Part of the Australian 6th Division, these field artillery regiments were formed in 1939. They were drawn from the following regions:

2/1st Field Regiment from New South Wales

2/2nd Field Regiment from Victoria

2/3rd Field Regiment from New South Wales, Northern Territory, South Australia and Western Australia

2/5th Field Regiment from Queensland and Tasmania. However this became the 2/1st Anti-Tank Regiment in 1940.

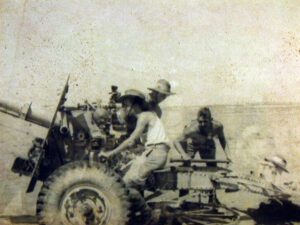

In 1940 the Field Regiments were equipped with 25-pounder artillery pieces and Morris gun tractors. They saw action supporting the 6th Divisions forces in the Western Desert before deploying to Greece as part of W force, where they saw much combat during the course of their fighting withdrawal down the length of Greece. They were forced to destroy their guns prior to leaving Greece, and took up the defence of Crete re-equipped with captured Italian and French pieces including 75 mm and 100 mm guns. The 2/3rd Field Regiment was assigned a coastal defence role at Georgiopolis, with a battery assigned to support the 2/1st Battalion and 2/11th Battalions defence of Rethimno.

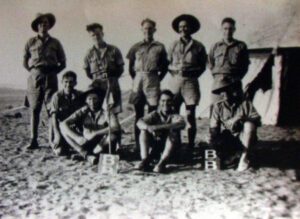

Men of the 2/1st, 2/2nd and 2/3rd Australian Field Regiments and 2/1st Anti-Tank Regiment

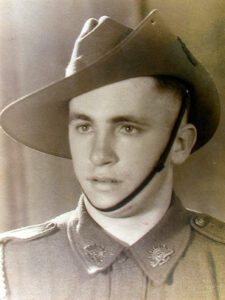

Bombardier Ross ‘Rosco’ Tattam, 2/1st Anti-Tank Regiment

Ross Tattam was one among very few people who can boast of enlisting for the Second World War together with his father. When Rosco’s father and uncles went to enlist for the Great War, he had a ruptured appendix while he was in the queue getting a medical examination, so he did not qualify. This time around, he had to claim he was 13 years younger, while his son claimed to be three years older, in order to be eligible to join the AIF.

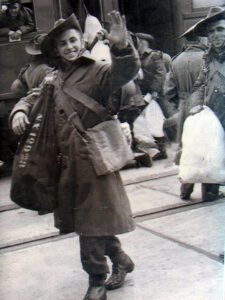

By the time Rosco shipped out onboard the Queen Mary, Italians had blocked the Red Sea, so their ship had to continue all the way to England, where they arrived nine weeks later. “The trip was terrific; we were passengers actually, since the army had chartered passenger space on the ship, and so we had steward service and everything else, which for an 18-year-old young bloke was pretty good going,” Rosco described. What they found in Britain was in sharp contrast; they arrived there for the Battle of Britain and had witnessed the destruction firsthand. Not long after, Rosco and 4000 of his comrades had sailed from Wales to the Middle East.

They arrived too late to bask in the glory of the victory at Bardia but just in time to join the ordeal in Greece. Rosco says that this is where he realised he was really in a war. He remembered Greek people being disappointed that all the allies could master was the force he was a member of, and there was a sense of impending doom from German forces that were capturing countries one by one. After Yugoslavia fell, it was on the Yugoslav-Greek border that Rosco saw combat for the first time: “This was an eye-opener, and we took a shellacking there. The first night of enemy activity, we lost practically a full battery, that’s a hundred and odd guys, and of the six in our poker group… two were killed, one was wounded and captured in action, and myself and one other got through and got well.”

What ensued was a retreat, orderly at first, but it soon turned to “every man for himself” Rosco remembered. During this ordeal, Rosco had contracted dysentery which slowed him down and made miss being evacuated together with his unit. “Incidentally, the family, the Greek family that took care of me there, the lady of the household was the niece of George of George’s Restaurant in Sydney where we used to eat fish every Friday night,” Rosco remembered. After he got back to Australia, he took a note from George’s niece to George himself and was a guest of honour at his restaurant henceforth. However, before he could go back to Australia, he had to get out of Greece, and his prospects were not looking good at the time. New Zealanders were in charge of evacuation at the last stages of it, and fortunately, Rosco was found by one of the officers and carried onboard. Dysentery, Rosco recalled, might have saved his life since the ship he would have boarded, if he was healthy and arrived in time, was sunk by the Germans. Rosco was evacuated straight to Alexandria and avoided the disaster at Crete.

Rosco continued as a dispatch rider in Syria after Greece and was seriously wounded in a hit-and-run accident. “I was lucky; there was a truck full of French Foreign Legionnaires from Senegal, big black men, and they got me and took me to a private French hospital where they had to threaten a doctor so he had to give me morphine or something. I had a compound fracture of the left leg and concussion and some other broken bones, and ultimately they got in touch with the authorities, and the Australians sent an ambulance up to pick me up,” Rosco described the incident. His leg could not heal in the war conditions, and even though he asked doctors to amputate it, he was sent to Australia and recovered enough to come back to the war and participate in the Papuan campaign.

After the war, Rosco loved to play rugby. He played for Wests as a scrum-half. He played rugby until he was 54. What he found particularly interesting was playing rugby in Japan after the war. It was at one of these “welcome home” parties after returning from Japan that he met his future wife. They had one child in Bombay, two in Calcutta, and two in Japan. Rosco was always involved in veteran activities and took pride in his service.

Captain Edward ‘Ted’ Hewit, 2/1st Field Regiment

Edward Hewit was born in Stockton but grew up in Toronto, NSW, as the son of a Boer War veteran. When the Second World War broke out, he was boarding in Newcastle where he was doing shift work at the steelworks. In October, he enlisted in the AIF. From November, he was training with his unit at Ingleburn, near Sydney, and in January sailed for the Middle East on the SS Orford.

For a short while, he was in an anti-aircraft regiment, combined with the 2/4th Battalion. When the Italians bombed the oil tanks in Haifa, he was manning the anti-aircraft guns, so this was his first taste of action. At Bardia, however, he was with his 2/1st Field Regiment, which was an artillery unit. They had just switched from eighteen-pounder guns, used in the First War, to the new British Twenty-five-pounders when the Battle of Bardia broke out.

Ted’s unit lost three men at Bardia, but he remembers it as the great victory it was. After Tobruk, the 2/1st Field Regiment moved out aboard a Dutch ship Pen Land, which later sunk. Their guns moved to Greece on a different ship, and it was a few days before the regiment was reunited with them.

Once in Greece Ted and his unit were constantly under German air attacks. He remembered the procedure demanded they abandon their trucks and equipment until the danger passed and then return. While hiding in an olive grove at one time, there would be no returning as a German dive bomber obliterated the truck, and with it, Ted’s gun and a watch he bought at Alexandria and meant to send to his sister. Fortunately, no one from his unit died in this attack, but during the retreat, their battery commander was captured by Germans, while one of their mates was killed on Kalamata beach before evacuating.

Ted remembered evacuation as a well-organised endeavor, which means his unit was among the first to get away. He went from Kalamata on the destroyer HMS Hero out to the ship, the Dilwara. Then he went from there in convoy to Alexandria. On their way there, they were bombed several times, but other than several near misses, nothing of note happened.

Of the entire campaign in Greece, Ted had to say: “Well, we were there for political reasons. We shouldn’t have been there for any other reason than that. Churchill had promised to help the Greeks and we went. I think strategically everyone knows that we shouldn’t have been there.” However, he said he has no resentment over the fact and would have done everything again given the opportunity. He thought Germans were a much tougher enemy than Italians: “Oh by a long, long way. Yes. We beat the Italians easily and the Germans beat us easily.” Ted was a bit saddened by the fact he later went to fight the Japanese instead of Germans.

In Greece, he was a bombardier, and in July 1941, he was promoted to a sergeant. While in the Middle East, he was sent to officer training and became a lieutenant. It was in this rank that he returned to Australia for the first time in 1942 and went to see his two sisters and his father, since his mother had sadly passed away in 1939.

He returned to the war in New Guinea the same year. Still in 1942, he contracted malaria, and while in hospital, met a nurse from 2/5th AGH (Australian General Hospital), who would become his wife after the war. Six weeks before the war ended, Ted was promoted to the rank of captain.

After the war, Ted got a metallurgy diploma at Newcastle Technical College and went to work as a supervisor at steel mills. He wrote a book about his experiences during the war and was proud to participate in ANZAC Day each year. Often his three daughters would come to support him during the march.

In 1949 Ted received a Military Cross at Government House in Sydney, alongside some of his mates. His former unit commander received an Order of the British Empire.

Sergeant Kenneth ‘Ken or Banksy’ Banks, 2/1st Anti-Tank Regiment

Kenneth Banks was a decorated member of the AIF who fought as a sergeant at Crete. When Ken enlisted for the Second World War, he was too young to be immediately sent overseas. Since he was unwilling to wait, the AIF decided it would be best to send him to training for Non-Commissioned Officers (NCO), which would take just the right amount of time for him to be of age. Ken was designated as a reinforcement for Malaya, but he asked to be sent to the Middle East instead. This is how he came to join the 2/1st Australian Infantry Battalion, which was fighting between Bardia and Tobruk in Libya at the time Ken came ashore in Egypt on board Queen Elizabeth.

At Tobruk, Ken had his first taste of combat and of command, as a sergeant in charge of his own squad. “The thing I can remember about it, we had the Black Watch with us, and they were Scottish and they had bagpipes. When the attack went over a certain time and they fired the very shots and we had to move forwards, the old forty and eighty traditional thing. I suppose the Italians thought, ‘Pretty, eh?’ all these things going up in the air. Next thing they knew there was a glint of sunlight on the bayonets coming through and the bagpipes, and of course there’s nothing more rousing than the bagpipes. It’d kill God if he turned up and looked nasty at it. No, that was my very first introduction, and the next thing we knew there was a big lot of white flags everywhere.”

Combat against Italians was a bit of a disappointment to Ken, as he humorously described the situation. “I was very disappointed there was no bayonet charges, you know, I thought I was going to be in this bayonet charge thing but there was none of that, the Italians could run faster than we could, so we couldn’t catch them, and when we caught them they had their hands up with the white flag and singing Ave Maria, and of course, you can’t bayonet a bloke doing that, can you?”

It was, however, much more serious than that as he found out soon when three of his close mates were killed by a bomb dropped from an airplane on the slit trench Ken was in. Ken himself survived thanks to his helmet, which he considered useless up to that point. He woke up in a hospital a few days later. While he was convalescing his battalion was badly beaten in Greece, losing a third of its manpower to Germans. Since there was no point in reinforcing them in Greece, Ken joined them on Crete.

He landed in Suda Bay, on the northwestern end of Crete, where ANZAC troops evacuated from Greece started to join them. “We realised that we were getting outflanked by these Germans. They were just in their thousands, you know. We didn’t have such big numbers because we lost so many in Greece, the division had. It was then that we realised that they were getting the better of us again, and so we had another evacuation on our hands then.” Suda Bay was overrun by that time so evacuation had to take place 40 miles away from there. “We put on a very good show, we were just holding them back all the time. I’d never been in a real war until then, this is where people were really dying – good, both sides, good soldiers from both sides were really dying.” Ken described the fiery retreat across the island. “We thought we’d done a good job, and we had, but when we got there, the last of them were still to go. We put up a big stand against the Germans and really got a big slaughtering there. So when they got the boat, they got off, our boat was there but only the mast was sticking out of the water and that was not much use to us.”

By this point, Ken and five of his mates were alone on Crete overrun by Germans, out of provisions and arms. They refused to surrender and with the help of the local population and resistance fighters managed to hide and find a bit of food for a few days until they found a boat: “It was about ten o’clock at night or something, and so we went aboard. The captain, and he had a crew of three, they were sound asleep, full of wine too, I think, they didn’t know what was going on, they thought they were having a bad dream. We told them – ‘This is a hijack, get up and go.’ And with the help of a revolver or two in the ribs, they got up and went pretty quick and got sober pretty quick. So we started the old motor up and she chugged away.”

They sailed to Turkey, and from there Ken managed to get back to the Middle East where he was briefly reunited with his brother, an AIF soldier who successfully evacuated from Greece. He also participated in the Papuan campaign and in the Allied occupation force in Japan after the war. He got married immediately upon returning to Australia and had two sons.

Sergeant Michael ‘Mick’ Lardelli, 2/1st Field Regiment

Michael Lardelli was born on 12th February 1922, and coincidentally, it was 12th February 1940 when he first set foot at El Kantara in the Suez Canal. According to the papers he gave the AIF in October, he was supposed to be turning 21 (the minimum prescribed age for service), however, he was only 18. In the desert, he did a lot of training on 4.5-inch howitzers and was appointed a gun layer in the gun crew. A crew usually consisted of six men, as Mick explained: “1 sergeant and the No. 2 were bombardiers, and the No. 3 was the gun layer, and 4, 5, and 6 were ammunition Nos.”

Mick’s gun crew was battle-tested at Bardia in January 1941. They were active throughout the battle, which he described as old-fashioned, with artillery exchanging barrages and infantry charging trenches and walls. What stuck most in his memory were the opening moments of the battle: “a whole ring of fire just leapt out of the guns, you know 140-odd guns lined around Bardia, and behind us, of course, were the medium guns, but just that the sound and the flashes of the guns were fascinating.”

A couple of months later, they arrived at Piraeus in Greece. Mick described their arrival: “We got off the ship and went out just from Piraeus into an olive grove, and that day the Germans bombed hell out of Piraeus and just about flattened them because they blew up an ammunition ship in the port, but anyhow, we had our guns off the ships by that time.” In fact, in the next few days, they were on trains heading to the border with Yugoslavia, which was about to surrender to the Germans.

The confrontation between ANZAC and German forces took place at the Battle of Tempe Gorge on 18 April 1941. Mick’s 2/1st Field Regiment came from Larissa to delay German progress into Greece, since preventing it would have been impossible with the manpower and firepower present. Mick described the aftermath: “We’d pick up our guns and go back behind like I’d called it a leapfrog action; we just keep leapfrogging all the way back down through Greece, defending in the main passes but continually being bombed by Stukas, mainly. Surprisingly enough, we didn’t have many casualties; no one was killed outright in those bombings, but mainly broken bones from flying rock, you know, and from the bombing.”

Following the retreat, Mick’s unit was supposed to be evacuated from Argos Bay; however, “all the ships had been sunk and were just sitting on the bottom; apparently it wasn’t very deep.” Thus, an alternative evacuation point was picked; however, only 92 out of 400 managed to get aboard the destroyer that took them to their next vessel, Mick remembered. Two troop ships came to gather the men, Costa Rica and Dilwarra. “They had 6000 of us on the Dilwarra; you could sit down or stand up, but there wasn’t room to lie down,” Mick remembered. The following morning things got significantly more dramatic: “as soon as daylight broke, the Stukas got stuck into us again; they sank the Costa Rica, and they ran a destroyer up each side of her, and we could see this happening, and they took those boys into Crete. We mounted on the deck of that ship of our ship 132 machine guns, which meant we could keep the Stukas up; you’d just send up a hail of bullets, and though we had a lot of near misses and the boat was leaking pretty badly, we survived the Stukas by that time the next day we’d run out of range of them and so the Dorniers the longer-range bombers you see came and gave us a little bit of a tickle up then but we actually got back to Alexandria.”

After the Greek campaign, Mick participated in both the Syrian and Papuan theaters and was discharged in 1945, after the hostilities ceased, at the rank of sergeant. In 1946, he bought a farm and got married. He spent over 30 years in local politics and served several times as the Mayor for the city of Ryde.

Podcasts about Australians in the Mediterranean during WWII

Did my Relative Serve in these Battles?

Hundreds of thousands of Australians served in the Mediterranean during the Second World War. Some families know what their relative experienced during this often very important part of their life, but many do not. If you have a relative who served in the Australian armed forces during WWII and would like to know if they served in the Mediterranean please fill in the form below.

History Guild volunteers will research your relative’s service history and let you know what they find. As this is a free service provided by volunteers the timeframe may vary.

The text of this article was commissioned by History Guild as part of our work to improve historical literacy. If you would like to reproduce it please get in touch via this form.