AUSTRALIA’S WAR WITH FRANCE

Reading time: 12 minutes

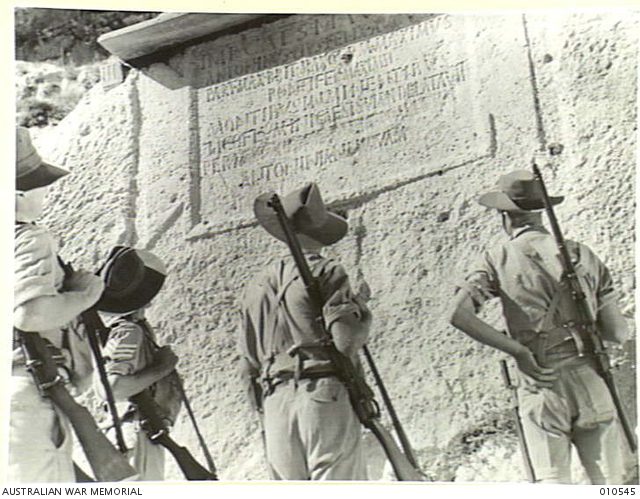

The Nahr al-Kalb, or ‘Dog River’, meets the Mediterranean Sea just north of Beirut, after meandering thirty kilometres downstream from its wellspring in the Lebanon range. A four-lane highway overpass runs along this stretch of coast, and tentacles of concrete obscure the river mouth. The strip of land to the north and south has been reclaimed from the sea. It’s a flat, featureless stretch of windblown sand and garbage. In ancient times, though, the view was very different. The steep riverbanks dropped straight into the ocean, and the Lycus, as the river was then known, was a significant obstacle to conquering armies. Ramases II carved a monument into the rock when he passed this way, as did Nebuchadnezzar, Marcus Aurelius, and various Assyrian kings. When Napoleon III sent an army to the Levant, his soldiers also carved an impressive memorial to their emperor—right over the top of Ramases’ inscription which, until then, had stood proudly for two-and-a-half millennia.

By Richard James, author of Australia’s War with France: The Campaign in Syria and Lebanon, 1941.

A modern-day tourist, after dodging traffic from an off-ramp and pulling away a few weeds, can still view these glorious engravings. The history they tell is of an ancient and war-scarred land. The British continued the tradition when General Edmund Allenby conquered Ottoman-ruled Syria and Lebanon during the Great War. That inscription pays homage to the Australian Light Horse, who routed the Turks at Beersheba and pushed on to capture Damascus and Aleppo, paving the way for the French mandate and ending Syria’s four centuries under the yoke of the Ottoman Empire. Those horsemen are now an Australian legend; and the mystique, if not the detail, of their exploits is part of our nation’s consciousness. But another nearby monument makes mention of a conflict that is not so well recalled:

JUNE–JULY 1941

FIRST AUSTRALIAN CORPS CAPTURED DAMOUR

WHILE BRITISH, INDIAN, AUSTRALIAN AND

FREE FRENCH TROOPS CAPTURED DAMASCUS

BRINGING FREEDOM

TO SYRIA AND LEBANON

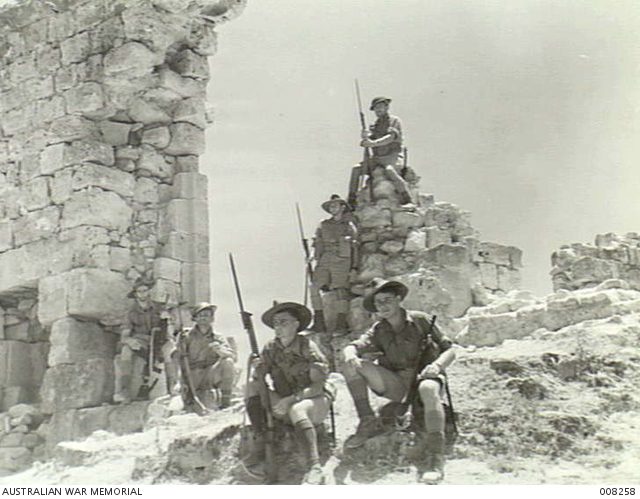

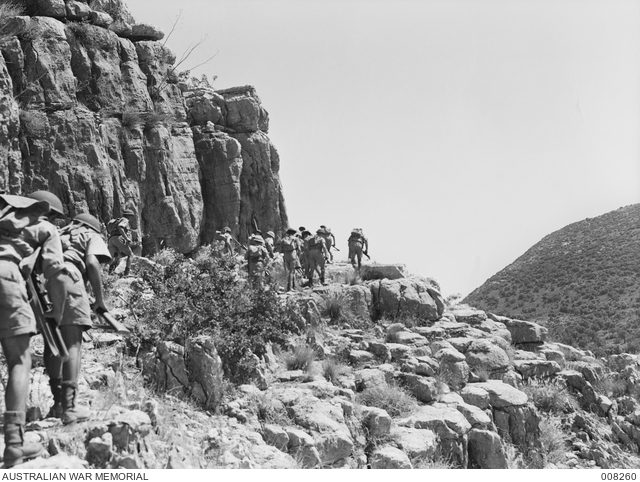

It has almost been forgotten that our soldiers were back here again a generation later, once again at the behest of the United Kingdom, fighting a strange war against confused Frenchmen who were not supposed to be our enemy. France had been defeated and subjugated by the Germans. The new French government, installed at Vichy, was answerable to the Führer. With France vanquished, the fate of the mandate in Syria and Lebanon became uncertain. The British—urged on by Charles de Gaulle, whose Free French movement had received British sponsorship—sent in the Australian 7th Division to seize it, not expecting that the French Army of the Levant, in defence of its military honour, would put up a fight.

In the popular consciousness, Australia and France are allies. Most of these Australian soldiers had fathers and uncles who had fought in the Great War. Many had lost their lives or limbs on the Western Front, fighting in the name of France, defending its territory against the Germans. These young Australian troops assembled in British Palestine, nervous and untested in warfare, about to fire their first ever shots in anger –against the French.

The Australians who invaded Syria and Lebanon had to make some kind of justification. The popular view was that the French soldiers in the Levant were an evil bunch who had decided to cooperate with Hitler and the Nazis. Roald Dahl, who participated in the campaign as an RAF pilot, summed them up as ‘disgusting pro-Nazi Frenchmen’ who were ‘fanatically anti-British and pro-German’. The Australians tended to agree with this simplistic interpretation.

But who exactly were these French soldiers? The Army of the Levant, as the French force in Syria and Lebanon was known, comprised colonial troops from North Africa, local Syrian and Lebanese levies and reservists from metropolitan France. There were also several battalions of that mysterious and romantic army, the French Foreign Legion. The commander-in-chief of the Army of the Levant was General Henri Dentz, who also served in a political capacity as French High Commissioner.

Dentz is portrayed as evil and duplicitous in Allied historical accounts, but he was a man in an impossible situation. His official mandate was to keep the Levant neutral, and he had some degree of independence from the Vichy government in mainland France. Far from being a closet Nazi, Dentz—along with most soldiers in the Army of the Levant—sympathised much more strongly with the British than the Germans. He was forced to allow Luftwaffe planes to land and refuel at Syrian airfields, and this almost led to a mutiny amongst his officers. One can almost feel the painful turnings of his conscience as events unfolded. All the decisions which led to war in Syria were forced upon Dentz by the Vichy administration, and he did not follow orders blindly. He questioned them from both practical and ethical points of view. In the end he had no choice but to obey, because duty to the fatherland was his overriding principle.

The situation in the Levant was complicated by the participation of Charles de Gaulle. At that stage, de Gaulle was far from the conquering hero who would go on to become President of France. In the early years of the war he was seen by most Frenchmen as a traitor and a British lackey. His tiny, ramshackle army was inconsequential. His invitation to participate in the Allied campaign was a favour from Churchill, in an effort to gain some political clout for his cause.

The politicians and generals in London and British Cairo did not expect that the Army of the Levant would resist. Churchill regarded the Syrian affair as ‘a political coup . . . rather than as a military operation’. General Wavell, commander-in-chief of British forces in the Middle East, assumed that the campaign would be won ‘by propaganda, leaflets and showing attitude of force’, rather than fighting. Gaullist liaison officers were attached to the head of each offensive column like ‘a piece of sugar’, in an attempt to win over the French defenders with ‘persuasion before fighting’.

British intelligence seriously misjudged the political attitude inside Syria and Lebanon. The Army of the Levant fought fiercely, and the result was a five-week-long campaign in which around 2000 men lost their lives. The Allies won the war, but no-one in the British hierarchy had expected such bloodshed. The soldiers of the Army of the Levant reserved a special antipathy for the traitorous Gaullists, and in some areas the fighting resembled a French civil war, with all the fanaticism and bitterness that such a conflict can provoke.

The Australians were caught in the middle of all this. They were ordered into battle wearing their slouch hats in the hope of playing on French sympathies for Australian sacrifices made in France during the previous war. The defenders were unmoved by this gesture. The Australian force came under a rain of fire within hours of crossing the border. Colin Kerr, an Australian soldier who participated in the campaign, described the reaction:

‘The words, “the bastards”, shaped themselves on people’s lips. Henceforth that’s what the enemy were to be, nothing more than that, whether they came from Paris or Provençe or African villages, whether they were hardened legionnaires or youngsters like the badly wounded kid who caught hold of my hand one day on the road to Beirut and wept out of sheer loneliness and bewilderment.’

The Australians emerged victorious in their first taste of battle, but at the price of more than 400 young men, sons of Anzacs who had fought to defend France in the trenches of the Western Front. The British were embarrassed, the campaign was forgotten, and the Australians who fought were dubbed the ‘silent men’. On 22 June, as the Australian force entered Damascus, Germany invaded the Soviet Union. This shifted the entire focus of the war away from the Middle East. Alan Moorehead, an Australian war correspondent who had been covering the operation in Syria, summed it up: ‘Compared to this news, my reportage of the fall of Damascus had no interest! I left immediately . . .’ The confused little war in the Levant was consigned to the dustbin of history.

There was no deliberate subterfuge or conspiracy by the Australian government or military to keep the story of the campaign silent. The Australian newspapers were reporting freely on the campaign. For the Australian public, the fact that the exploits of the men in Syria were overshadowed by other events, such as the exploits of the ‘Rats of Tobruk’, is probably a reflection of the fact that the actions of the latter, a small bunch of valiant Australians holding out against marauding German panzers, made for more exciting newspaper copy than the odd, confusing little campaign in the Levant.

Whist the Allies were keen to forget the whole affair, the Syrians and Lebanese viewed the conflict as a chance for liberation. The Gaullists clung to a stale notion of French colonial glory, but it was British guns that held the peace. The Second World War marked the end of direct French control in the Levant. Independence came to both Syria and Lebanon in 1943. By that time the Australians of the 7th Division had long since returned home and had fought a new war—on the Kokoda Track, against the Japanese—which sealed their own place in history. Even that recognition was late in coming, and the story of Australia’s involvement in the Levant in 1941 remains largely untold. Sir Basil Henry Liddell Hart’s History of the Second World War does not mention it. Antony Beevor’s The Second World War only devotes half a page to it. In Australia, a comprehensive account of the military campaign can be found in the battalion histories, but the geopolitical causes of the conflict, and the motivations of the enemy, are not well understood. To Australians, the ‘Vichy French’ who fought in the Levant were ‘not really French, but . . . a separate species, now extinct in the incomprehensible meanderings of time.’

General Dentz, who had commanded the Army of the Levant, was arrested by the Allies when Paris was liberated in September 1944. He was put on trial for treason and brought before the High Court of Justice in April 1944. He died in prison the following year. By then, the Vichy era was like a murky dream. De Gaulle was the saviour of France and Marshal Pétain—once venerated like the fatherland itself—had been forgotten.

Kenneth Slessor, the Australian poet who was in Syria as a war correspondent, described the atmosphere at the end of the campaign:

‘Today the crickets are singing in the trampled grass of the battlefield; corn is dancing on the skyline and farm boys are winnowing the crops. The earth has received the scattered bones of war and forgotten them. Syria, too, in a few weeks will forget, let us hope, the cloud which passed over its green fields.’

In the Levant today, the events of 1941 are like ancient history. They seem as far lost to the past as the antiquated inscriptions of exotic kings at the Dog River. Both Lebanon and Syria have since fought their own civil wars, and many millions have been killed. In the Near East it seems that conflict is the natural state of things. Amidst so much death and destruction, it is easy to overlook the 416 Australian graves, scattered in dilapidated war cemeteries in Beirut and Damascus. They are buried far from home, and have long been forgotten both in the land of their birth and the land of their death. To write them a meaningful epitaph is very difficult. They simply died in a war that should never have been fought.

History Guild has organised a discussion between Richard James, author of Australia’s War with France: The Campaign in Syria and Lebanon, 1941 and Angus Wallace, creator of the fantastic WW2 Podcast. Listen to this podcast below.

Richard James is a tour operator specialising in historical treks of the Kokoda Track in Papua New Guinea. He has personally led hundreds of Australians across the Kokoda Track and has met many war veterans from the 7th Division who fought in Syria before going on to fight on the Kokoda track the following year.

This Video provides a good overview of the campaign.

This project commemorating the service by Victorians in the Mediterranean theatre of WW2 was supported by the Victorian Government and the Victorian Veterans Council. Sign up to the newsletter at the bottom of the page to be notified when the next article in this project is released.

Other Articles you may like

Australia’s war with France: The Campaign in Syria and Lebanon, 1941 – Podcast

AUSTRALIA’S WAR WITH FRANCE: THE CAMPAIGN IN SYRIA AND LEBANON, 1941 – PODCAST Operation Exporter was a little known, but very important campaign for the Australian military. It involved Australian’s fighting a strange war against confused Frenchmen who were not supposed to be our enemy. France had been defeated and subjugated by the Germans. The […]

The Benghazi Handicap and the Siege of Tobruk

The Benghazi handicap is the name Australian soldiers gave to their race to stay ahead of the German Afrika Korps in Libya, 1941. They won the race, but the reward was just to be besieged in the city of Tobruk for 241 days, the longest siege in British military history. In this article, we use the words of veterans themselves to describe these events, and how the Rats of Tobruk experienced the siege.

The Battle of Cape Spada: The Australian Navy Proves Its Mettle

Reading time: 9 minutes

The Battle of Cape Spada was a short, violent encounter on the 19th of July, 1940 where the cruiser HMAS Sydney of the Royal Australian Navy sank one Italian cruiser and severely damaged another off the coast of Crete. In this article, we go over the events of that day, as well as what life was like for the crew of the ship.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.