In May of 1941, as the German invasion of Crete threatened to swamp the island, a single Australian Army Brigade would find itself fighting for its life around Rethimno and its landing strip. Approaching Rethimno was the best of the best of the German army: 1,700 paratroopers of the I and III Battalions, 2nd Parachute Regiment, 7th Air Division, XI Air Corps.

Australian Army Corporal John Robinson found himself in the thick of battle on the slopes of one of the surrounding hills.

I was hit in the head, the bullet entering my steel helmet where the fastening bolt holds the head lining to the helmet. My scalp was cut and bled quite badly. The bullet lodged in the lining where I found it the next day. From every side, I am now hearing the banging of rifles and light machine guns, and in the air the explosions of anti-aircraft shells. Also, the screams of those wounded in the air. There is one man in the air who is bursting almost to pieces.

Corporal John Robinson, 2/1st Battalion

The German paratroopers were slaughtered wholesale by the Australians as they dangled helplessly from their parachutes. A German corporal who survived the air assault remembers the bodies of his comrades all around him.

The intense battle that enveloped the hills and vineyards of Rethimno would only grow more ferocious in the next days and would lead to the death and capture of nearly a thousand Australian soldiers. The Australian public did not fully understand the true extent of the battle until long after the war. This is their story.

By Nathan Drescher.

At the end of the long fighting withdrawal that was the Australian experience of the Battle of Greece, the Australians found themselves fighting a sharp rearguard action at Porto Rafti. They held off the Germans as the expeditionary force was evacuated in a ‘mini Dunkirk’. The brigades of the Australian 6th Division got all mixed up when it was finally their turn to embark, and they were some of the last men to leave Greece as the German panzers closed in on them.

The 16th and 17th Brigades were sent to Alexandria, in Egypt, but several of their battalions were landed in Crete. The entire 19th Brigade was also landed in Crete. Two field regiments of Divisional artillery were also landed in Crete.

All these disparate battalions were cobbled together to form a temporary composite brigade, the 14th. These two Australian brigades were given a new task: defend the region of Rethimno on the north coast of central Crete.

The Crete Garrison

Brigade Major Ian Ross Campbell had been leading the 16th Brigade in Greece, but most of his command had ended up in Alexandria while he had landed in Crete. He was promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel and given command of the entire Rethimno defense. He had 1,270 Australian men under his command and eight field guns, including four captured Italian 100 mm heavy guns. There were other units of the 6th scattered across the island, but they were serving under different commands. The overall defense of Crete was entrusted to the New Zealander, General Bernard Freyberg.

Several units of Greek soldiers were added to Campbell’s command, along with some local policemen from the town. These forces were in a sad state. Many of the Greeks didn’t have weapons. Some had no boots. Campbell sent several of them home, but he did find the local police were serious and had pistols and a few rifles. Ammunition was a bigger problem, with most of the Greeks in possession of only three rounds a piece.

The situation got worse when the RAF squadrons of Hurricanes and Blenheims were evacuated from the island shortly after the survivors of Greece arrived. There would be no air cover for the defenders. General Freyberg protested but to little avail. The Empire simply didn’t have enough aircraft to cover all of its fronts, and Crete was considered a lower priority.

Freyberg chose to focus the island defenses on repulsing a seaborne invasion. He was a veteran of Gallipoli and the Somme and had even won a Victoria Cross in the Great War, and he may have had a difficult time comprehending the threat of an airborne invasion. But General Freyberg had Ultra intercepts from the successful British efforts to break the German Enigma code, which indicated the Germans were planning an airborne operation.

“It is learned that to enable GAF (German Air Force) to carry out operations planned for the coming weeks COMMA enemy will not mine Suda Bay nor destroy aerodromes on Crete,” read one Ultra dispatch, dated May 1st 1941.

“Grand parade German army air units begins May third,” read another. “Italians also represented.”

“Preparations for operations against Crete probably complete on one seven REPEAT one seven May STOP sequence of landing from zero day onward will be parachute landing of seven fliegerdivision plus corps troops to seize Maleme Candia and Retimo,” was another of the Ultra decrypts in Freyberg’s hands.

He also received intelligence about German Luftwaffe staff officers meeting in Athens, as well as details of individual German parachute units assembling and their preparations at airfields throughout southern Greece. Nevertheless, Freyberg continued to ignore the reports and focused most of his defenses along the coast, where he expected a seaborne landing.

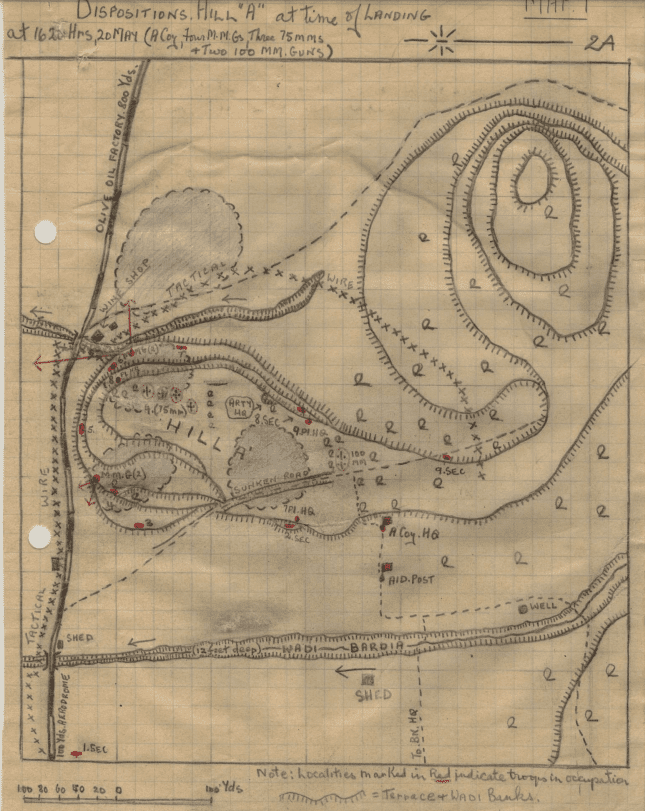

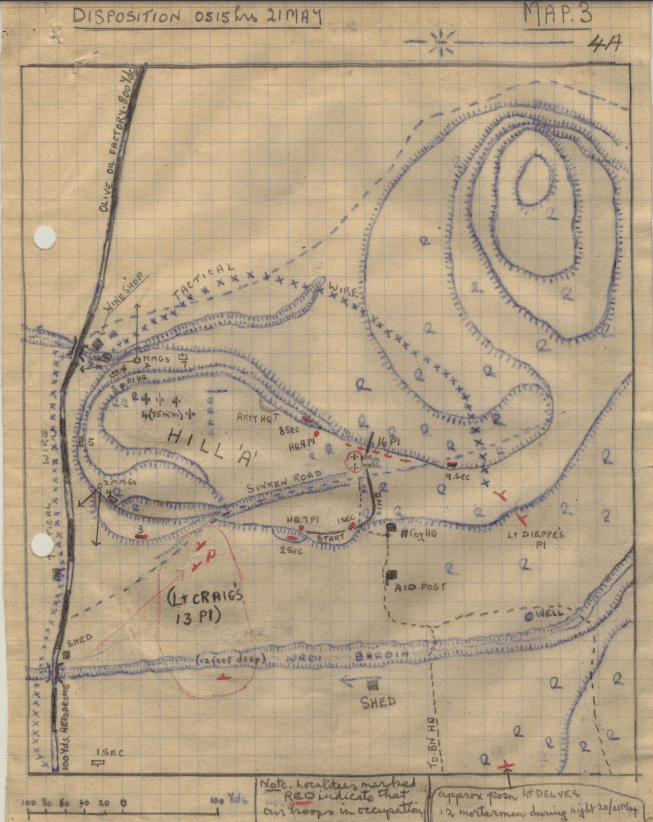

That’s not to say no preparations were made against airborne landings. Barrels filled with sand were lined up along the runway at Rethimno to prevent German planes from landing. There were two hills connected by a ridge overlooking the airfield, Hill A and Hill B. Col. Campbell dug two battalions in on these hills: 2/1st Battalion on Hill A with six guns and 2/11th Battalion on Hill B with the remaining two guns. He placed his HQ and the 4th Greek Battalion on the ridge between them, with the 5th Greek Battalion to the rear. He also had two British Matilda tanks at his disposal, which he placed in a gully near the landing strip. Campbell and his mixed-up brigade didn’t have long to wait.

There was little or no leisure during the ensuing few days which were occupied in digging our two guns into pits, camouflaging them and preparing our defences for the assault that was expected at any hour. The guns were in the corners of a wheat field on the side of a hill (Hill A) overlooking the aerodrome. At thirty yards distance they were invisible, a feat of camouflage of which were were very proud. Lacking camouflage nets we had requisitioned fishing nets in the town and woven them with wheat stalks.

Lew Lind, 2/3rd Field Regiment

The Germans are coming

Preparing to drop onto the heads of the defenders on Crete were the 22,000 soldiers of the German XI Air Corps (Fliegerkorps XI). These men were highly trained and battle-hardened. They were veterans of campaigns in Norway, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Yugoslavia.

Only volunteers were accepted in the fallschirmjaeger and they had to pass grueling testing and training regimes to earn their right to join the division. Training consisted of intense live-fire infantry and anti-tank tactics, parachuting, field medicine, camouflage, and terrain navigation. It lasted three months and only the most determined and fittest managed to pass. The average age of a German paratrooper was under 20.

Their leader was Lieutenant-General Kurt Student. He’d been a fighter pilot in the Great War and had been one of the architects of the secretly rebuilt Nazi air force in the 1930s. The paratroopers were his idea. He envisioned an airborne force dropping suddenly behind enemy lines and seizing important bridges and airfields, sowing chaos and confusion in the rear. Hitler and Goering loved his ideas and he was given the go-ahead to build an airborne division in 1938.

Student was a devout Nazi and admirer of Adolf Hitler. He was captured in 1945 and put on trial for war crimes in 1947 for the murder of Prisoners of War in Norway and Crete. He only served one year behind bars, despite being found guilty.

Fallschirmjaeger exclusively used the Ju-52 three-engine troop transport and leapt out of a door in the rear of the fuselage. The plane could carry 18 men but only 12 for airborne assaults with the additional equipment and weapons. Each man wore an RZ16 parachute attached by a static line to the aircraft, which yanked the parachute out of the pack as he dropped. He carried several grenades, a pistol, a field first aid kit, and a water canteen. His primary weapons and ammunition were dropped separately through chutes in the sides of the Ju-52. This meant German paratroopers were very lightly armed until they were able to retrieve their weapons bundles.

They had learned early on to jump from low altitude to lessen the spread of the troopers, ensuring they landed close to their weapons and each other. This put the slow-moving and unarmed transports at risk from anti-aircraft fire. However, the Luftwaffe had assured General Student that they would have complete air dominance over Crete and would neutralise anti-air defenses.

Operation Mercury

The airborne invasion of Crete was codenamed Operation Mercury by Student and his planning staff. They were excited to attempt an invasion by air alone, something that had never been done before. The rest of the German general staff was not so enthused.

OKH (Oberkommando der Heer), the supreme command of the German armed forces, was busy preparing for the invasion of the Soviet Union and considered the Crete adventure an unwelcome sideshow. However, Hitler was concerned that the island could be used for bombing raids on the vital Ploesti oil fields, which supplied the bulk of the German army. The Abwher, the German intelligence service, estimated there were more than 5,000 British troops on Crete and warned against an unsupported airborne landing.

Hitler persisted and Student was given the go-ahead to invade Crete by air. The Italian navy would give what support it could, but the bulk of the German panzer divisions would not be available.

The plans were for several waves of paratroopers to seize three key airfields on the island. More troops and heavier weapons could then be brought in by plane to push the invasion down the middle of the island. Fliegerkorps XI of the Luftwaffe would have overall command of the operation. They had 330 bombers, 180 fighters, and 500 Ju-52 transports for the operation.

10,000 paratroopers would capture the airfields of Maleme, Heraklion, and Rethimno in a mass daylight airdrop. Once the fields were in German hands and any supporting AA guns were destroyed, 5,000 mountain troops of the 5th Mountain Division and their light panzers would be airlifted in and would push south, splitting the Commonwealth forces in half. The entire invasion would be preceded by a raid on several bridges by 750 elite glider troops.

Death and Chaos in the Skies Over Crete

The operation got off to a bad start. The Greek airfields from which Fliegerkorps XI was meant to operate had been hastily built and were in a state of disarray. Hundreds of Ju-52s had been landing in the weeks leading up to the operation and there was no room for them. Some planes were parked on the roads of local towns and in farm fields.

It took two hours on the morning of 20th May 1941 for the first two dozen planes to get airborne and head toward Crete. They had no fighter escort. There were no bombers or Bf-110s with them. The paratroopers would be landing in several disparate waves, rather than all together as originally planned.

These were the men of the 1st Assault Regiment and they began jumping out of their planes over Maleme airfield at 0800. They found themselves engulfed in fire from the ground. The defenders were New Zealanders and they shot the German paratroopers as they dangled helplessly from their parachutes, unable to fire back.

The 1st Regiment suffered nearly 800 of their 1,000 men killed in the initial assault, and the survivors were pinned down and many were wounded. Several hundred paratroopers missed their drop zones and dug in on the hills around the airfield. Although they failed to capture the airfield, they did force the New Zealanders to mount several assaults to push them off the hills.

Several of the Ju-52s were damaged from this wave and they crash-landed back in Greece, clogging up the airfields and further delaying the operation. The planned assault on Rethimno was to include a pre-invasion strike by aircraft to soften up the defenses, but fewer than 20 Bf-110s and a couple of Ju-88s were able to get airborne. They screamed out of the sky and caused a ruckus with their bombs and cannon fire, but they hit little of value. The paratroopers who were supposed to be right behind them hadn’t even left the ground yet.

It wasn’t until 16:15 that the first 24 Ju-52s appeared at Rethimno, flying parallel to the coast. They were low and slow and did not take any evasive maneuvers. Australian ack-ack opened up and several of the troop-laden transports were blown out of the sky. Nine transports crash-landed near Hill B. At least two were seen flying back over the horizon with long plumes of black smoke trailing out behind them.

The remaining turned inland over the airfield and began disgorging their paratroopers. There seemed to be no order. The planes, bracketed by heavy ground fire, lost organization and the men on board began jumping as soon as they could. Several landed in the sea and drowned. A dozen men were impaled when they came down in a cane break filled with bamboo.

136 more transports were coming in directly behind this first group and they met the same intense AA fire. This was the main assault on the island and the pilots were following the coast road, which led right through Rethimno and the guns of the Australians dug in there. Seven were shot down, crashing along the beach or exploding in the air in a fireball. Many more were damaged.

The men on board began jumping. One platoon sergeant was killed by AA fire as he stood in the doorway of his Junkers, preparing to jump. The plane was hit and crashed into the ocean. The survivors managed to get into a dinghy but many were cut down by machine gun fire from the Australians on the hills. Only two survived.

The leading planes of the armada had passed overhead,” recalled one British officer. “When the hatches opened small black objects came tumbling out, and, in the space of a few seconds, the air above and over the valley beyond was filled with hundreds of men dangling on their parachutes, swaying this way and that…Every soldier selected a swaying figure, sight on target, drop a yard for ‘aim-off’, then swiftly fingers squeezed triggers with ‘a mad excitement’

Lieutenant Colonel Gerald Barry, BLack Watch

One Australian private dug in on Hill A recalled the carnage his Bren gun crew caused among the paratroopers dangling helplessly in their parachutes.

I turned the Bren on the men coming down. They landed all around our position, right on top of us. In fact, some dropped into alternative positions we had dug, and they used them. I got many in the first wave. They were so close, you couldn’t miss. As they got down, the crossfire started. It was like Empire Day, with everyone firing!

Pte James “Lofty” McKie, 9 Platoon, A Company, 2/1st Battalion

Lieutenant Noel Craig, in command of 13 platoon, C Company, 2/1st Battalion, was shaken up by the scene.

They came in from the sea, turned west, and as Ian Campbell had instructed us, we hit them in the planes, in the air, and if they reached the ground alive, we kicked them in the ass,” he said. “I’ll never go duck hunting again.

Lieutenant Noel Craig, 13 Platoon, C Company, 2/1st Battalion

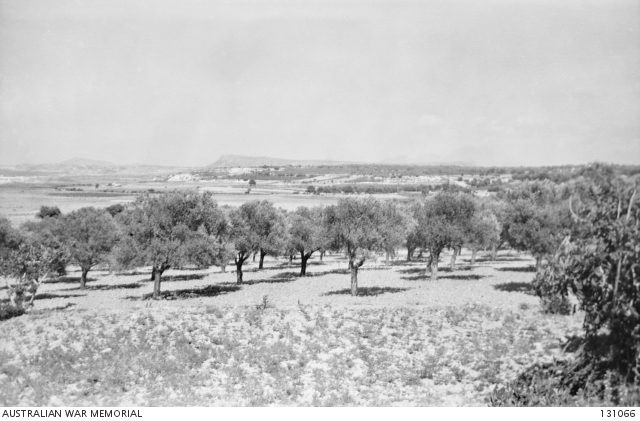

Two companies of Germans landed near Campbell’s HQ and were pinned by the incessant fire. The regimental headquarters, including commander Colonel Sturm, landed in the middle of Campbell’s HQ and they were all killed or captured within minutes. The rest of the men escaped by sneaking through the rocky brush to link up with another group who had landed close to an olive oil factory east of the airfield, directly in front of the men of 2/1st Battalion dug in on Hill A.

There were enough men to make up a small battalion and they were led by a veteran commander named Major Kroh. He organized his men and led a determined assault on Hill A. The weakened A Company 2/1st Battalion was overrun – many of the 2/1st Machine Gun Battalion manning the Vickers machine guns was killed as the paratroopers stormed up the slopes. They overran the 2/3rd Field Regiment with two 75 mm guns, who withdrew, taking the breech blocks of the artillery with them. The survivors of A Company, 2/1th Infantry Battalion, retreated down the south-west slopes of the hill.

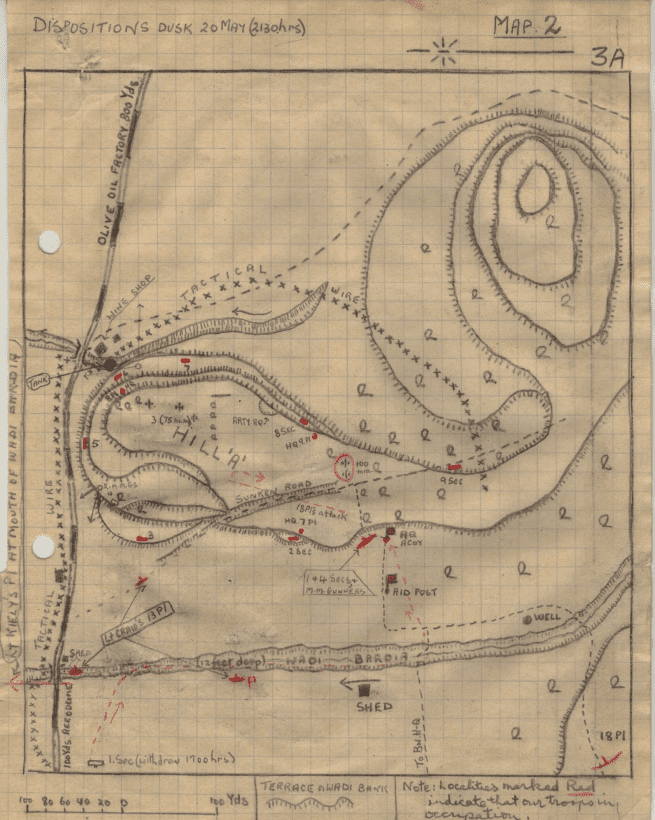

Colonel Campbell followed the events closely and quickly organised a counter-attack using the two Matilda tanks he had kept for just such an emergency. But the tanks both got stuck in the rocky terrain and could not advance. With no armored support and 400 Germans dug in on the vital hill, Campbell was forced to call off the attack. He dug several companies of troops in along the ridge between the hills instead. The artillerymen were forced to act as poorly equipped infantry throughout the night.

We were ordered to form a circle around the guns throughout the night to frustrate any enemy attempt to rush them. Straws were drawn to select the man who would have the rifle. The rest of us armed ourselves with shovels and pick-handles!

Lew Lind, 2/3rd Field Regiment

The Hills

The German III Parachute Battalion had landed at the base of Hill B and quickly captured the village of Perivolia, chasing away a surprised group of Greek troops in the process. The battalion next marched on the town of Rethimno around dusk, but they encountered fierce resistance from the Greek police, who were firing from windows and rooftops with pistols, shotguns, and rifles. Many civilians joined the local police, including two Orthodox priests. The firefight lasted over an hour. There was little cover for the Germans, with brushes and small rocks the only protection from the storm of fire blazing from the windows and rooftops of the village. The Germans were forced to retreat.

2/11th Battalion of the 19th Brigade were tasked with combing through the area to round up any Germans who might be hiding. They spent the night doing sweeps across the ridge and the Brigade HQ area and managed to round up 88 German prisoners.

The German force was split into two groups after that harrowing day. There was one group dug in on Hill A and another dug in between Hill B and Rethimno, where they had been repulsed by civilians earlier in the evening. Their command was scattered and none of their radio equipment had survived the initial assault, so they could not communicate with General Student or the rest of the landing force further west, who were battling the British and New Zealanders around Maleme.

The Germans weren’t the only ones with little information of the battle. Lt-Colonel Campbell had no contact with Freyberg’s headquarters, near Maleme, where a desperate battle for the airfield had been going on since early in the morning. He was not sure if there were more Germans on the way, or if he could expect any reinforcements. He did not know about the landings further east, at Heraklion. He decided the best course of action was to retake Hill A so he would at least have a better defensive position if more Germans showed up.

The 2/11th Battalion and several companies of Greek troops from the 5th Battalion attempted an attack on Hill A just before the sun came up on May 21st. The Germans were prepared and pinned the Australians and Greeks down with withering machine gun and rifle fire.

At 0525 sharp we moved out in one straight line, at walking pace, towards the enemy positions. After an advance of approximately 90 metres, the darkness was broken by heavy enemy machine gun fire which included a lot of red tracer. As we moved on under this fire for a short distance, the line on my left was seen to go to ground. We too were pinned down. After being pinned for some fifteen minutes, with the tracer just over our heads, the enemy started using their mortars. With the light of dawn appearing, under this heavy fire, the entire attacking force melted away.

Lieutenant Dieppe, 12 Platoon, B Company, 2/1st Battalion

Pte “Lofty” McKie, who had described the initial German assault, was also in this action. He wrote about it.

As I was snaking the through the vineyard, I turned to see who was snaking along behind me. It was a Jerry! They must have been trying to reinforce along the same route we were attacking on. The Jerry had a Tommy gun but he didn’t seem to be able to pull the trigger. I was!

Pte James “Lofty” McKie, 9 Platoon, A Company, 2/1st Battalion

They retreated just before sunrise with a dozen casualties.

As dawn broke, the 400 Germans of I Parachute Battalion on Hill A mounted a fierce assault on the airfield at the base of the hill. They opened with a brief mortar barrage and moved quickly in several assault groups while MG-34s provided cover fire. They captured the two Matilda tanks that had bogged down the day before and overran an Australian platoon that had become isolated from the rest of its company. Only intense mortar fire raining down from Hill B broke up the assault.

Mortars were a particularly deadly weapon on both sides of the battle. Mortars caused more than half of the casualties at Rethimno. There was little cover in the rocky terrain of Crete and shrapnel easily found victims. German paratroopers used a modified 81 mm mortar, called the “Kurz.” It had a range of up to 4 km and fired a light anti-personnel shell. The Australians were equipped with more than 20 three-inch Stokes mortars and three 4.2-inch heavy mortars.

A German Ju-88 bomber appeared out of nowhere and raced across the airfield, unloading a string of bombs directly onto the German positions. The Australians cheered. 16 Germans were killed in this friendly fire incident. The surviving fallschirmjaeger retreated back up the hill.

German mortars firing from Hill A had been falling on Lt-Col Campbell’s HQ area all night and had caused several casualties. He was determined to push them off the hill.

Campbell threw everything he had left from the 2/1st Battalion at the hill. The telephone lines had been broken so Campbell sent runners to assemble his last reserves in a ravine to the north of Hill, called Wadi Bardia. He then made his way alone to the wadi, dodging from cover to cover and avoiding occasional bursts of machine gun fire and sniper shots from the top of the hill.

He arrived at the wadi and found several survivors of the German attack on the airfield hunkered down, all of them wounded. None of his reserves he had called for had arrived, so he hung around for an anxious half hour until the men began to filter in. To the west of the wadi were the men of C Company, on a small ridge covered in trees. They were taking the brunt of the German fire from Hill A, but were returning a steady storm of fire themselves. This seemed to have kept the Germans distracted.

Campbell decided to launch an attack on the hill from both the east and west. He sent Captain Moriarty and C Company around to the east, and they launched an immediate attack. Two of his company’s platoons managed to gain the crest of the hill, where there was intense hand-to-hand fighting.

Campbell personally led his mixed force of reserves in an attack up the north-west slopes of the hill. It was a determined attack, with MG-34 rounds zipping through the air all around them. The long Australian “Gallipoli” bayonet caused many casualties among the German defenders, who retreated in a panic as the tall and ferocious men from New South Wales and Victoria swarmed up the hill.

“The Germans will still advance steadily against small arms fire,” Captain Coombs of “B” Company, 2/8th Battalion wrote “But at the first sight of the bayonet he will withdraw and if it is possible to exploit this trait of the German character by a strong and immediate counter-attack…I am of the opinion that success will always be achieved.”

Pte “Lofty” McKie was wounded in this attack.

I was with Lte Whittle and Pte Chinnery when a mortar shell dropped beside us. We were only 45 metres from the Germans then. Fragments caught me on both legs, but not seriously. Chinnery’s shoulder and neck were torn open, and he was in a bad way. I dropped back to get a stretcher party…when I got a burst in the back from a machine gun.

Pte James “Lofty” McKie, 9 Platoon, A Company, 2/1st Battalion

McKie spent the rest of the morning laying where he had fallen near a small olive grove. He was eventually found and taken to an aid station.

Campbell’s attack took the hill and captured 69 German prisoners. The battalion also recovered the two Matilda tanks and pushed the stricken Germans off the airfield. Meanwhile, the III Parachute Battalion again attempted to enter Rethimno and was again repulsed by the villagers and Police, this time with heavy casualties. The Germans found themselves pinned down, unable to advance or retreat. Artillery on Hill B began shelling this battalion.

The Stench of the Battlefield

The situation hung in the balance for the Australians and the Germans alike. While the Australians at Rethimno didn’t know it, the island defences further west were collapsing under relentless German pressure. The airfield at Maleme had been captured and Freyberg was busy coordinating counterattacks to try to push the Germans off the strategic landing strip. Meanwhile, the fighting around Heraklion at the far eastern end of Crete had ground down into a stalemate.

The German parachutists north of Hill B were also pinned down by heavy fire from the hill. They had no radio communications and had lost hundreds of men in the first day. An Arado AR 196 seaplane had attempted to bring a radio to the III battalion by landing close to the shore and deploying a rubber dinghy. The Australians on Hill B opened up and the crew were killed and the dinghy was sunk, along with the radio.

What the Germans didn’t know is that the Royal Navy had intercepted a German seaborne landing force heading to Crete. The German and Italian force was turned back after a brief skirmish. The paratroopers were on their own.

Major Kroh dug his troops in to Parivolia and the olive oil factory just east of the airfield. Colonel Campbell mounted multiple counterattacks on these positions over the next three days. He tried to get the two Matilda tanks working, but they broke down continuously. Both tanks seemed to be working fine on the morning of May 23rd, but as they set out to join another assault on the olive oil factory, they hit rocky terrain and bogged down. One lost its tracks in the boulders.

The Luftwaffe finally appeared in the sky on the 22nd and began providing effective air support, bombing the town of Rethimno and causing casualties on Hill B. There was an intense battle around Perivolia as the 2/11th Battalion attempted to push the Germans out of the village. They almost succeeded, but the Germans hung on. The arrival of Stuka dive bombers forced the Australians to retreat back to Hill B.

The Germans then launched an attack on Hill B the next day and strong air support helped them. But the Australians hung on. There was desperate fighting on the slopes of the hill throughout the day. Both sides were in grenade throwing range. The Luftwaffe attacked the hill with Bf-110 fighter bombers, but the Germans could not dislodge the Australians from the top. The attack faltered and the Germans retreated back to Perivolia at dusk.

Bodies were left out in the blazing Mediterranean sun for days. The corpses swelled up. Clouds of flies descended on the battlefield. Flocks of ravens pecked at the bodies. There were more than 400 German bodies rotting in front of the Australian positions and the smell of the battlefield became nearly unbearable. There were small unit clashes day and night as patrols ran into each other and snipers took potshots at exposed soldiers.

Captain Coombs of B Company, 2/8th Battalion, recalled the Australians always came out on top in these countless small unit actions.

When our patrols clashed we were always the victors. In these brushes we did not lose one man, but inflicted losses each time on the enemy. Our casualties were mainly from mortar fire,” he said.

Captain Coombs, B Company, 2/8th Battalion

Brigadier Campbell organized the entire defense of Rethimno with three old Greek telephones and a captured German phone.

Having no signal equipment whatever, I organised my signal platoon as a rifle subunit, keeping only a few men as runners. Fortunately, 6 Bty. 2/3rd Fd. Regt. had three telephones, and with one at HQ and one on each of Hills ‘A’ and ‘B’, we were able to maintain a party line as a means of lateral communication so everyone was kept in the picture. On 22nd May, when a Greek battalion got into position overlooking the olive oil factory, we used a captured German telephone to connect to that area.

Brigadier Ian Campbell

This went on for a week. On May 26th, Colonel Campbell launched a major attack on the olive oil factory. 2/1st Battalion joined up with the remains of the Greek 4th Battalion and they stormed the factory. There was hand-to-hand fighting, but the Germans were eventually overrun. The Australians took 100 prisoners and had cleared out the Germans near Hill A.

The Allies had a POW center set up near the town of Adele, not far from Rethimno, so Campbell had his prisoners sent over under guard. There was a field hospital there. Australian, British, Greek, and German doctors and medics worked side-by-side to help the wounded. They were low on medical supplies. Parachutes were ripped up and their silk used as bandages. The German prisoners, more than 500 of them in Adele, sat around smoking cigarettes. They didn’t have anyone guarding them.

Planning a visit to this battlefield?

Fill in the form below and a History Guild volunteer can provide you with advice and assistance to plan your trip.

The End is Close

Maleme airfield fell to the Germans on the same day Campbell seized the olive oil factory. Transport aircraft with mountain infantry were already beginning to land by the end of the day. Some of these carried light Panzer II tanks and Sd.Kfz.222 armored cars, providing heavy hitting power for the invaders. They also brought waves of motorcycle troops for fast movement.

The Germans began pushing the British and New Zealanders eastwards from Maleme, towards Rethimno. The Germans surrounded and captured several isolated British units during their advance and the defenses of the island began to fall apart. There was incessant bombing and strafing from the Luftwaffe, which had total air dominance over Crete. Freyberg gave the order to retreat towards the south coast on 28th May. The defenders were to be evacuated to Egypt.

The orders never reached Campbell and the Australians at Rethimno. Freyberg had sent a courier out with orders on the night of the 27th but he had been captured by a German patrol, so the Australians had no idea about the evacuation.

Interactive Map of the Battle for Rethimno

The Surrender

The men of the 16th and 19th Brigades were still dug in around the paratroopers of the I and III Battalions. They were shelling them from the heights of Hill B, but they were nearly out of ammunition and food by the 29th of May. The Germans endured this ordeal for over a week.

The advance units of the 141st Mountain Regiment and tanks from the 31st Panzer Regiment appeared to the west of Rethimno and quickly attacked picket lines to the south of Hill B. It took only a few hours for the advancing German 5th Mountain Division to surround and isolate Campbell and his men at Rethimno. Colonel Campbell realised it was over. He began negotiations for surrender at noon on May 31st and released all his German prisoners as a sign of goodwill. At 13:00, 934 Australians surrendered to the Germans. 52 of them managed to escape and made it to Egypt.

The Australians had suffered 286 casualties in 11 days of intense fighting at Rethimno. And although they had practically destroyed the Germans who had landed all around them, they ended up abandoned by the Allies in their hasty retreat from Crete.

The Germans suffered more losses in Operation Mercury then their entire operation in Yugoslavia and the Greek mainland combined. The paratroopers suffered almost 7,000 casualties, nearly half of whom were killed. At least 200 drowned when they missed their drop zones and landed in the sea. They also lost 200 Ju-52 transports, a loss they could not replace and which would have severe consequences on the entire Germany army in the coming Russian campaign when the Luftwaffe found itself unable to supply cut-off German units.

The German occupation of Crete was severe and brutal, with over 3,300 Cretan civilians executed by the Nazis. The Germans who occupied Crete lived out the war in relative comfort, and surrendered to the British at the end of the war in 1945.

The surviving units of the 6th Division were sent back to Australia in early 1942. The battalions were split up and assumed garrison duty along the northern coasts of Australia, while a new brigade was raised from militia units to replace the 19th, lost at Rethimno.

The Legacy of Ian Campbell

The Division was re-assembled in September 1942, and was sent to the New Guinea front. It would spend the rest of the war fighting the Japanese in New Guinea. The 6th was disbanded after two years in New Guinea and its men incorporated into other divisions across the Pacific theater.

Colonel Ian Ross Campbell survived his captivity in Germany and was awarded the Distinguished Service Order in 1946 and was made a Knight Commander of the Order of Phoenix by the Greek government. Many places around Rethimno are named after him today, including a street, a school, and a park.

He would go on to serve in the Korean War and would eventually lead the entire Australian army in the late 1950s. He passed away in 1997. The citizens of Crete sent a vial of earth from Rethimno to be buried with him.

‘Unsurpassed in the Annals of Australian Arms’

The Retimo sector was the only one in which Germans outnumbered the Empire troops. Their courage and spirit in the defence of Retimo is unsurpassed in the annals of Australian arms. For a loss of 120 dead and 182 wounded they had inflicted casualties totalling 700 killed and taken 500 prisoners. It was a superlative performance by the two depleted Australian battalions and their Greek comrades, darkened only by a destiny which decreed that the majority would have to spend the next four years as prisoners of war.

Peter Firkins, Australians in Nine Wars

Australian Units who Fought in the Battle

2/1st Australian Infantry Battalion

2/11th Australian Infantry Battalion

2/1st, 2/2nd and 2/3rd Australian Field Regiments and 2/1st Anti-Tank Regiment

Podcasts about Australians in the Mediterranean during WWII

Did my Relative Serve in these Battles?

Hundreds of thousands of Australians served in the Mediterranean during the Second World War. Some families know what their relative experienced during this often very important part of their life, but many do not. History Guild has a project where our volunteers research the service history of Australians who served in the Mediterranean. We have had a lot of interest in this service and have a large backlog of research to get through, so it currently closed to new entries.

We hope to re-open this service once we have finished our research on the current set of Australian servicemen and servicewomen.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.