Part of the Australian 6th Division, it was established on 13th October 1939 in Northam, Western Australia. This formation was unique within the 6th Division as it was the only infantry battalion raised outside New South Wales or Victoria, drawing the majority of its recruits from Western Australia. The unit adopted the brown over light blue color scheme of the 11th Battalion from World War I for its Unit Colour Patch, adding a gray border to differentiate it from its Militia counterpart.

Comprising about 900 personnel, the battalion was organised into four rifle companies, ‘A’ to ‘D’, each containing three platoons. Initial training was conducted in Northam before the unit moved to Greta, New South Wales, to join the 18th Brigade. In March, the battalion relocated back west before embarking from Fremantle to the Middle East.

In Egypt and Palestine, the 2/11th Battalion received further training before being reassigned to the 19th Brigade as part of a reorganization into three-battalion formations. The battalion’s combat debut came in January 1941 during the Battle of Bardia in Libya, followed by engagements in Tobruk, Derna, and Benghazi. This was followed by action in Greece, where the battalion fought in several successful delaying actions, including at Brallos Pass. The battalion fought tenaciously to prevent German paratroopers capturing the Rethimno airfield on Crete, holding out for over 10 days, only being forced to surrender when the Allied defenders further west were overcome.

After these devastating campaigns, the battalion was rebuilt in Palestine before joining the Allied forces in Syria post the Syria–Lebanon Campaign. The escalating threat from Japanese advances in the Pacific prompted the Australian government to recall its forces, including the 2/11th, back to Australia in early 1942. Upon return, the battalion was stationed in Western Australia for defensive operations before moving to Queensland in July 1943 as part of the 19th Brigade once more.

The battalion’s final major engagement was the Aitape–Wewak campaign in New Guinea, which began in January 1945. This operation involved patrolling and advancing through challenging terrain, including the Prince Alexander Mountains, and continued until the war’s end in August 1945. Following the conclusion of hostilities, the battalion’s personnel were demobilized and returned to Australia in stages, leading to the disbandment of the 2/11th on 7 December 1945.

Throughout the war, 2,939 men served with the 2/11th Battalion, which suffered 489 casualties, including 182 deaths. Members of the battalion were awarded numerous decorations for their service, including two Distinguished Service Orders, six Military Crosses, four Distinguished Conduct Medals, 20 Military Medals, and 66 Mentions in Despatches. Additionally, one member was appointed as an Officer of the Order of the British Empire, and three were made Members of the Order of the British Empire, marking the battalion’s distinguished contribution to the war effort.

The Men of the 2/11th Australian Infantry Battalion

Signalman Arthur Leggett

Arthur Leggett was a signalman in the 2/11th Australian Infantry Battalion, a veteran of the Greek Campaign, and a prisoner of war. He was born in Balgowlah in 1918. His father was a Great War veteran and a gas attack victim who had moved to the outskirts of Sydney in search of drier air, which was better for his damaged lungs. It was from here that Arthur had enlisted in the AIF at the very start of the war.

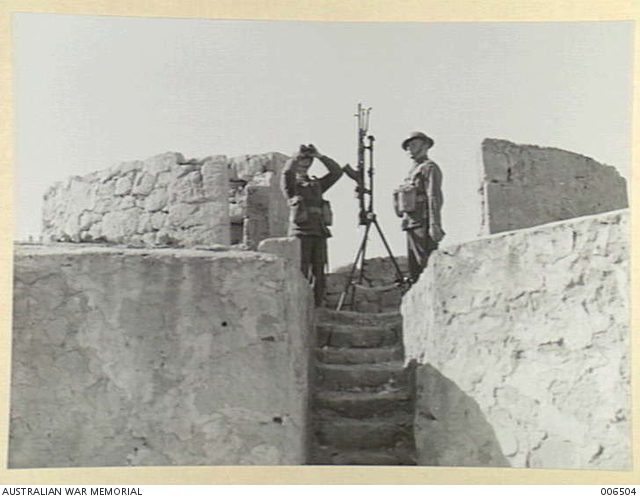

On his way to Colombo, and then the Middle East, Arthur was trained as a signalman, learning Morse code and flag signaling, among other skills. His first taste of combat came at Bardia, in January 1941. And after Tobruk, his unit went up to Greece in a convoy, but couldn’t land at Piraeus, the port of Athens, because an ammunition ship blew up there a couple of days ahead of them and destroyed the port facilities. Arthur’s battalion was taken ashore in little fishing boats and from there to Daphne. Seeing the Parthenon, even from afar, left a deep impression on Arthur, who remembered the image from books and magazines when he was younger.

It was not long before Arthur and his mates found themselves on the Greek and Yugoslav border, in what Arthur in hindsight understood was an impossible mission: to prevent numerically superior German troops from entering the country. “It was a different atmosphere entirely. We had been trained for desert warfare, which is dirty, which is flat, featureless. Here we were, everything was green, there were creeks going past, there were big rivers, there were mountains. It was an entirely different atmosphere to us in every way,” Arthur described the situation, adding: “We were bombed, we were strafed, all the way down through Greece. We had absolutely no aircraft support whatsoever. There was a Spitfire once, and we nearly shot it down. I can recollect that distinctly. We came back through Larisa, at night, which had been flattened by horrendous bombing raids during the course of the day.”

They gradually worked their way back down through Greece, and at Brallos Pass, they had to make a stand. Their task there was to hold the Germans up until nightfall. As a signaler, Arthur’s job was to relay commands from the higher headquarters to the front line. In his opinion, the troops were led by example, and he had nothing but praise both for his commanders and the troops. Air raids followed them from the Greek mainland to Crete, as they were attacked immediately upon disembarking at Souda Bay.

At Crete, Arthur and his battalion participated in one of the fiercest battles that took place on the island. Arthur recalled the situation: “Khania was the main airport, such as it was. We had an airstrip at Retimo, roughly halfway along the island. The German idea was that they were going to attack the main aerodrome and drop troops at this airstrip where we were and attack from the rear. We had our battalion, the [2/1st] Battalion, on the right flank, and we had a Greek regiment in the middle, and we had dug in the olive groves overlooking this airstrip, the area between our olive groves and hillocks overlooking this airstrip.”

Here, Australian troops fought valiantly and were able to resist German paratroopers for days, despite being low on ammunition, food, and even clothing. However, “when the [German] reinforcements came through, well, we had no hope in hell because we were just about out of ammunition, we were out of just about everything, food – everything,” Arthur recalled. The two Australian battalions were isolated pockets of resistance on an island already overrun by Germans. Even so, Arthur described that they felt like they were about to get out of it until the very moment they were captured.

He had no personal grudge against Germans, whom he held in regard: “After they became our guards, they were quite presentable, quite respectful, they respected you, and those that could speak English treated you accordingly. They were soldiers, we were soldiers. It was later on that we met up with a different type of German. But right then and there, no, they were young men who had been trained to fight, and they respected the enemy.” Nonetheless, conditions in POW camps were a struggle.

At first, Arthur and his mates were put in an overcrowded civilian prison, then later transferred to Munich in Germany where they would see the end of the war.

Arthur remembered vividly a particularly hard moment in captivity when he received the news of his father’s death: “I got a message the night before, in a letter, that my father had passed away. Well, the next day I was down in the dumps and the German asked me, ‘Mate? What’s wrong?’ I told him. They all came over to me, ‘What happened?’ I said, ‘He just died.’ They said, ‘How old was he?’ ‘Fifty-three.’ ‘That’s not old.’ ‘No, he was gassed in the First War on the German front.’ And one of them just walked away and he swore in German something terrible, and then he came back and he put his arm around me, I’ve never forgotten this, he put his arm around me, and, in German you can understand, he said, ‘Arthur, I am so sorry for you.’”

At the end of the war, Arthur was liberated by American troops. ANZAC POWs traveled to England where Arthur met his future wife, with whom he had two children, six grandchildren, and just as many great-grandchildren. In 2001, he was selected for the Australian contingent to go back to the 60th anniversaries in Greece and Crete, to represent Australia, which he found to be “a wonderful experience.”

Lieutenant Keith Dundas

Keith was 25 years old when he enlisted with the 2/11th Battalion in Kalgoorlie, in November 1939. Keith took part in the Battle of Bardia, where his unit arrived behind schedule and had to run to keep up with the artillery barrage. Later in the month they were fighting around Tobruk and Derna, and then Benghazi the following month.

He embarked for Greece along with the rest of the 2/11th Battalion in April 1941. The battalion fought at the Battle of Brallos Pass, a hectic, one-day battle on 24th April, 1941, fought 200 kilometres northwest of Athens. Keith’s C Company held the key terrain north of the village of Brallos, pinning down the German 55th Motorcycle Battalion that was advancing up the valley towards them, before breaking contact and withdrawing in good order once their job was done.

Visit the Brallos Pass battlefield

The 2/11th Battalion was evacuated from mainland Greece to Crete.

Keith was a platoon commander in the force defending Rethimno, in North-central Crete. He saw 11 days of continuous fighting in which the Australian forces successfully fought off the German paratroopers who had landed around Rethimno, attempting to capture the airfield. Read the full story of Lieutenant Keith Dundas’ war.

Podcasts about Australians in the Mediterranean during WWII

Did my Relative Serve in these Battles?

Hundreds of thousands of Australians served in the Mediterranean during the Second World War. Some families know what their relative experienced during this often very important part of their life, but many do not. History Guild has a project where our volunteers research the service history of Australians who served in the Mediterranean. We have had a lot of interest in this service and have a large backlog of research to get through, so it currently closed to new entries.

We hope to re-open this service once we have finished our research on the current set of Australian servicemen and servicewomen.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.