Part of the volunteer 2nd Australian Imperial Force (AIF) during World War II, the 2/3rd Battalion was formed on 3rd November 1939, drawing its men from a region in New South Wales known as “The Werriwa.” This area, rich in military heritage and tradition, spanned from Sydney to Bega in the south and westward to the Snowy Mountains, encapsulating Cooma, Canberra, Yass, and looping back through Goulburn and Liverpool. The battalion’s formation was part of Australia’s rapid military expansion in response to the global conflict that had erupted in September 1939.

By Roberto Golovic.

The battalion’s first commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Vivian England, was a seasoned veteran of the First World War and had continued his military service in the post-war period, commanding the 55th Battalion of the Militia. The 2/3rd Battalion adopted the unit colour patch of chocolate over green, a nod to the colours of the 3rd Battalion, which had served with distinction in the First World War.

After a brief training period in Liverpool and Ingleburn, the battalion marked its departure with a farewell march through Sydney, evoking memories of the first AIF’s departure for the First World War. The Sydney Morning Herald, reflecting on the march, noted the emotional impact on the city’s populace, drawing parallels to the sense of unity and purpose that had characterised the nation’s war effort a quarter-century earlier. The battalion then embarked for the Middle East in early 1940, aboard the transport Orcades, disembarking at El Kantara on the Suez Canal on 14th February 1940, then travelling to their camp at Julis in Palestine, where they undertook further training, preparing for the rigours of combat in the North African desert.

Their first engagement came at Bardia in January 1941, a major Italian military outpost in Libya. The successful assault on Bardia by the 16th Brigade, which included the 2/3rd Battalion, marked the first significant engagement of Australian troops in the Second World War. The operation showcased the effectiveness of Australian infantry and set the stage for subsequent actions in the North African campaign, including the capture of Tobruk, where the battalion again played a crucial role. These early victories were vital in boosting the morale of the Allied forces and demonstrated the skill and bravery of Australian troops in the face of entrenched enemy positions.

Following their success in North Africa, the battalion’s next major engagement was in Greece in 1941. Deployed as part of an Allied effort to defend Greece against German invasion, the battalion faced a well-prepared and numerically superior enemy. The battalion engaged in a critical delaying action at Tempe Gorge, also known as Pinios Gorge. They fought a series of rearguard actions down the length of Greece before being withdrawn. While the majority of the 2/3rd Battalion was successfully evacuated to Egypt, 141 men were onboard the transport ship Costa Rica, which was sunk, and they were taken to the island of Crete instead. These men fought in a composite Battalion, with the majority eventually reaching Egypt after the fall of Crete.

The battalion’s experiences in Greece and Crete were followed by their involvement in the Syria-Lebanon Campaign against Vichy French forces in mid-1941. This campaign was a critical effort to secure the eastern Mediterranean and prevent the Axis from exploiting Vichy French territories. Despite being under strength, the 2/3rd Battalion played a significant role in the Allied victory, demonstrating adaptability and courage in a complex and challenging operational environment.

In 1942, as the war in the Pacific intensified, the battalion was redeployed to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) to prepare for a possible Japanese attack. The battalion’s time in Ceylon was marked by intensive training and preparations, which honed the skills that would be crucial in the coming campaigns in the Pacific.

The battalion’s return to the Pacific in 1942 brought them to the front lines of the conflict against Japan. Their involvement in the Kokoda Track campaign and subsequent operations in New Guinea were among the most challenging and pivotal of the war. The 2/3rd Battalion, along with other units of the 6th Division, faced grueling conditions and fierce resistance as they fought to push back the Japanese advance. These campaigns were characterised by difficult jungle warfare, where determination, endurance, and the ability to adapt to challenging conditions were essential for success.

The battalion’s final major campaign of the war was in Aitape-Wewak in 1944-1945, where they were tasked with clearing Japanese forces from the region. This campaign was marked by difficult terrain, determined enemy resistance, and the challenges of conducting operations in a disease-ridden environment.

Following the end of hostilities, the battalion undertook occupation duties before being repatriated to Australia, where it was disbanded in February 1946. Throughout its service, the 2/3rd Battalion exemplified the qualities of courage, resilience, and mateship that have come to define the Australian military tradition. Its members, drawn from communities across New South Wales, served with distinction in some of the Second World War’s most challenging campaigns, earning a place of honor in Australia’s military history.

The 2/3rd Battalion had fought all the major Axis powers: the Italians, Germans, Vichy French and Japanese. Alongside the Australian 2/5th Battalion, they were the only Allied troops able to make this claim. During its service a total of 3,303 men served with the 2/3rd Battalion of whom 203 were killed and 432 wounded. Members of the 2/3rd received four Distinguished Service Orders, 16 Military Crosses, 12 Distinguished Conduct Medals, 30 Military Medals, two British Empire Medals and 73 Mentions in Despatches.

Men of the 2/3rd Australian Infantry Battalion

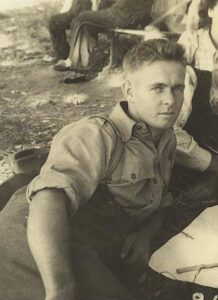

Private Bernard “Dusty” Kuschert

Bernard “Dusty” Kuschert was a Greek campaign veteran from Goulburn. He was born in 1917, as the fifth child, and had enlisted in the AIF from the very onset of the war. He boarded the Orcades on the 9th of January 1940, with the rest of the 2/3 Australian Infantry Battalion. He remembered his ship being part of a 15-vessel convoy that left Australia on that day. The ships first went to Colombo and then to the Red Sea. Dusty disembarked in El Kantara, midway up the Suez Canal, while New Zealanders went to Egypt, Australians went to Palestine.

News of Italy entering the war found him at Camp Julis. A few months later, Dusty had his first combat experience, first at Bardia and then at Tobruk. He described it as a frightening but exhilarating experience.

In mid-March 1941, Dusty and his battalion arrived in Greece via HMS Gloucester. As in Libya, Dusty’s role in the army was that of an officer’s batman, a role he described as follows: “If you’re in camp, you’re supposed to have the officer’s shaving gear ready and have his uniforms looked after, and stuff like that. A general handyman. But Len Herwig was unlucky because I think he was the untidiest-looking officer of all because I was his batman. And I was with him all the time.” In Greece, he followed the above-mentioned Len Herwig, who was a quartermaster, so it meant that he spent most of his time in a truck as they were heading north of Athens to Larissa. In April, Yugoslavia had succumbed to German occupation and ANZAC forces were proceeding towards the Yugoslav border to prevent the same from happening to Greece.

Dusty remembers huge convoys of ANZAC troops round the foot of Mount Olympus, both on foot and on carriers, going through two-foot deep snow into the Tempe Gorge. He did not see much of the battle in the gorge when the order to retreat came. It was a dangerous journey through the Greek countryside, constantly under attack from the Luftwaffe. The retreat was chaotic, and there was no unit cohesion, and regular attacks by low flying German aircraft. One of Dusty’s mates managed to shoot down a German airplane with a lucky burst from his Bren gun – a small victory amid what must have seemed like a disaster at the time. A week later, they reached the designated evacuation spot:

“I think it was about Anzac Day, it might have been the twenty-fourth or twenty-fifth we were coming through Athens in a hurry. And we were supposed to get on board ships at Argos just over the Corinth Canal. But when we got there, the two ships were blazing in the harbor. And so we carried on down to Kalamata right. One of the bays right at the foot. We were there in olive groves near the beach. And the women of the village, they were really peasant women. They were very kind to us, fed us and stuff like that. And even gave us a shampoo to some of us. There was no mucking around or anything like that. They were just wonderful friendly people.”

Dusty boarded HMS Hero and went straight to Alexandria, luckily avoiding being part of yet another ill-fated encounter with the Germans on Crete: “Oh, we were a bit down in the mouth, but we were fortunate, as I say, that we came out with better than half a battalion strength. Whereas the 2/1st Battalion, as I say, was down, about thirty men. Big difference, isn’t it?”

What Dusty found most inspirational in his experience was the camaraderie and exceptional leadership of some officers he encountered during his time in the service: “We were fortunate to have Colonel England as our commanding officer. “Black Panther” we called him. We became his cubs. And when we came down from Libya, he was transferred and became a brigadier, and they put him in charge of the Infantry Training Battalions. Much against his will… When we landed back in Julis after Greece, it was nighttime in the tents at Julis. And the brigadier came round to every tent, finding out what happened to who and what. He knew us all, a marvelous man. And I think that’s what made our battalion so good. Because we all wanted him to be proud of us. And I don’t think we let him down.”

After the Greek campaign, Dusty fought in Syria and New Guinea, not as a batman anymore but as a rifleman. He served until the end of the war and was very modest about his contribution: “I didn’t win any gongs, any medals I wear, I only earned them. We had quite a few chaps who were decorated. And I didn’t decry ‘em a bit. I would’ve liked to got one, but I didn’t.”

During a run-in with malaria in the Pacific, Dusty met his future wife. They got married immediately after he was discharged. Their first child was unfortunately stillborn, but in 1948 they had a son, Bruce. Dusty’s first captain from the war became Bruce’s godfather. In the ‘50s, Dusty moved to New Zealand but took special care to attend ANZAC day reunions in Sydney.

Lance Corporal Neville Blundell

Neville Blundell was a soldier in the 2/3rd Australian Infantry Battalion, awarded the Military Medal for ‘conspicuous bravery and devotion at Bardia on 3rd January 1941’, and a veteran of the Libyan, Greek, Syrian, and Papuan campaigns. He was living in Tempe, in Sydney’s Inner West and working in steel mills when the war started. That night when he heard Prime Minister Robert Menzies announce Australia would join the war, he “was wondering why they didn’t challenge the Germans in the first place after so many years.” Neville remembered: “I was quite happy that they took it on, in a sense. We were pretty well informed about that. We used to know the names of all the characters, even the lesser people. We weren’t living in the dark, in a sense.” Neville enlisted the very next day.

Neville married his wife Mavis on the 2nd of January. On the 4th of January, he marched through Sydney with his unit, and on the 10th of January, they sailed out. Like his mates, Neville was unsure of their destination, and everyone speculated it could be England, but one night at midnight they disembarked at El Kantara in the Suez Canal. In Egypt, Neville applied to be trained as a runner, a soldier who carried messages between units and undertook similar tasks.

His first taste of battle came at Bardia. Although a tremendous success for the ANZAC forces, it did come at a price. Neville described an episode of gallows humor soldiers would resort to in order to calm their nerves: “One of the company commanders was sent a message from another company about one of the young officers who had been hit directly by a shell on the leg. He was seriously injured of course and was taken back to where we were. We were doing this bit of laughing and he got very annoyed. He said, ‘If you’d seen what I had seen you wouldn’t be laughing.’ Reggie Burns, who was the sort of ringleader, said, ‘What do you want us to do, cry?’”

Neville distinguished himself in this battle through an attack on an enemy fortified position and would later be decorated for his actions. He described the situation: “As I was going up the hill, I saw one of these fellas get hit with one of these Italian grenades and he was hopping across our front. Then he sat on a rock which was about thirty yards from the sanger. I worked my way across to him and said, ‘Are you all right?’ He said, ‘Yes.’ He said, ‘Go up there and kill the bastards.’” Neville went up, scaled the walls, but killed no one as the Italians were in shock to see him suddenly up there pointing the gun at them.

After the initial battle of Tobruk, the 2/3rd Battalion went to Greece aboard HMAS Gloucester. Neville remembered the cruise lasting less than a day, but the ship was constantly under attack by the Italian air force. His unit moved from Athens to Daphni and after a week or so to Larisa, in the middle of Greece. Neville described the Greek population as very friendly to Australian troops, but Larisa as a town that had suffered much damage both from an earthquake and air raids. During the battle of Pinios Gorge, Neville recalled groups of 30 Stuka airplanes at a time attacking ANZAC positions. Air superiority was one of the major reasons why the Germans could not be defeated in this engagement, and a retreat was eventually announced.

“I was with a group who got out early. We were on a truck, but a lot of people couldn’t get on trucks and they were just walking.” The retreat was not unimpeded, and their truck was subject to regular aerial attacks. “There were a couple of blokes standing by the back of the cabin with the cover pulled back so we could see what was coming. When the planes approached, we used to bang on the lid, and they’d pull up. Everyone would dive out and get as far away as they could in the time they had. Two blokes got wounded during one attack. We picked up a New Zealander when we started off. He’d driven over a bomb, which had exploded under him. It had killed his driver,” Neville recalled.

Eventually, they managed to reach Kalamata, at the very south of mainland Greece, and evacuate via destroyer. According to Neville, they managed to avoid the fiasco at Crete through the captain’s decision to sail straight to Alexandria, for one reason or another. Back in the relative safety of the base, Neville received his first medal, but also his first wound of the war: “I got a decoration and because we hadn’t seen each other, they kept buying me beers. I couldn’t really drink, so I got in a limp condition, and one of my mates was taking me home. We went across a wadi. A wadi is a little creek. It was about six foot deep. I got out of it, but I must have stumbled on some loose stones and bundled my leg up like that. In the morning, I couldn’t walk.”

After the Greek campaign, Neville distinguished himself in both the Syrian and Papuan campaigns. Before sailing to New Guinea, he went home for a short leave and thus had a five-month-old daughter waiting for him when he came back from the war. He was always proud of his service and glad to participate in ANZAC Day parades whenever he could.

Private Frederick ‘Mack’ Megahey

Frederick Megahey was born in Ireland in 1918. His father, a policeman in Ireland, had served with many Australians during the Great War, so when a Commonwealth-funded migration opportunity came about in 1929, he took it. Ten years later, Mack had signed up to fight for his new country in yet another world war.

“I enlisted, I think, before we even knew who the enemy was, because I enlisted on the 26th of October ‘39. We were the first contingent to leave the Bega district. There were 26 of us. ‘Bega to Berlin’ is the group.”

In January 1940, a mere week after he got married, Mack had sailed aboard SS Orcades towards the Middle East. He would not see his wife for two and a half years. 2/3rd Battalion disembarked at Al Qantarah in the Suez Canal and went via buses up to Palestine to Camp Julis. After Italy entered the war, Mack remembered moving with his unit to Camp Mena, near the pyramids. At Bardia, Mack experienced combat for the first time. He remembered some Italian units being strong and fighting bravely, while others simply surrendered without fighting.

“They built the camp, the Italians, and they were going to put us in it. They were going to beat us and they were going to put us, but we put them in it, in the camp that they built. So, just after the attack on Bardia, we took, I think it was, this is pretty authentic, I think it was 20,000 prisoners there in Bardia. We put them into this enclosure they had made for us.”

After Tobruk, Mack and his unit went to Greece aboard SS Cameronia. After a brief period at the camp near Athens, Germany had entered the war with Greece, and ANZAC forces were moving north to prevent their entry into Greece from Yugoslavia.

“I, with a group, moved up to a place near, never got quite there, Larissa. The Germans almost flattened Larissa. They absolutely flattened it so we didn’t go any further. We came back to the airport at Athens, and most of the ones of that group that came to the airport were taken prisoner. I’d say two-thirds of them were taken prisoner when the Germans surrounded the airport.” Mack remembered. He was not with those captured, however. With a few of his mates, he managed to escape into the night. As soon as they reached the outskirts of Athens, they got lost and separated in the streets.

Scared and lost, Mack wandered about until he was lucky enough to come across a truck carrying some Australians and New Zealanders. They reached the wharfs of Port Piraeus at one o’clock in the morning only to find about 50 people there with no idea what to do. Eventually, the steamer MV Julia came along and took the men aboard. Unfortunately, it was a very slow ship, moving no faster than 4-5 knots, so it did not get far before dawn.

Mack described the situation: “Bear in mind there were about 20 ships sunk during the evacuation of Greece of all shapes and sizes. A lot of them had escorts and had anti-aircraft guns. We had nothing. We had no escort, we had no guns. About 8 or 9 o’clock there was a group of German Stukas, because Germany had complete control of the air. They had complete control. These Stukas came over and they made an awful noise as they screamed down. They’ve got these whatever it is. The noise was worse than the peril. Shocking.”

The ship suffered much damage from the bombs, but none of it catastrophic as there were no direct hits.

“Then they came back again after they’d used all their bombs and they machine-gunned the ship from one end to the other. The funnel looked like a flour sifter with the bloody bullet holes. I don’t know how many were wounded. I just recall one man there who got a bullet through his wristwatch and it had put the watch into his arm. Of course, there wasn’t any medical aid there. It took us about the best part of three days to get from Greece to Crete.”

On 5th May 1941, Mack was on Crete. He remembers it was one of the happiest feelings in his life, getting away from such danger unscathed. He was among those who were given rifles; those without them were evacuated early, while the rest were left there to face off numerically superior and better-armed German paratroopers. Mack remembers shooting a few German paratroopers on the first day of the invasion, but most of the fighting was spent hiding behind the rocks. They did not have a full unit and were ill-equipped for what they were facing.

Mack described the chaos that ensued after the defeat at Crete: “I got down to the water’s edge with a few others, and some provos (Provosts – Military Police) there said, ‘You can’t, only Kiwis (New Zealanders) are getting on this ship.’ I happened to have a Kiwi jacket on me that I picked up somewhere. I said, ‘What do you think I am?’ He said, ‘Get on.’ So I got away. A lot of people were taken prisoner there, including my brother. One of my brothers, the one that was in the 6th Division with me, he got taken there but escaped. He escaped.”

Of the entire Greek ordeal, Mack had the following to say: “Sending us to Greece was mission impossible. There was no way in the world that we could have won in Greece. We had no air force, we didn’t have enough equipment, we didn’t have the numbers. There was no way we could win it. We were there for a few weeks, lost, hundreds and hundreds of men were taken prisoner and killed, and in Crete, we never had a chance from the day we stepped in there. And Sir Thomas Blamey, the Australian commander, was against it. He voiced his opposition to it. But he was overruled.”

Mack eventually reached Alexandria, but he had serious medical issues with his eyes, so he ended up in a hospital and in 1943 he returned home. He was very proud of his service and thought of rejoining the army during the Korean war but was prevented by his medical issues.

Sergeant William ‘Bill’ Jenkins

William Jenkins was born in Sydney as the seventh child. His oldest brother was 20 years older and a veteran of the First World War. When the second war started, Bill was working a night shift at the glassworks and decided to enlist first thing in the morning. He went to Victoria Barracks where quite a few people waited to join up but were met with disappointment as the army told them they could not sign up there. A few days later, Bill, with two of his brothers and a couple of mates, went to Lakemba drill hall and enlisted.

In November 1940, Bill was in the Middle East with his battalion. At Bardia, he was a runner for the regimental sergeant major but did not see much action. Things changed at Tobruk in January 1941 when a platoon from Bill’s 2/3rd Battalion was pinned down by Italian fire.

“We got up to the place where the machine gun fire was coming from and we surrounded it and they were still firing, but if you can imagine they were down behind the bunker and put the gun over the top. You couldn’t see them but they were just reaching up and firing over the… and they couldn’t see where they were firing and the bullets were going up in the air so we threw grenades in until they decided to throw it in and that was the end of the day. The whole thing collapsed and we were allowed to move on, stay there rather which we did, we moved down to Tobruk itself into the town, and the next day we went swimming in the Mediterranean so it was a good war for a while.” Bill remembered.

After Tobruk, the 6th division, including Bill’s 2/3rd Battalion, was sent to Alexandria. There he boarded HMS Gloucester and sailed in an unknown direction, but Bill and his mates speculated it could be Malta or Greece. It turned out it was a good guess since 19 hours later they were in Piraeus, a port near Athens. Although brief, the cruise was not without its perils: “We were bombed by Italian planes on the way across, but they were so high, their aim was bad, so we were quite safe. In fact, the ship’s chaplain was giving a description of the raid over the intercom on the ship. ‘Flying over at about thirty thousand feet and they’ve let a couple go and they’ve landed astern’.”

Bill remembered being welcomed by the people of Greece, “mostly ladies and children ’cause the men were away fighting”, while they were marching shoulder to shoulder, as the first allied combat troops to reach this country. Troops were stationed at Daphne before moving “into the centre of Greece, the town called Larisa, which suffered earthquakes not very long before and then the Italians bombed it, so it had a pretty rough time.” Afterwards, the 2/3rd Battalion moved to Volos on the eastern coast of Greece. Here they got the news of Yugoslavia being defeated so they moved up north, to the Veria Pass, overlooking the Greek-Yugoslav border. However, “Germans being what they were they didn’t come that way, they came another way to outflank us, so we had to withdraw across the Aliakmon River. We had to ’cause the silly engineers blew the bridge across the Aliakmon River to Elasson and we had to march out over the mountains, over the side of Mount Olympus, a good ninety miles over very rough country because they couldn’t get us out any other way, but we eventually did and got onto trucks on the other side.”

Trucks gave them much-needed mobility, but they were not out of danger by any stretch of imagination. The convoys were bombed all the way to Larisa. From here the battalion moved up the Pinios Gorge where ANZAC troops had to hold off Germans for 24 hours. Bill remembers that it was 36 hours before they were given an order to pull back. Some units were in a position that was untenable, and many were taken prisoner. The rest withdrew across the Corinthian Canal and down the Peloponnese.

After reaching the very tip of the peninsula, Bill, a lance corporal at the time, was ordered to lead a standing patrol at the edge of the town, while the rest of the troops were evacuating or rendering equipment unusable to the invaders. Bill described the situation: “So we stuck there all day then about midnight, a fellow came up on a motorbike and said we’d be relieved and we were to go straight down to the wharf area, the harbour, and having come from there we knew where to go and as we started to go down a little old lady came out of an old cottage and she had a tray on which there were little glasses and there was ouzo, which is a Greek national drink, and some wine, and little bits of cakes, sort of cake or bread and she was weeping. They knew we had to get out because the Greek government had surrendered, signed an armistice.”

They boarded HMS Hero and were taken to a ship called Dilwarra. This vessel was continually attacked by Stukas, Bill remembered, and one of the bombs exploded so near the propeller that the explosion had bent it and slowed the ship significantly. Two ships were less fortunate and sunk, while the surviving passengers were taken to Crete to once again face the Germans. Despite all the attacks, Bill arrived safely in Alexandria: “apparently I was reported as missing in Greece for some reason or other, but when we were getting off the ship going down the gangway because it was high tide and it was very steep down the gangway, a fella said to me “Oh we’re being filmed.” and I looked up to see where the camera was and of course missed my footing and tumbled down and apparently this was a newsreel and my family found out that I was alright and wasn’t missing at all that I’d safely got back.”

Bill continued to fight in both the Syrian and Papuan campaigns. Eventually, he went home and spent six months in a hospital for all the ailments he had contracted over the years of harsh battlefield conditions. After being discharged, he got married and fathered three children. He found a job in the Department of Health and rose to become advisor to the Minister of Health.

Podcasts about Australians in the Mediterranean during WWII

Did my Relative Serve in these Battles?

Hundreds of thousands of Australians served in the Mediterranean during the Second World War. Some families know what their relative experienced during this often very important part of their life, but many do not. If you have a relative who served in the Australian armed forces during WWII and would like to know if they served in the Mediterranean please fill in the form below.

History Guild volunteers will research your relative’s service history and let you know what they find. As this is a free service provided by volunteers the timeframe may vary.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.