Reading time: 8 minutes

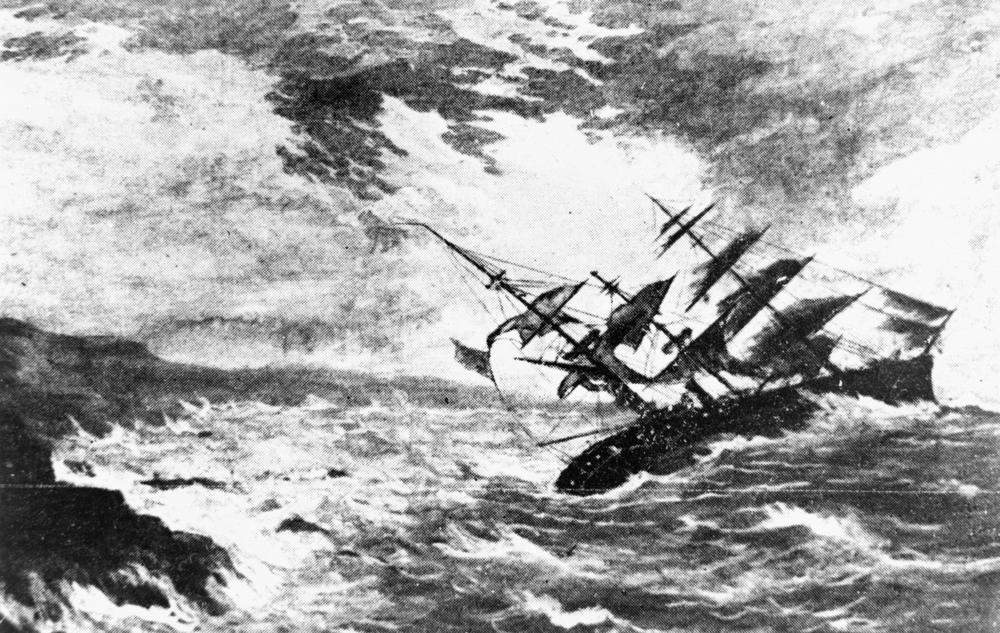

With howling westerly winds and in freezing rain, the unforgiving waves push ships closer to the treacherous rocks of the merciless Cornish coastline. The crew has travelled miles with precious cargo, desperately trying to right their course with no modern navigation. In an attempt to save the vessel and themselves, they begin to throw goods overboard.

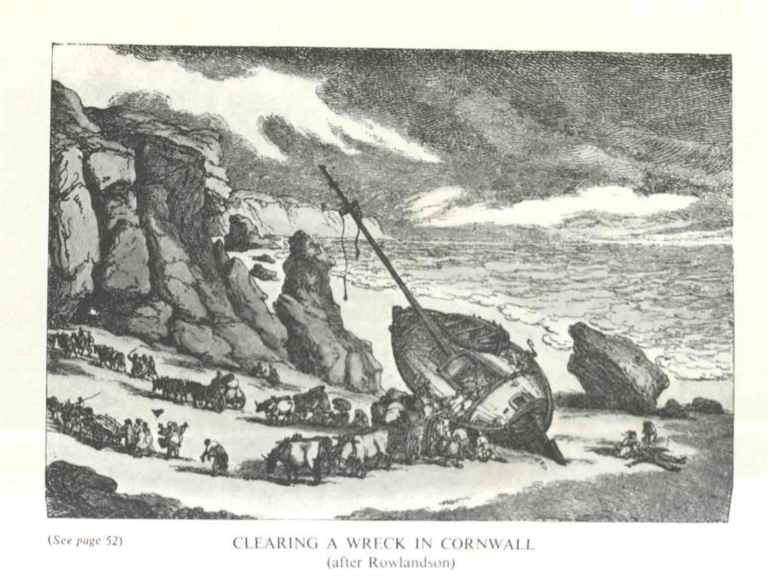

Countless lives, ships and cargo have been lost along the Cornish coastline. Wrecking – a well-known yet perhaps mythical aspect of Cornish history – is often associated with the deliberate act of luring ships to shore by poor lower-class tenants. In comparison, the term ‘wrecker’ relates more closely to residents who retrieved the goods washed ashore, especially as the finder could claim one-half of their value as salvage. It was this lucrative right to the wrecked goods that often led to zealous legal disputes between neighbouring landowners of coastal manors.

This is a topic with many facets, too broad to cover in their entirety, but this blog hopes to provide an interesting insight into the ‘right of wreck’ along parts of the Cornish coast.

By Kate Rose.

The ancient right of wreck

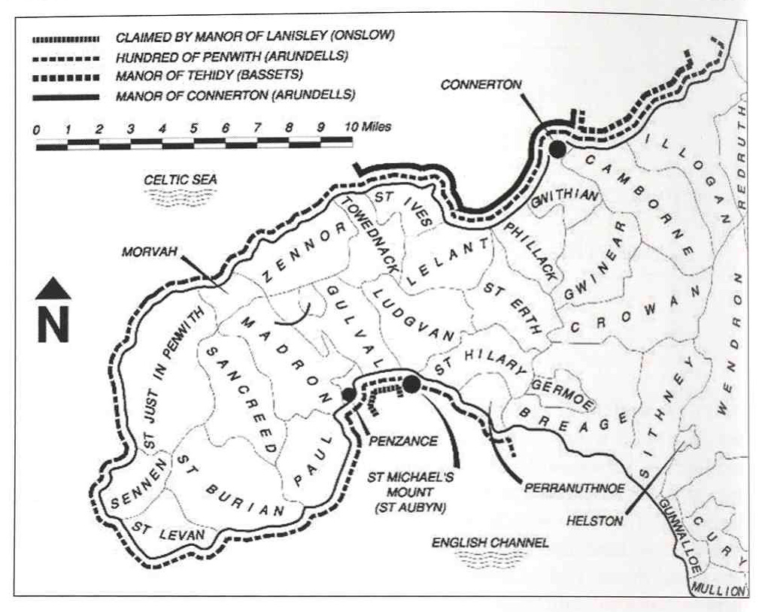

The right of wreck could be considered one of the earliest maritime franchises granted by the Crown to local landowners holding manors or hundreds. Hundreds were larger units of land in which manors could be located. All the hundreds in Cornwall originally belonged to the Duchy, except the Hundred of Penwith. The right of wreck franchise would entitle landowners to a combination of the flotsam, jetsam and ligan but did not necessarily include ownership of the land or sea. At any one time, different landowners could hold different rights along the same part of the coast … what could possibly go wrong!

Wrecking Definitions

Flotsam – goods that are floating on the surface of the water as the result of a wreck or accident.

Jetsam – any cargo that is intentionally discarded from a ship, most often to lighten the ship’s load.

Flotsam may be claimed by the original owner, whereas jetsam may be claimed as property of whoever discovers it.

Ligan or Lagan – goods cast overboard and heavy enough to sink to the ocean floor, but linked to a floating marker, such as a buoy or cork, so that they can be found again by the person who marked the item. This buoy constitutes sufficient grounds for laying claim to the goods, therefore ligan must be returned to the rightful owner.

Disputing landowners

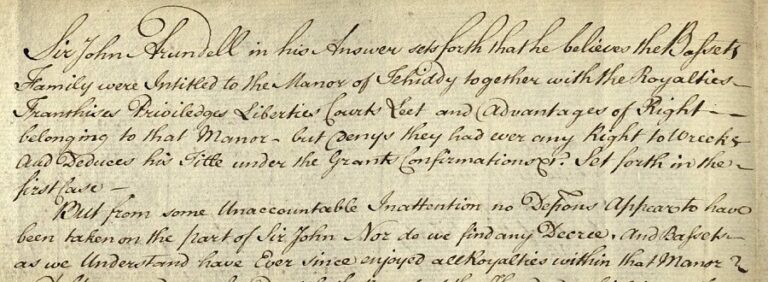

Wreck records provide an intriguing insight into the complicated and delicate relationship of neighbouring manorial lords. The manor of Tehidy (owned by The Bassets) sat within the Hundred of Penwith (held by the Arundell family). Perhaps among the shrewdest and wealthiest lords in Cornwall during 18th century, the Bassets frequently disputed the right to wreck of the Arundell family and fought ardently to prove their entitlement to wrecks within the manor of Tehidy. Surviving archive material documents the two families disputing their rights for nearly 100 years, often citing a lack of decree to either’s claims. It seems due to a lack of evidence that the families’ last wreck encounter was thrown out of court and the Bassets enjoyed all royalties within the manor ever since.

The Arundells were often involved in further disputes with other landowners, the details of which can be found on the Kresen Kernow website.

A great fish and Civil War dispute

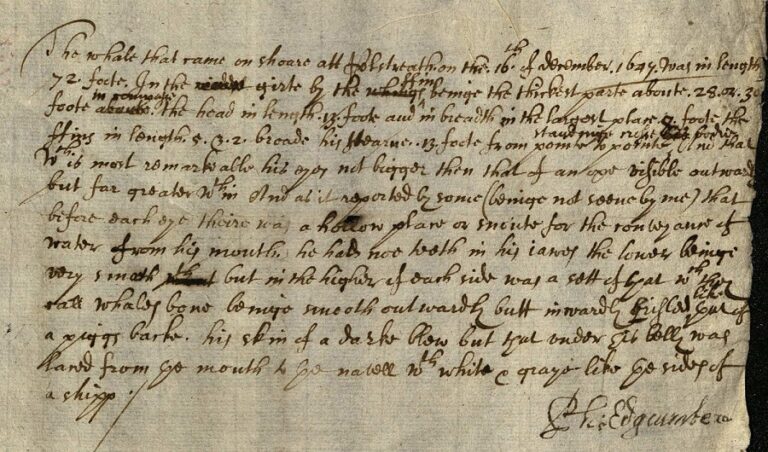

Amongst the turmoil of the Civil War, a great fish was washed ashore near Mevagissey, within the manor of Bodrugan. A series of letters from Richard Edgcumbe at Bodrugan to his brother Colonel Piers Edgcumbe documents the legal dispute with the admiralty over the great fish. The great fish (whale) is described in vivid detail as ‘so odious to the smell as that I could not endure to come near it’. Its description includes a length of 72 feet, girth by fins 28-30 feet, its head 13 by 8 feet, with fins 5 by 3 by 2 feet, and its eyes no bigger than an ox’s.

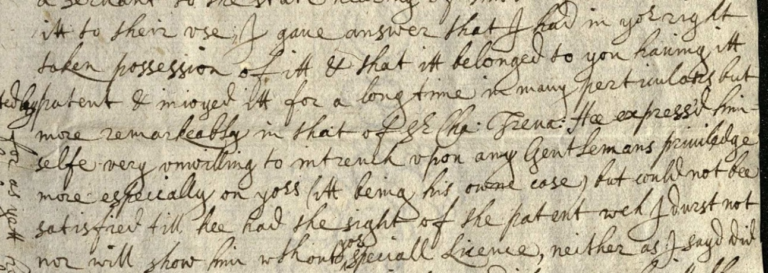

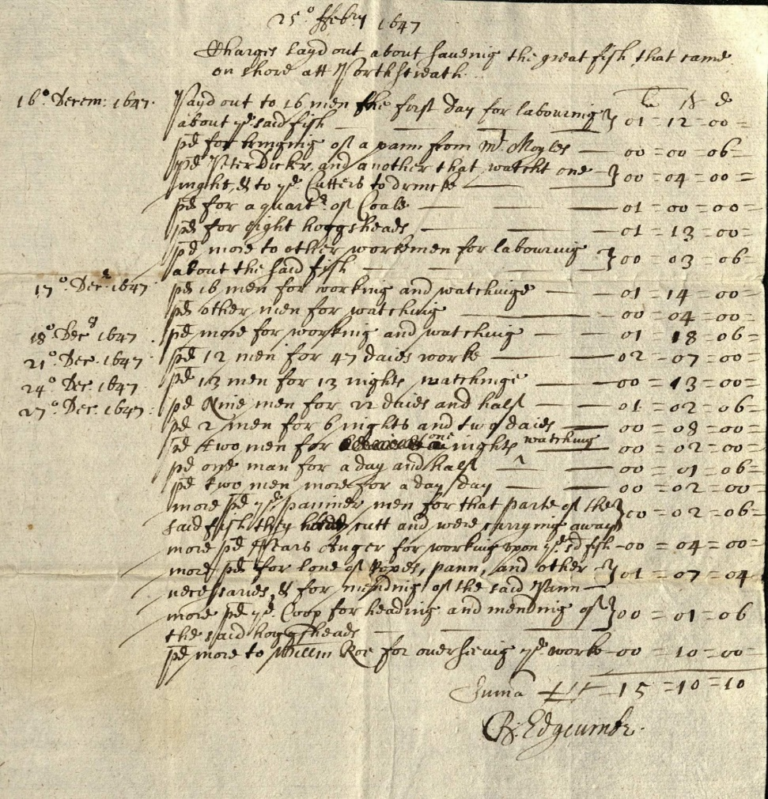

Richard first writes to his brother on 16 December 1647, notifying him that a whale has been cast ashore and, as he has the title and privilege of wrecks, he seized it on his behalf, even though there is already strong opposition from the Admiralty. Four days later, he writes that John St Aubyn, Vice Admiral for Cornwall, has come to seize the whale and states he ‘could not be satisfied till he had the sight of the patent’. One does wonder if this was merely just a case of right of wreck or, as the Edgcumbes were staunch Royalists and Aubyn was a Colonel in the Parliamentary army, perhaps this whale signified something more.

With the aid of legal counsel, the brothers made a defence, outlining the total cost of the endeavour while refuting the claim that it was a whale (more of a great fish) and underlining their right of wreck. It seems that the onset of the Second Civil War may have saved the Edgcumbes as the Admiralty’s attention turned elsewhere and we hear nothing more of the case except a set of jaw bones sit at Cotehele, although their origin is unknown.

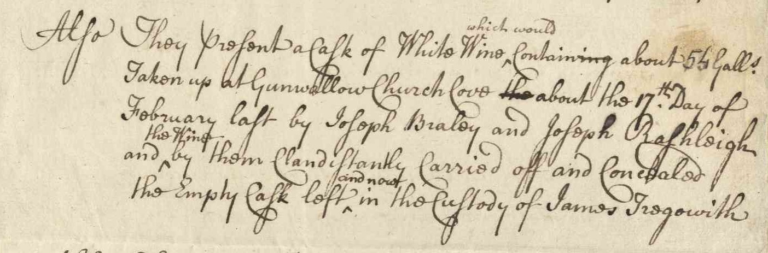

A fine for clandestine wine

Presentments are formal statements or evidence provided to a manorial court and these documents provide an insight into the relationships between the lord and their tenants. Walking a fine line between legal and illegal wrecking, lords of the manor held great sway over their tenants, who usually informed manor officials of a wreck. The tenant who found the wreck would receive half the goods and the other half would go to the lord. The amounts collected from wrecks were highly unpredictable but, when large vessels were lost, the profits could be spectacular.

Two such tenants on the manor of Winnianton perhaps decided that the risk of a fine from the lord was worth ‘clandestinely’ carrying off about 54 gallons of wine from Gunwalloe church cove, with the empty cask being presentment at court. In cases of such misdemeanours, the resident lord of the manor handed out fines as punishment.

An unexpected elephant’s tusk

Wreck presentment records can also provide us with a historical snapshot of the trade in goods. Ships travelled great distances, bringing with them cloth, spices, tea, hogsheads of wine, rum, anchors of brandy, sugar, precious jewels and ivory. An interesting wreck find, recorded as being found ashore within the manor of Methleigh, was an elephant’s ‘tooth’ (tusk). The full document, written by the steward of the manor, is dated 31 October 1765 and mentions a French ship thrown ashore under the lands of Trequean, near Rinsey, within the manor. The commercial trade in ivory for piano keys, jewellery, ornaments and works of art was nearing its peak at this time.

Right of wreck records provide us with a fascinating insight into life on coastal manors, including the relationships between neighbouring lords and their tenants. Localised brushes with manorial law provide us with wider historical insight into maritime and trading history. This blog has only just touched on the topic and if you would like to know more about wreck records and the Manorial Document Project for Cornwall, please contact Kresen Kernow – A home for Cornwall’s archives. You can also learn more about the Manorial Document Register. And finally, if you find yourself walking along the coast and stumble across a piece of sea glass, a buoy, some driftwood, or pick up pieces of plastic washed in with the tide, you might just be a modern-day wrecker!

This article was originally published in The National Archives.

Articles you may also be interested in

Dunkirk: how British newspapers helped to turn defeat into a miracle

Reading time: 6 minutes.

with the 1963 film of that name starring Steve McQueen, reffering to, of course, a mass escape by Allied prisoners during the second world war. But this title might more appropriately be applied to the rescue of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) from Dunkirk between May 27 and June 4 1940.

Losing the war in an afternoon: Jutland 1916

1916 was the pivotal year in the First World War. In February German forces attacked the French at Verdun, while 1 July will mark the anniversary of the Anglo-French offensive on the Somme.

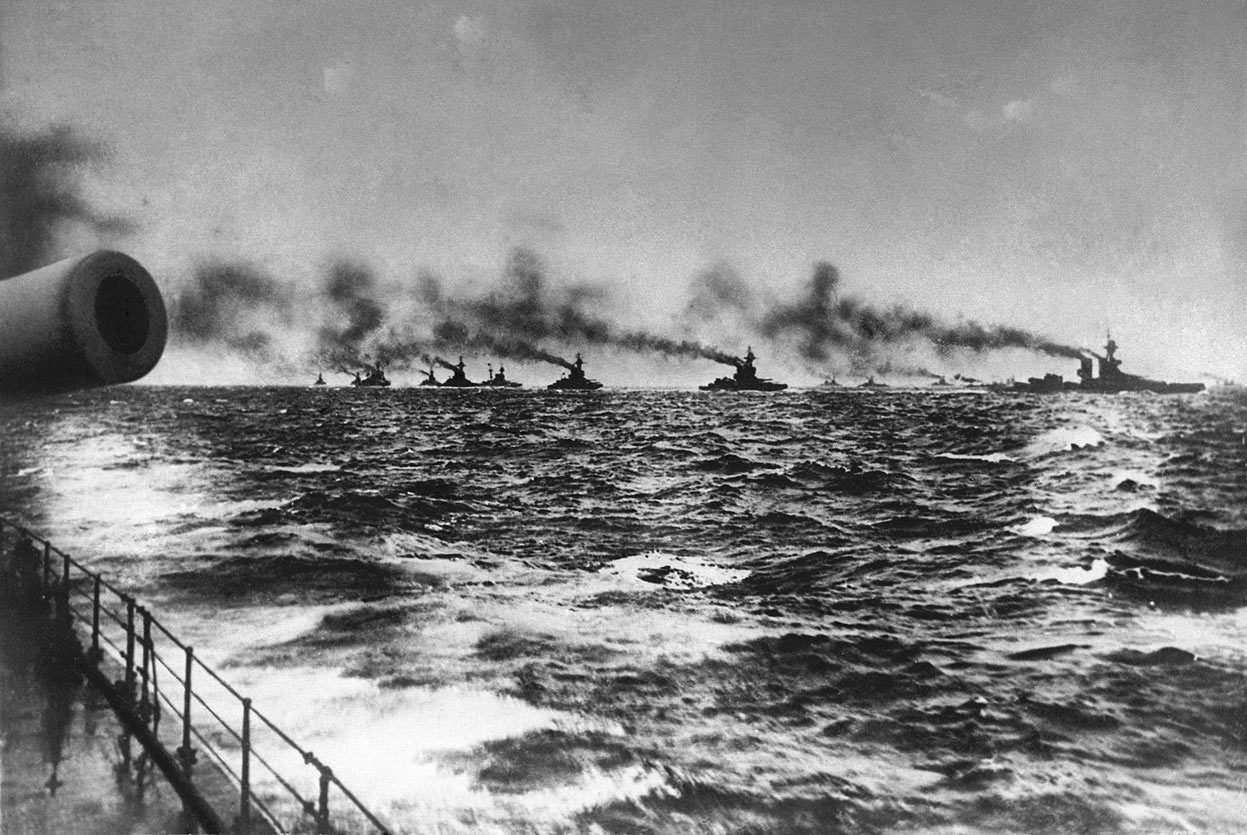

HMS Terror wreck found – but what happened to her doomed crew? Here’s the science

It remains one of history’s best-known naval tragedies – and mysteries. The loss of all 129 men of the 1845 Royal Navy expedition led by Captain Sir John Franklin to navigate a north-west passage through the Arctic remains an enigma. The only informative document to be recovered from the expedition was a single page that reported initial […]

This article was first published by The National Archives. It is reproduced in accordance with the Open Government Licence v3.0.