hurled with accuracy towards the Japanese, with Colonel Owen adding his own throwing arm to the enterprise. The Japanese were temporarily halted but soon renewed their efforts. Again they were greeted with strong small arms fire and grenades. Colonel Owen’s luck though was about to run out.

While in the act of throwing a grenade the Colonel was shot in the forehead. He was taken back to the hut which was being used as a hospital and the seventy year old doctor, Doc Vernon did his best to save Owen, working under a light held by his assistant. But it was hopeless, and Colonel Owen died on the table.

Now this raises an interesting point. Owen was taken to a hut in the village where Doc Vernon had set up a makeshift hospital, basically in the middle of a battle zone. This seventy year old man was performing surgery while a battle raged a short distance away. That he could remain calm enough and steady enough to perform delicate operations is quite amazing.

By 01:00am, after eight hours of near continuous fighting it was obvious the defensive position of Kokoda was becoming untenable. The Japanese were working their way around the flanks and if they managed to reach the only track out of town, the garrison would be surrounded and destroyed. The order to withdraw to the next defensive position, a mile back along the track at Deniki, was given. A brief lull in the fighting ensued as the Japanese main force moved in to occupy the village.

But the battle for Kokoda was only just beginning. Read Part 2 of the 39th Battalion’s story.

Warwick O’Neill runs the fantastic Australian Military History Podcast. Check out his episodes covering all aspects of the Australian experience under arms.

Articles you may also like

Ruin Ridge – Podcast

During the 1st Battle of El Alamein the 9th Australian Division was tasked with the capture of Ruin Ridge. Despite heavy fighting during the opening stages they achieved some of their objectives, but their successes obliged General Rommel to divert large numbers of troops to contain the Australian advance. The fighting then became desperate, leading to heavy casualties and the near decimation of one battalion.

6th Australian Cavalry Reg in the Mediterranean, WWII – Video

The 6th Australian Cavalry Regiment were the first unit of the AIF to see action in the Western Desert in 1940. This is their story.

Remembering the Victory at Bardia

Just over 80 years ago, Australian forces fought their first major battle of World War II. Bardia, a small town on the coast of Libya, some 30 km from the Egyptian border, was an Italian stronghold. The Australian troops occupied Bardia, defeating the Italians in a little over 3 days. Australian veteran, Phillip Wortham, simply […]

This article is published with the permission of the author. If you would like to reproduce it, please get in touch via this form.