Reading time: 3 minutes

The working day as we now know it was the result of international, cross-industry labour efforts from workers, unions and activists, spanning well over a century of campaign, unrest and even death. The Industrial Revolution, with the spread of electrical lighting and extremely low hourly wages, had ended the traditional, rural working patterns of sun up to sun down, and meant that in some industries workers were forced to endure up to 18-hour shifts.

By Anna McEvinney

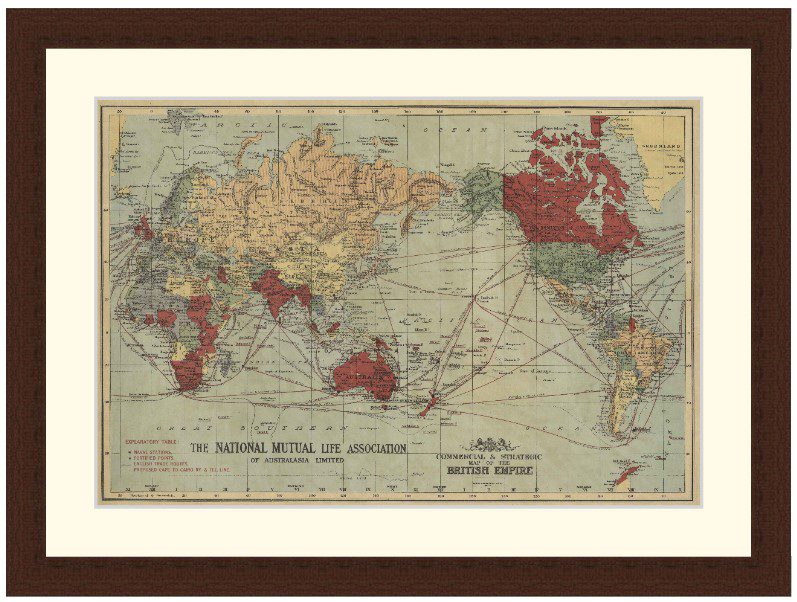

The cause was spearheaded primarily by workers in Australia, Britain and the USA. Each nation had its own nuanced conditions and reasoning for campaign: In Australia, for example, the end of transportation in the 1840s and the movement of many labourers to the goldfields led to a shortage of workers and thus increased bargaining power. Moreover, the Melbourne Stonemason’s Union cited the unbearably hot summer weather as a basis for reducing the working day from ten hours. In 1856, led by the union, workers downed tools and over several months negotiated for themselves an eight-hour day, maintaining their ten-hour wages. This was the cornerstone on which the fight for a universal eight-hour day was built.

In the US, campaigning for an eight-hour day had tentatively begun in 1791, when Philadelphia workers had organised to campaign for a ten-hour day, including two hours for meals. Over decades, intermittent strikes and protests continued along with the formation of several ‘Eight Hour Leagues’, until things came to a head at the inaugural May Day Parade of 1886. 350,000 workers walked out of their positions to protest for shorter working hours, and over the next few days matters became heated. Things came to a head when police opened fire on a protesting crowd, killing four.

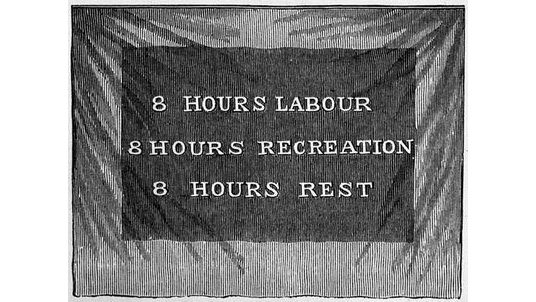

In 1817, the British proto-socialist Robert Owen, of New Lanark, coined his slogan: ‘Eight Hours’ Work, Eight Hours’ Rest, Eight Hours’ Recreation’. Unpopular amongst business owners, the campaign did not gain widespread traction until in 1884 Robert Mann founded the Eight Hour League, which convinced the Trades Union Congress to establish the eight-hour day as one of their foremost goals — a crucial step.

Decades of activism were the primary driving force for the eight-hour day, but there were other factors in play. Henry Ford, the famous motoring manufacturer, is often considered one of the catalysts behind the decrease in working hours. In 1914, he doubled employee wages and cut their hours from 48 to 40 per week. Ford realised that he could make more money, and retain greater employee loyalty, by reducing working hours. In 1926, he argued: ‘It is high time to rid ourselves of the notion that leisure for workmen is either “lost time” or a class privilege’. Seeing the success of his venture, some other employers tentatively followed, and the forty-hour working week gradually became more widespread, until finally the Fair Labour Standards Act was introduced in 1938, assuring a forty-hour working week for all.

There was even more nuance to the decrease in working hours: the foundations of the eight-hour working day were laid during the Victorian period, famous for its preoccupation with virtue. There was general concern about the moral lives and education of workers, and it was argued that an eight-hour day would allow ample leisure time for employees to morally educate themselves, and to act in their free time as upstanding citizens and attentive fathers and husbands.

The video below describes how this came about.

Podcast Episodes about the 8 Hour Working Day

Articles you may also like

The Thucydides Trap: Vital lessons from ancient Greece for China and the US … or a load of old claptrap?

Reading time: 5 minutes

The so-called Thucydides Trap has become a staple of foreign policy commentary over the past decade or so, regularly invoked to frame the escalating rivalry between the United States and China.

Coined by political scientist Graham Allison — first in a 2012 Financial Times article and later developed in his 2017 book “Destined for War” — the phrase refers to a line from the ancient Greek historian Thucydides, who wrote in his “History of the Peloponnesian War,” “It was the rise of Athens and the fear that this instilled in Sparta that made war inevitable.”

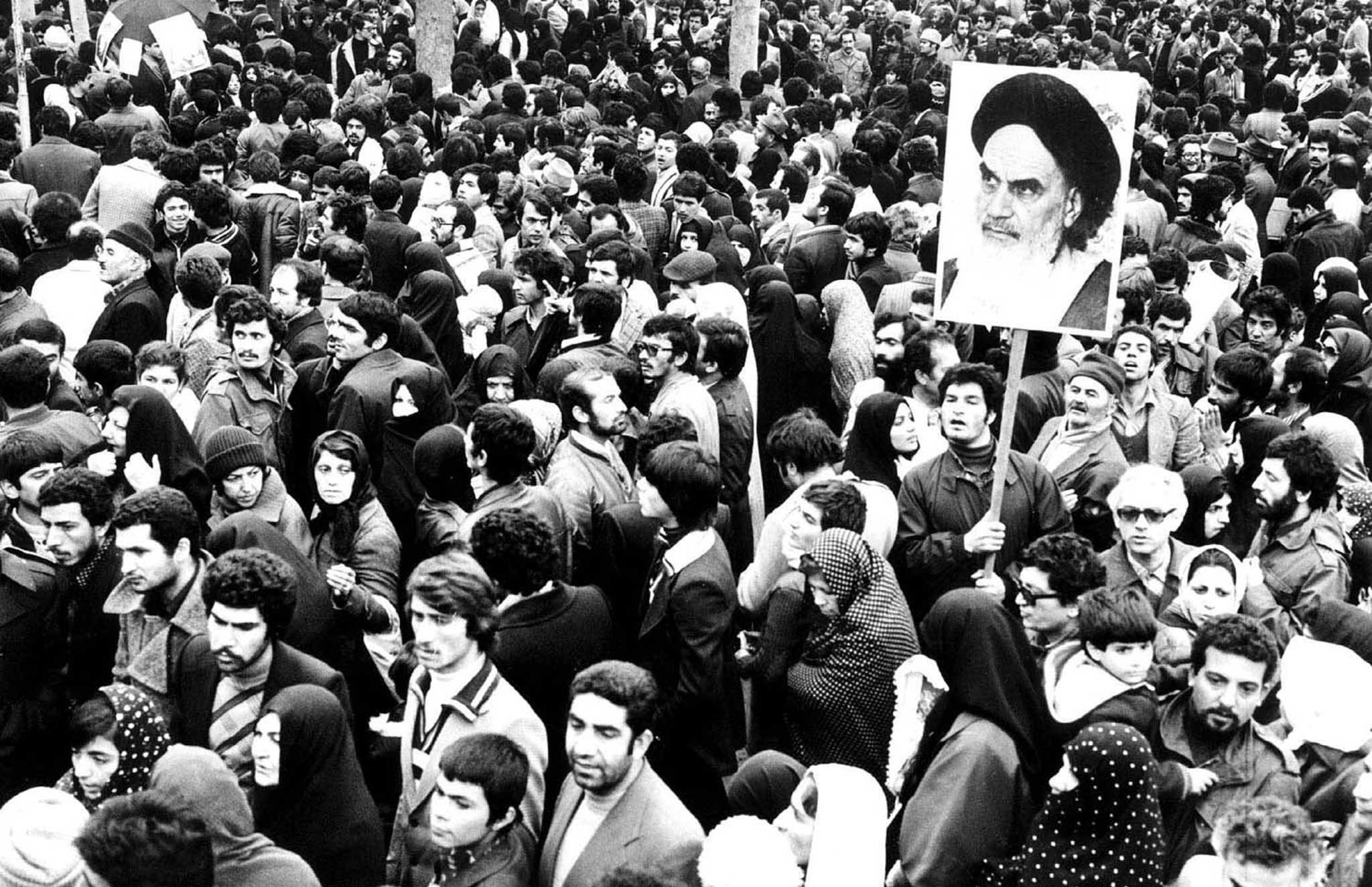

The Iranian Revolution

To understand what caused the Iranian Revolution, we must first consider the ongoing conflict between proponents of secular versus Islamic models of governance in Muslim societies. It all began with the British colonisation of India in 1858, which precipitated the collapse of classic Islamic civilisation. By early 20th century, almost the entire Muslim world was colonised […]

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks