Reading time: 5 minutes

Last year, chair of the Australian War Memorial Kim Beazley called for First Nations “guerilla campaigns” of the Frontier Wars to be included in the Australian War Memorial. His bid was criticised by the RSL Australia’s president Major General Greg Melick.

By Ray Kerkhove (University of Southern Queensland) and Boe Skuthorpe-Spearim

Melick argued Indigenous casualties of the Frontier Wars could not be honoured at the War Memorial because they did not fight “in uniform”. But the Australian War Memorial already honours “ununiformed” First Nations soldiers – namely Dayak people who assisted in Borneo during World War 2.

Major General Melick’s criticism highlighted a misconception that First Nations’ warriors are not comparable to ANZAC soldiers. Many Australians do not believe First Nations people had military-style practices. Rather, they are regarded as victims of genocide.

Co-author Ray Kerkhove’s book How They Fought places First Nations’ practices within the framework of military history. This debunks the idea First Nations people lacked the structures and disciplines necessary to organise meaningful responses to the invasion.

Why recognition of First Nations’ fighting strategies matters

Australia is increasingly aware of the genocidal nature of its Frontier Wars. But as Historian Grace Karskens notes, this is often perceived as “no battles, no resistance and no survivors”.

Acknowledging massacres helps emphasise the inequalities in these conflicts. But categorising all skirmishes this way without acknowledging how First Nations people fought back, or were sometimes victorious, can indirectly imply First Nations peoples were always passive victims.

The broader implications of this narrative have impacted public education. Historians Matthew Bailey and Sean Brawley found both teachers and the wider community had difficulty accepting Australia’s frontier conflicts as “war”, because they had been presented to them as one-sided slaughter.

Thankfully, Arrernte and Kalkadoon director Rachel Perkins’ documentary series recently reinstated Aboriginal peoples’ resistance as historical reality. Even so, Australia’s collective understanding of how Aboriginal peoples fought back remains limited.

We still know quite little of the “guerrilla campaigns” Kim Beazley wants to honour. For instance, the complex inter-group negotiations across mobs.

Many other questions remain unanswered: how were warriors organised for attacks? How effective were their actions? What strategies were employed?

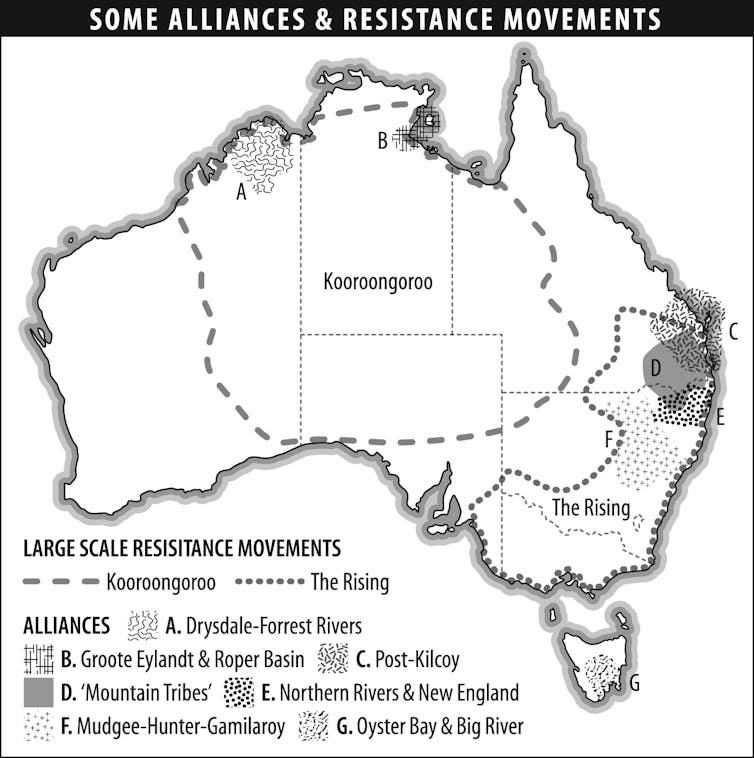

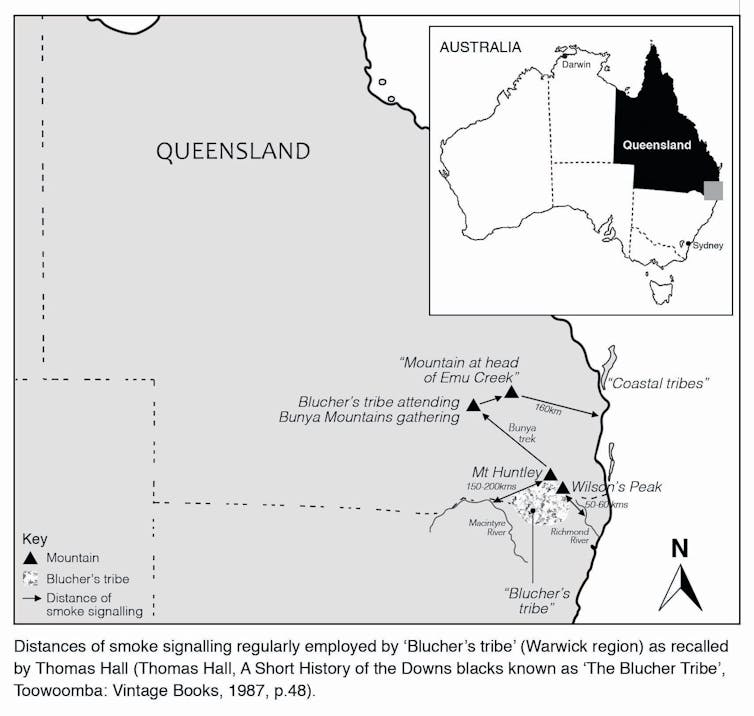

A small start was made in 2017 through a visiting fellowship with the Harry Gentle Resource Centre (Griffith University). This project mapped the role of Birn, Bugurnuba and other inter-tribal alliances in pushing back against the invasion of south-east Queensland.

First Nations’ perspectives of frontier wars

Another breakthrough came through reconstructing First Nations’ historical perspectives of these wars. Two examples are Ambēyaŋ historian Callum Clayton-Dixon’s work in 2019: Surviving New England and (the same year) co-author Ray Kerkhove and historian Frank Uhr’s The Battle of One Tree Hill.

To amplify the work of his colleague Clayton-Dixon, Gamilaraay/ Kooma co-author Boe Skuthorpe-Spearim began presenting his own research on this topic in a podcast series called Frontier Wars. Boe’s research methods included yarns with Elders and historians.

As a Knowledge sharer, Boe’s podcasts affirmed growing evidence the Frontier Wars were more than massacres. This was a truth historians Nicholas Clements and Henry Reynolds were also unveiling in Tasmania, as was historian Stephen Gapps in collaboration with Wiradyuri people in central NSW.

It’s becoming more and more apparent that First Nations resistance was organised and efficient. Co-author Ray Kerkhove’s How They Fought identified specific structures and tactics First Nations peoples’ employed during the Frontier Wars. Kerkhove analysed over 200 written reminiscences and hundreds of settler and First Nations accounts of skirmishes across Australia.

Kerkhove’s How They Fought suggests resistance was mostly a “slow drip” of constant harassment against the colonisers – but effective in halting settlement for many years in some regions. It identifies the complex tactics First Nations groups developed for raids, sieges, pitched battles and even their attempts to take over the pastoral industry of particular regions within the Northern Territory and South Australia.

Kerkhove’s research proposes First Nations’ forces had military-style training, ranking, “policing” patrols, defensive ‘bastions’, and intelligence networks. The research highlights the frequency and scale of inter-tribal meetings and partnerships during the Frontier Wars – for instance, in Tasmania, southern Queensland and western NSW. It finds traditional weapons were effective in causing many settler fatalities. The research also finds many new weapons, fire, steel, glass, guns and horses were adopted to halt the tide of settlement.

The sophistication of First Nations warfare needs to be acknowledged

Australia needs to understand the Frontier Wars were more than a sequence of massacres. Mob fought back. They had victories. First Nations peoples quickly recognised they were dealing with an existential threat, and created widespread resistance. This history is finally being written.

Many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples emphasise the deep pain they feel when ANZAC rolls around each year, knowing Australia still does not formally recognise or acknowledge the blood, battles, lives and land that were lost.

Often this lack of recognition stems from limited knowledge of the sophistication of First Nations’ resistance. These “ununiformed” warriors had their own insignia and protocols. They acted with great valour and genius, against incredible odds. First Nations warriors should receive the same dignity we accord our ANZAC fallen.

This article was originally published by The Conversation.

Podcasts about Aboriginal Resistance

Articles you may also like

Weekly History Quiz No.268

1. Where did Joanna Plantagenet, sister of Richard I Lionheart, become Queen?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

The USAAF 49th Fighter Group over Darwin: a forgotten campaign – Video

The prelude to the campaign of the 49th Fighter Group covers some of the darkest days of the Pacific War: the fall of Singapore on 15 February; the bombing of Darwin on 19 February during which the Japanese shot down nine of the ten P-40s of Major Floyd Pell’s 33rd Pursuit Squadron; and the sinking […]

General History Quiz 151

1. Which was the first country to be ruled by a Fascist government?

Try the full 10 question quiz.

The text of this article is republished from The Conversation in accordance with their republishing policy and is licenced under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license.